Throughout 2021, in addition to the unprecedentedly high level of political prosecution, state authorities have continuously monitored and harassed citizens unlawfully without warrants. This has occurred so much to the point that it almost became “normal”. And, no one has been seriously keeping authorities’ use of power in check.

This behavior by state officers was first identified after the 2014 coup d’état led by the NCPO, where military personnel was dispatched to invade people’s houses or force them into a “readjustment program” at a military barrack. It was one of the operations the coup-makers used to control political expression. Despite after the 2019 election, the operation endured, but was instead transferred to police force.

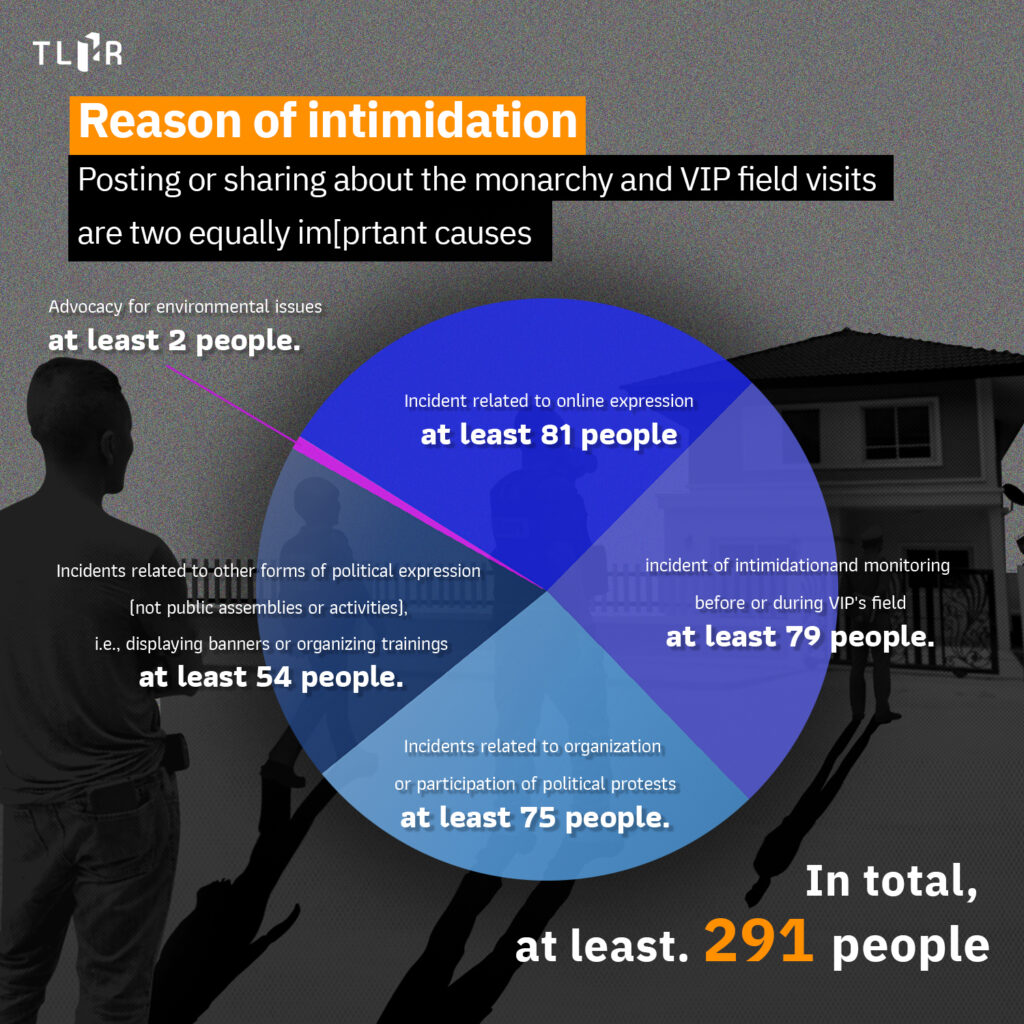

According to the statistics compiled by the TLHR throughout the year, at least 291 activists and citizens, 39 of whom concerned youths under 18 years old, received house visits or were summoned for talks by authorities. These numbers do not include cases where authorities went to deliver summon warrants or make an arrest as part of a prosecution. (Data as of 25 December 2021)

Geographically speaking, the intimidation incidents took place to at least 126 people in the Northeast, 86 people in the Central, 63 people in the North, and 16 people in the South.

The figures only represent what has come to TLHR’s knowledge. It is assumed that the number of the incidents of intimidation that have actually occurred all over the country throughout the year would have been far greater. According to sources, authorities were reported to have told the affected citizens and activists that there were many other people to monitor in the said province. In some cases, the authorities also revealed the names of several dozens of people whom they were ordered to follow. Furthermore, some activists were monitored multiple times over the course of a year. As a result, it was proven difficult to follow and clearly grasp the whole picture of the intimidation situation.

Reasons of intimidation: Posting or sharing about the monarchy and VIP field visits are two equally important causes.

The broad reasons of state intimidation, as far as the TLHR is aware, are as follows:

1. Incidents related to online expression: at least 81 people. Most concern the sharing of opinions about the monarchy.

2. Incidents of intimidation and monitoring before or during VIPs’ field visit: at least 79 people. “VIPs” refer to royal family members and government leaders.

3. Incidents related to organization or participation of political protests: at least 75 people.

4. Incidents related to other forms of political expression (not public assemblies or activities), i.e., displaying banners or organizing trainings: at least 54 people.

5. Advocacy for environmental issues: at least 2 people.

Constant surveillance and intimidation of people expressing opinions about the monarchy.

A notable trend in the state monitoring and intimidation most commonly found throughout the year was the monitoring of ordinary citizens who posted, shared, or commented about the monarchy. This is a phenomenon that has begun around 2019, when the use of Section 112 was suspended. Even towards the end of 2020 when this charge was revived, this pattern of state intimidation carried on, where people expressing opinions about the monarchy online were coerced to delete the content, have profiles made, sign a memorandum, or give access to data without informing the charges,

A good portion of intimidation, at least 28 instances to be exact, in 2021 was originated from the posts shared from the “KTUK – Kon Thai UK” Facebook Page. While all the post content revolved around the monarchy, most people just shared it from the page without attaching their personal opinions. This reflects the state’s tight grip over the said page. Some users who shared posts from the account ‘Pavin Chachavalpongpun’ or ‘Somsak Jeamteerasakul’ faced backlash, too.

Many instances of intimidation were unclear as to from what posts they stemmed from. The authorities simply claimed that content posted or shared was related to the monarchy or fell within the scope of Section 112. In some cases, authorities printed out several posts that were shared to show at once.

Almost all cases of intimidation involved ordinary citizen Facebook or Twitter users, and not political activists. Many of them were not made public or did not reveal the situation to the public. Furthermore, the intimidation widely spread to different parts of the country.

Cases concerning Kon Thai UK posts that were picked up by the media include: A 22-year-old man in Krathum Baen District, Samut Sakhon Province who was approached by police and forced to fill out personal data and sign the “Attitude Adjustment Report” and a memorandum agreeing not to share “inappropriate and unsuitable” statements, three citizens and students in Khon Kaen Province who were visited by police at their houses threatening them with lawsuits and forcing them to delete the posts, as well as citizens in Chiang Rai, students in Maha Sarakham, students in Surin, students from Udon Thani Rajabhat University, a man from Lopburi, two citizens in Surin, or a man in Nakhon Ratchasima who have all faced similar intimidation and pressure by police to delete posts shared from the Facebook page.

Other cases involving shared posts: a company employee in Ayutthaya was monitored for sharing several posts from the account of “Somsak” and “Pavin” and ordered to stop sharing monarchy-insulting content as well as threatened with prosecution. A fitness trainer in Roi Et was monitored for sharing posts from the Free Youth page. A High Voc. Cert. student from Udon Thani shared a picture of a person flashing the three-finger salute in front of the portrait of King Rama X and was ordered to delete it and warned not to post or share about the monarchy again.

Many cases of intimidation concern just high school students: two students in Phitsanulok were approached by the police to ask the parents to order them to delete the posts they shared about the monarchy. A high school student in a province in Central Thailand received a family visit by two plain-clothed police officers asking him/her to delete the Facebook post criticizing the monarchy. Or a Grade 9 student in Surin was summoned to meet the school principal to persuade him/her to stop sharing news about the politics and monarchy.

Other interesting cases: police summoned a citizen in a province in Central Thailand to the police station without warrant to verify the identity of her Facebook friend and asked why she liked an image with caption “Abolish 112” posted by that Facebook user. A private company employee received visits by the police two days in a row allegedly to find the owner of a Twitter account that tweeted a satirical content about getting paid to stand in the cinema (during the royal anthem).

Monitoring and intimidation before and during field visits of Prayuth and royal family members.

Another noteworthy and common reason of intimidation of activists or citizens is that occurring before and during Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha’s visits to various provinces.

Activists or citizens in different provinces were monitored because they had backgrounds in political participation. Authorities usually paid them a visit to their houses, asked for a meeting, inquired about their plan, or prohibited them from doing any political activities. They might even keep watch in front of their houses or followed them in a car to prevent them from going anywhere during a government leader’s visit. Examples include activists and citizens in Ubon Ratchathani in October and in Udon Thani in the beginning of December before Gen Prayuth’s arrival.

The intimidation in this nature also extended to neighboring provinces. For example, prior to Gen Prayuth’s visit to Krabi and Trang in November, it was reported that students and activists in several Southern provinces were monitored as well.

Meanwhile, visits of royal family members to various provinces also triggered a monitoring operation of people in the “watchlist” of the respective local government. The Thai Lawyers for Human Rights found that such incident had begun since 2020 when the King and the Queen travelled to perform royal duties outside of Bangkok and the local police moved to monitor the movement of students, professors, activists, artists, or people with background of political activities in that province or including the neighboring provinces too. Cases were present in Chiang Mai, Udon Thani, Ubon Ratchathani, and Pattani.

In 2021, the trend continued, and also extended to the visits of other members in the royal family, such as Princess Sirindhorn and Princess Bajrakitiyabha.

Important events that were reported are: the monitoring of politically active scholars and students in Phitsanulok and Chiang Mai in March 2020 before the King and Queen’s royal duties, and the monitoring of people who used to join political assemblies in Chai Nat before a royal visit to Supanburi at the end of March.

Students and environment activists in Sakon Nakhon and Roi Et were monitored before Princess Sirindhorn’s visit in May and before her visit in Khon Kaen, Buriram, and Surin in June. The same was true for Nakhon Ratchasima, Ubon Ratchathani, and Chiang Mai before Princess Sirindhorn’s visit towards the end of the year as well. In Bangkok, the monitoring and surveillance of scholars or artists by authorities before royal ceremonies were reported.

In general, the affected people in different provinces were not even aware of if, what, and how the royal visits would take place. Neither did they plan to organize any political activities. The authorities’ operations to monitor and intimidate people in this manner are likely to affect people’s feelings towards the monarchy, too.

The monitoring and intimidation of citizens as a result of having organized or participated in political assemblies.

Monitoring groups of students or activists who organized political activities in various locations to intimidate them or restrain them is considered another important tactic authorities used to stifle political expression. The organizers of assemblies or activities often became “targets” of the monitoring both before and after the activity to collect information or give warnings.

In 2021, authorities attempted to restrict a number of activities. In case of the “Buriram people reclaim democracy” activity organized by the “Buriram No Dictatorship” group in April, for example, the police paid visits to the houses of the young organizers. An activist in Kanchanaburi who planned to organize a protest activity in front of the house of an MP who had casted a confidence vote for Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha was kept watch by authorities in front of his house. Another activist was visited by police officers who also talked to his family, which led him to call off the activity.

In the duration of the car mob activities in various provinces, authorities also approached groups of organizers to acquire information, prohibit the activity, as well as threaten them with lawsuits. For example, an activist leader in Udon Thani was visited by police at his house four times and several activist received a phone call from the police to obtain information. In Phon Thong District, Roi Et, an organizer was summoned for a talk at the police station twice and was threatened with lawsuit with charge under the Emergency Decree if he held an activity. In Kanchanaburi, a car mob organizer received a house visit by a total of more than 30 police, military, and security officers and a legal threat. In Kalasin, police scheduled a meeting with car mob organizers asking them to postpone the activity on 12 August. In Phitsanulok, police summoned car mob organizers for a talk at a coffee shop and threatened them with lawsuit, which led them to cancel the event. In case of the car mob activity by the Thonburi Citizens group, the page admin was visited by seven police officers at his house and was threatened to call off the activity, as well as was kept under surveillance to prevent him from going out.

Commemorative events on politically important days were also not without state monitoring and intimidation. For instance, a student in Kalasin was visited by a stranger man at home to inquire about his personal information following the 24 June Commemoration Activity. A participant who was holding a banner at the 6 October Commemoration Activity in Kalasin was visited by security sector personnel to discourage him. Three activists in Chaiyaphum were visited by the police at their houses to ask about their information and warn against the content of the activity following the 14 October Commemoration Activity.

Moreover, police monitored citizens in various provinces during assemblies in Bangkok to check whether they were joining the activities. For example, in February, a Grade 12 student in Chiang Rai was visited by the police at the school for allegedly being one of the people on the “watchlist” who would likely attend a protest in Bangkok. Several other students experienced similar situation around the same time. A merchant in Nonthaburi received no fewer than 10 police visits at his residence and factory to warm him against joining protests, after he had been accused and detained from the 11 August protest.

Police also regularly followed, surveilled, or approached the parents of activists who played a role in organizing protests. For example, Rung Panusaya were visited or spied by the police at her house multiple times. Pongsatorn Tancharoen, a member of the MSU Democracy Front and Katanyu Muenkamrueang, members of Talufah group, also received visits by police officers in their hometowns claiming that they were on the blacklist.

The monitoring of people as a result of non-political or non-public activities/assemblies.

The monitoring by state authorities also took place with other forms of political expression that was not a public assembly, such as after hanging banners containing political statements or organizing trainings in various topics.

Since the beginning of the year, police approached the parents of a 15-year-old youth in Roi Et after banners with text “Abolish 112” were hung on flyovers in the province. In Petchabun, around eight police officers visited the house of a student after a banner with text “Arrest Children, Worship Dogs, Press 112 Charge” was found on a flyover in the area.

Similarly, two members of the People’s Party of Bueng Kan group received a house visit by the police after the banner “Abolish 112” appeared on a flyover in the province. In Surin, police tracked down the people responsible for fixing banners with anti-Prayuth texts on traffic signs. In Nonthaburi, police invaded and searched the apartment of the activists of the Nontaburi New Generation Network to check for political banners.

Early in the year, the “Ratsadon On Tour” camp was organized for school students in Phu Khiao District, Chaiyaphum to learn about social issues. However, the parents of at least four students were visited by police officers to dissuade them from letting their children join the camp. The parents were also approached by administrative teachers of the school.

In Pattaya, Chonburi, police took turns to monitor the camp on welfare state by observing and acquiring information about the activity for many consecutive days. Also in Pattaya, after a group went around to attach banners with text “Failing State, Dying People” and hang an effigy to protest the Covid-19 management policy, its members were visited by officers at their houses as well as had the pictures of their movement taken in front of the group’s residence.

In addition, authorities employed a “blanket” intimidation approach in order to identify the people who took part in the political activities. For instance, officers invaded the houses of three members of the Korat Movement group to investigate the royal portrait burning incident in the province; however, none of them said they knew anything about it.

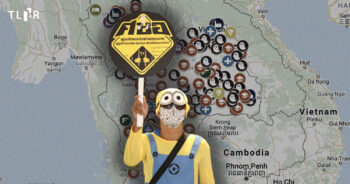

At least 377 Facebook and Twitter users received threat messages from THCCV.

In parallel to state monitoring and intimidation, 2021 also saw a situation where “a people’s group” called the “Thailand Help Center for Cyberbullying Victims (THCCV)”, also self-called the “Minion Troop”, used dozens of fake accounts to send a compiled set of personal data to owner’s Facebook or Twitter account via direct messages and threaten him/her with Section 112 lawsuits.

The described situation began in the beginning of June 2020. Until the end of the year, it was still reported that people continuously received such threats. Throughout the second half of the year, the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights received complaints from at least 377 citizens about the intimidation in that manner. (Data as of 25 December 2020)

There have also been some reports of citizens experiencing more than just threats. In certain cases, the THCCV also forwarded the data of the users’ social media posts to their workplace. As a result, some people were pressured to resign, such as in the case of a male factory workers in Samut Prakan.

It is speculated that the number of complaints merely represents a fraction of people who received such treatment. The actual number is expected to be several thousands. By the end of 2021, there were still no reports of people who actually received an official summon warrant from the police. Thus, we will have to continue to keep an eye on the development of this situation as well as the possible actions by state authorities next year.