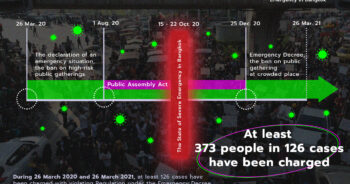

The prosecution of the protestors and politically active citizens soared rapidly in the past month as a result of series of mass arrest following political activities. Charges were also pressed on people that had never previously been prosecuted, which raised this month’s statistics of people targeted for their political involvement.

In overview, the TLHR has observed that at least 581 people in 268 cases have already been accused for their participation in protests or political expression in the course of just over eight months since the “Free Youth” rally on 18 July 2020 until 31 March 2021.

When compared to the figures as of the end of February 2021, 61 additional cases involving 199 citizens took place in March alone (see the summary of cases in February).

The cases can be divided according to charges, as follows:

- “Lèse-majesté” or the Section 112 of the Penal Code: 82 people in 74 cases.

- “Sedition” in the Section 116 of the Penal Code: 103 people in 26 cases.

- “Being assembled together do an act of violence to cause a breach of the peace” in the Section 215 of the Penal Code: 171 people in 35 cases.

- Violation of the Emergency Decree: 444 people in 128 cases, which are divided into 23 cases during the declaration of a serious emergency situation in Bangkok and 105 cases involving the breaching of the Covid-19-related provisions.

When taken into account the people prosecuted for political reasons in violation of the Emergency Decree, the accumulated figures have amounted to 457 people in 136 cases.

- Charges under the Public Assembly Act: at least 87 people in 62 cases.

- Charges under the Computer-related Crime Act: at least 35 people in 40 cases.

Among all Emergency Decree cases, 35 cases contain additional charges under the Public Assembly Act, even though the Section 3 (6) of the law explicitly requires that the law not be used on public assemblies during the declaration of an emergency situation.

Out of the 268 mentioned cases, 41 have already been concluded, as the accused had settled for fine penalties at the police stage or in court. These mainly concerned charges with only fine penalties, such as those under the Cleanliness Act, failure to notify about the public assembly, or traffic obstruction.

The TLHR has made the following important observations regarding the prosecution tendency identified in March 2021

1. 27 cases alleged of Section 112 have emerged in the course of one month alone. Cases concerning online activities rose sharply.

Since the end of the hiatus with regards to the application of “lèse-majesté” in November 2020, the cases have risen steadily. In March, 27 new cases involving 22 people were reported, which raised the number of Section 112 cases to at least 74 cases involving 82 people in total (see Section 112 case statistics).

9 instances of arrests of citizens and activists were carried out both with and without warrants, including ‘Ammy’ Chai-amorn for setting fire to the royal portrait in front of the prison, Tiwakorn Vithiton for sharing posts and wearing t-shirt with the text “We have lost fait in the monarchy”, ‘Port Faiyen’ for posting three texts since 2016, “Pornchai” for sharing online posts, two youths accused for expression in front of the royal portrait during the 20 March protest, and “Justin” Chookiat for gluing paper sheets containing texts on the royal portrait at the same protest.

Arrests that took place towards the end of the month also included Piyarat “Toto” Chongthep, who was seized to be prosecuted for criticizing the royal vaccines in Kalasin province, and “Pornpimol” in Chiang Mai.

The mentioned arrests have continuously raised the number of people defending themselves against Section 112 lawsuits. This month, it was found that the Court denied the temporary release during the investigation for 7 people, including the 3 Ratsadon leaders, who were additionally charged from the 19 September rally. As a result, total of 14 people were currently being detained while awaiting trial by the beginning of April 2021 (see detention statistics).

The denial of bail also affected people who had gone to report themselves according to the inquiry officer’s warrant and had neither been apprehended nor had an arrest warrant on them. The inquiry officer then sought detention of these people from the court, who then reject their right to bail. One of such cases included Promsorn “Fah” Veerathamjaree, who went to Thanyaburi Police Station after having received the warrant for speaking in front of the Thanyaburi Provincial Court. The case was considered the first in that nature.

The visits of detainees have become more difficult as well, as the prisons, citing the Covid-19 situation, have suspended visits by both relatives and friend. On the other hand, lawyers, though permitted, must be formally appointed first. The conferral between lawyers and their clients have also been limited by the imposition of stricter measures by the court following Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak’s in-courtroom speech criticizing the justice system.

Contrary to the early period following the moratorium of Section 112, which mainly targeted on speeches at rallies, the legal actions against online expression also have a tendency to increase recently. In March, online activities have resulted in 15 new cases out of 27 in total.

One of the cases concerned Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, who was charged with both Section 112 as well as the Computer-related Crime Act for criticizing the government’s Covid-19 vaccine procurement on Facebook Live titled “The Royal Vaccines: Who Benefits, Who Doesn’t”.

Most defendants in the abovementioned cases are ordinary internet users, and the complainants are ordinary citizens or members of royalist groups, who have reported cases at the TCSD or police stations. Several cases were filed to a police station in a remote location, which added extra legal burden to the defendants.

The situation reflects the problematic enforcement of the Section 112, where, unlike the ordinary defamation law, anyone is allowed to initiate a lawsuit without being the victim themselves. As a result, the provision has been actively used by different political groups as a political tool or as a means to harass opponents.

2. The mass arrest of protestors and activists for violation of the Emergency Decree takes place more frequently

In March, the arrests of protestors or activists happened regularly, including 3 instances of mass arrest: 48 WeVo members at Major Cineplex Ratchayothin on 6 March 2021, 32 people at the REDEM’s protest on Sanam Luang and surrounding areas on 20 September, and 99 participants of the Mooban Talu Fah activity near the House of Government in the morning and evening of 28 March 2021.

The arrests were considered the largest in number since the Free Youth rally. The 20 March protest, especially, also prompted the authorities to use an excessive force not consistent with the assembly management principles, including indiscriminately firing rubber-coated bullets injuring journalists and non-participants, and arresting many individuals not related to the charges.

In all three events, the detainees were brought to a non-police-station location, such as the Region 1 Border Police Bureau or Narcotics Suppression Bureau. Not only did this practice violate the law, it also made the lawyer and relatives’ effort to track their whereabouts difficult.

The expansive extent of the arrest and prosecution of political activists on grounds of breaching the Emergency Decree, which aimed to curb the Covid-19 spread, have added 143 people in 27 cases to the statistics in March.

Besides arrests, the police officers also continued to issue warrants summoning leaders, speakers, or protestors of various protests, including those from the 9 February and 10 February protests at Pathum Wan Skywalk, those from the 13 February protest at the Democracy Monument, and those from the protest in front of the Bang Khen Police Station on 21 December 2021 during the charging process, as well as WeVo guards that had been arrested on 6 March 2021 but not taken to the Region 1 Border Control Police on the same day, whom the police also accused of attempting to flee during the arrest.

In the northeast, an increasing number of protesters also faced charges, including 23 people in the protest in front of the Phu Khieo Police Station calling for the police’s apologies to the students that were to participate in the Ratsadon On Tour camp, and 14 participants of the 20 February and 1 March protests combined in Khon Kaen. All of these instances cited the Emergency Decree as the main charge.

It is to be noted that no covid-19 infection case has been reported as a result of the political activities since the Free Youth rally in 2020.

>> One Year of the Emergency Decree to Control the Covid-19: the Impacts on the Freedom of Assembly

3. The number of youths prosecuted for political reasons has more than doubled in a month.

Among all the people prosecuted as a result of political involvement were also minors of less than 18 years old, 31 of whom have already been charged. The March statistics pointed to an increase of 18 people, or more than one fold compared to February, due to arrests of youths in various protests (see youth case statistics).

3 youths were arrested during the arrest of WeVo guards on 6 March 2021, 7 youths were arrested in the 20 September protest, and 6 youths were arrested at the Mooban Talu Fah activity. Moreover, summon warrants were issued for past protests.

Nearly all affected youths had never faced legal actions before. Further, the ages of the young people who were arrested and charged kept decreasing, as more youth of 14-15 years old faced legal proceedings, including those containing Section 112.

At the same time, the accused in the age range of 18-20 years old, which has barely passed the minor’s definition, comprise a significant group as well, reflecting the frustration towards the country’s politics among the younger generation explaining the diversity and frequency of their actions and expressions since the past year.

The increasing tendency regarding the prosecution of youths as described above reflects the shift in the state’s policy, which has relied on laws to repress citizens more heavily than last year.