COVID-19 is a pandemic whose outbreak has severe impacts across the globe. The large-scale infection began in December 2019, when the first patient was found in Wuhan, China. In Thailand, the first person who had contracted the disease was found in January 2020.

Nevertheless, in the beginning, Thailand did not report a significant number of infections. The government accordingly decided to manage the pandemic through existing legal tools until a major boxing match at the Lumpini Boxing Center, which was televised on 6 March 2020, brought about widespread transmission of the pandemic and became a “super spreader” site.

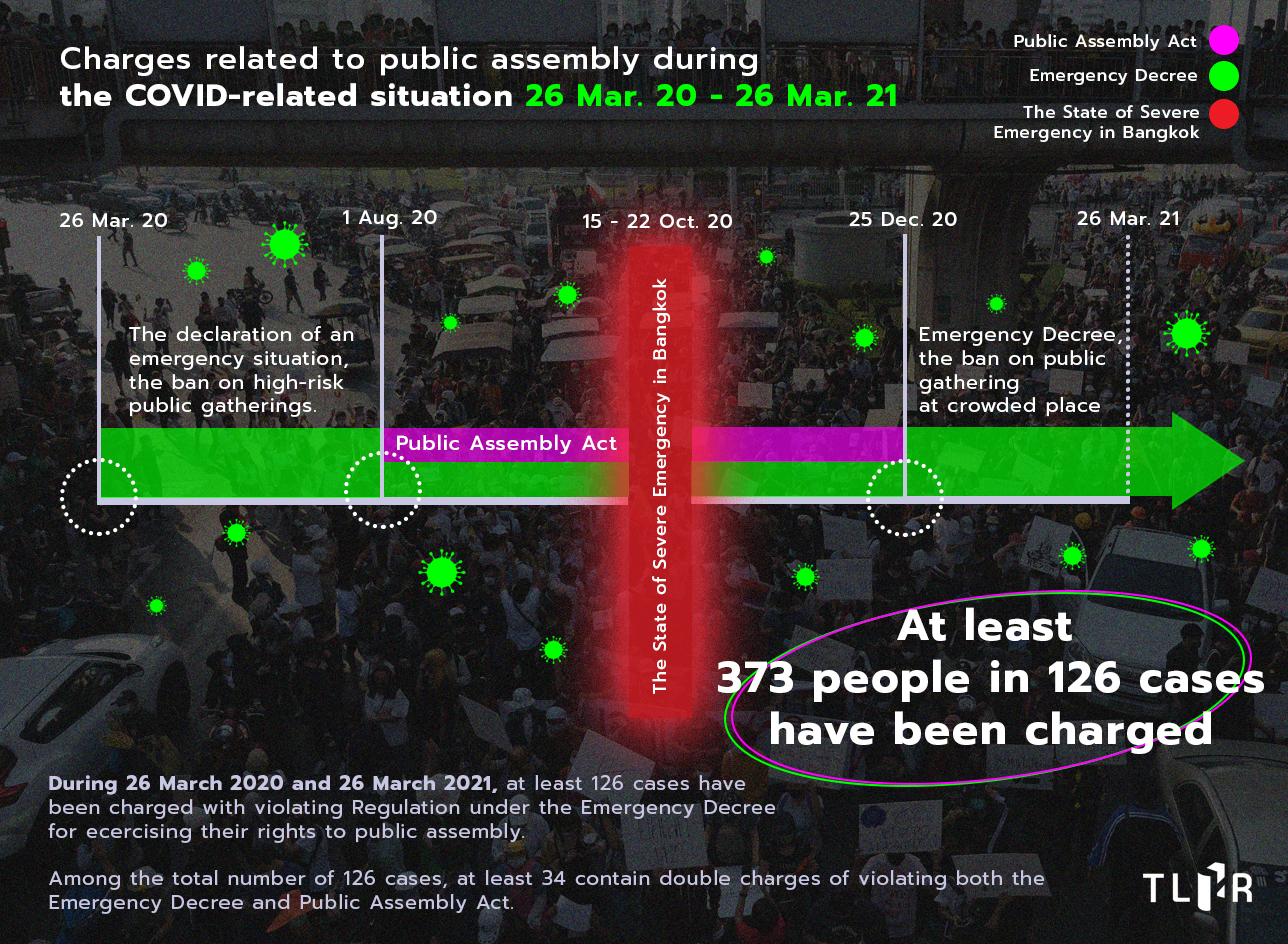

The number of infected persons eventually saw a dramatic surge and led to the government’s declaration of an emergency situation on 25 March 2020. The first period of the emergency situation lasted from 26 March 2020 to 30 April 2020.

Until now, the second wave of COVID-19 infection has surfaced, and the Prime Minister continues to extend the emergency situation every month for ten times. The current extension will be effective until 31 March 2021.

Moreover, the cabinet has recently extended the emergency situation for the 11th time for two more months until 31 May 2021. This decision has enabled the government to further prolong the state of emergency under the excuse that the decree is necessary to curb the pandemic’s second wave and achieve a nationwide vaccination.

Under Section 9 of the Decree on Public Administration on Emergency Situation B.E. 2548 (2005), the government has issued and enforced more than 18 Regulations (Hereinafter “Regulations under the Emergency Decree”) with measures on the entry ban and closure of high-risk venues, border closure, prohibition of hoarding essential goods, and organizing public assemblies or physical activities, news reporting, protection of social order, disease control, curfew enactment, and other relevant matters. The issuance of some Regulations is based on powers under the Emergency Decree or other laws, whereas others lack a clear legal basis. It must be noted that all Regulations have significant impacts on the people’s rights and freedom.

>> Read more about legal observations on the declaration of a state of emergency for combatting the COVID-19 pandemic by Thai Lawyers for Human Rights.

The impacts of these legal provisions have been remarkably intensified amid Thailand’s current political climate in which political activism continues to grow increasingly active and vibrant.

The number of cases arising from political demonstrations has been varying directly with the political climate. The government’s declaration of the emergency situation has posed a key obstacle against exercising the freedom to organize and participate in such activities.

The double weaponization of the Emergency Decree and Public Assembly Act

Within the past year, political protestors have faced various charges for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly. Initially, after the declaration of the emergency situation and subsequent lockdown from April to May 2020, not many political activities took place.

However, the commemoration event for the tenth anniversary of the 19 May 2010 military crackdown on Red-Shirt protestors and the disappearance of political exile Wanchalerm Satsaksit occurred in early June 2020. This series of incidents prompted many people to organize activities to demand justice from relevant government agencies. During that period, the authorities also pressed charges against those involved in such activities for violating disease control measures under the Regulations under the Emergency Decree.

Meanwhile, Section 3 of the Public Assembly Act B.E. 2558 (2015) (Hereinafter “Public Assembly Act”) stipulates that the Act shall not be applied during the declaration of the state of emergency. Instead, one must comply with the Emergency Decree. Therefore, protestors who participated in political activities during that period would face charges for violating the Emergency Decree, not the Public Assembly Act.

Once the COVID-19 outbreak subsided, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-ocha issued Regulation No. 13 under the Emergency Decree, whose Paragraph 1 stipulates, “The organization of group activities or the people’s exercise of their rights to assemble may be carried out within the scope of the exercise of rights and liberties under the constitution and other laws per the criteria prescribed by the law on public assembly.” The Regulation took effect on 1 August 2020.

There is also an issue with the implementation of the foregoing Regulation. While it is only a subordinate law, it contradicts Section 3 of the Public Assembly Act. Even if the law on public assembly could then be reactivated, the scope of enforcement remained unclear because the law extensively covers rules, duties, rights guarantee, judicial oversight mechanisms, and penalty. The Regulation prescribes that the law enforcement shall adhere to legal principles in the public assembly law. However, it turned out that the authorities did not only use the Public Assembly Act to prosecute the protestors. During this period, they also continued to charge them for violating the Regulation issued under the Emergency Decree in at least 32 cases.

Regulation No. 13 under the Emergency Decree was effective until 25 December 2020. Then the Prime Minister issued Regulation No. 15 under the Emergency Decree whose Paragraph 3 states, “It is prohibited to assembly, carry out activities, gather at any crowded place, or commit any act which may cause unrest in areas determined by the Chief Officer responsible for resolving the emergency situation related to security affairs.”

Accordingly, from 25 December 2020 onwards, the authorities had stopped enforcing provisions in the public assembly laws. However, they have started to ban protest activities in crowded venues stringently.

The declaration of the State of Severe Emergency in Bangkok due to protest escalation

When Regulation No. 13 under the Emergency Decree was still in force, the Prime Minister decided to declare the state of severe emergency in Bangkok from 15 October 2020 to 22 October 2020. He also issued an additional Regulation under Sections 9 and 11 of the Emergency Decree whose Paragraph 1 “prohibits any gathering or illegal assembly of five or more people in any places or any acts that could instigate public unrest and disorder.” The Regulation also cites the political turmoil during protest activities and the alleged attempt to interrupt a royal motorcade on 14 October 2020.

During this period, there were two overlapping declarations of the state of emergency in place in Bangkok. As a result, the prosecution against those violating the Emergency Decree must primarily follow the provisions under the Regulation issued under Sections 9 and 11 of the Emergency Decree.

Conversely, at that time, the police officers chose to prosecute protestors under the Public Assembly Act, among other charges, in at least two cases – the one linked to the #19Oct rally at Kasetsart Intersection and the other linked to the #19Oct rally in front of the Bangkok Special Prison.

During this period, the authorities also filed charges under Section 110 of the Criminal Code against protestors who participated in the demonstration on 14 October 2020 when the royal motorcade drove past the protest venue near the Government House. The protest caused some delay to the royal motorcade. After the incident, five protestors have been accused of “committing an act of violence against the Queen.” If found guilty, they could face imprisonment of 16 to 20 years.

Also, one of the two defendants detained while awaiting trial has been facing discriminatory treatment, as he has been subject to solitary confinement at the Bang Kwan Central Prison, which is the maximum-security prison for security detainees. The authorities also monitor his cell closely through surveillance cameras. The Director-General of the Corrections Department attempted to justify the surveillance by claiming that it was part of the prison’s disease control measures.

The surge of cases linked to the escalation of political tension

During 26 March 2020 and 26 March 2021, at least 373 people in 126 cases have been charged with violating Regulations under the Emergency Decree for participating in political demonstrations.

Among the total number of 126 cases, at least 34 contain double charges of violating both the Emergency Decree and Public Assembly Act.

Aside from charges under the Emergency Decree and Public Assembly Act, protestors also face many other serious charges, such as lese-majeste, sedition, and involvement in secret society or criminal association.

Freedom of assembly under the state of emergency

1. Prioritizing control over political protests

Freedom of assembly is considered one of the fundamental freedoms in any democratic regime. It is also guaranteed under Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). State parties of the ICCPR must respect such freedom and provide protection for those who wish to exercise it. During a public emergency, the State parties may derogate from their obligations to Article 21. However, while they may be permitted to impose some restrictions or curb certain freedom upon declaring a state of emergency, Section 4 of ICCPR still requires them to take only steps that are strictly necessary and proportionate to the situation.

However, it has become evident that, throughout the past year, the authorities have permitted both public assemblies and other non-assembly activities featuring a gathering of many people to take place, especially after the first wave of pandemic outbreak subsided. However, political protests have been subject to additional scrutiny and stringent law enforcement, even though they are held peacefully in venues that are not crowded and prone to risks of mass transmission. Protestors continuously face charges and encounter a series of violent crackdowns carried out in a manner that fails to respect international human rights standards.

Meanwhile, there is no report that any political assemblies throughout the past year have led to an outbreak of COVID-19.

2. Inconsistent law enforcement which burdens the protestors

While the Communicable Disease Act B.E. 2558 (2015) is the most pertinent law for tackling the ongoing pandemic outbreak, the government has chosen to impose the Emergency Decree and declare an emergency situation over the past year. Under this exceptional legal regime, the Emergency Decree, which had been designed for security-related public emergency, has been misused for the wrong objectives and turned into a political weapon for clamping down on freedom of assembly.

The inconsistent law enforcement also involved the issuance of the Regulations under the Emergency Decree as a subordinate law to suspend the enforcement of the Public Assembly Act. In spite of these Regulations, the authorities still cherry-picked different legal provisions from the Act to determine conditions and penalties for prosecuting the protestors.

While the authorities selectively enforced some sections of the Public Assembly Act, they conversely did not comply with other key provisions, such as the requirements to ask for the Court’s order to terminate a public assembly or adhere to a plan for overseeing a public assembly. This inconsistency was manifest in the case of the protest crackdown on 17 November 2020 in front of the Parliament at Kiak Kai Road and the shooting of journalists on duty during the protest crackdown on 20 March 2021 at Khao San Road.

3. Absence of accountability and oversight efforts through judiciary mechanisms

The Emergency Decree provides legal immunity for the authorities exercising powers under almost every provision of the law. Section 16 stipulates that a Regulation, Notification, Order, or action under this Emergency Decree shall not be subject to the law on administrative procedures and the law on the establishment of Administrative Court and Administrative Court Procedure.

Section 17 of the Emergency Decree also prescribes that a competent official and any person having identical powers and duties as the competent official under this Emergency Decree shall not be subject to civil, criminal, or disciplinary liabilities arising from the performance of their duties to stop or prevent an illegal act. Such performance must be in good faith, non-discriminatory, and reasonable in specific circumstances, and does not exceed the extent of necessity. Nonetheless, this provision does not preclude the right of a victim to seek compensation from a government agency under the law on liability for the wrongful act of officials.

However, many people have previously attempted to employ oversight mechanisms in judiciary bodies. Yet, they found several limitations stemming from the exception mentioned earlier of the Administrative Court’s jurisdiction and absence of accountability for the authorities.

For example, the lawsuit for revoking the state of severe emergency, which was initiated in October 2020, was subject to undue delay. The Court has deferred the settlement of issues to be in June 2021. Meanwhile, the Civil Court decided to dismiss the tort lawsuit in the case of shooting journalists on duty during the protest crackdown on 20 March 2021 at Khao San Road only within one day. Furthermore, the most recent tort case on another protest crackdown on 17 November 2020 in front of the Parliament was filed to the Court on 26 March 2021.

As Thailand has imposed a state of emergency for curbing the spread of COVID-19 for more than one year, the use of special security laws might be turning into the “new normal” in Thai society. In a bid to prevent that, Thai Lawyer for Human Rights urges the government to use the Communicable Disease Act for its intended purposes, revoke the state of emergency immediately, and amend the Emergency Decree to enable parliamentary oversight over the declaration of the emergency situation. While reviewing these policy recommendations, the government shall also enforce the law cautiously under a necessary scope in a limited timeframe to minimize its impact on the rights and freedom of the people and maximize the law’s efficacy and speed in controlling the spread of COVID-19.