Along with the scorching heat of April, the political temperature in Thailand has been rising steadily as the general election approaches. Meanwhile, the political lawsuits continue their courses. At least five more people have been charged with lèse-majesté last month while the Public Assembly Act and Section 116 are still used to accuse politicians and activists. As such, the problematic legal enforcement in terms of overbroad interpretation of laws remains a critical issue.

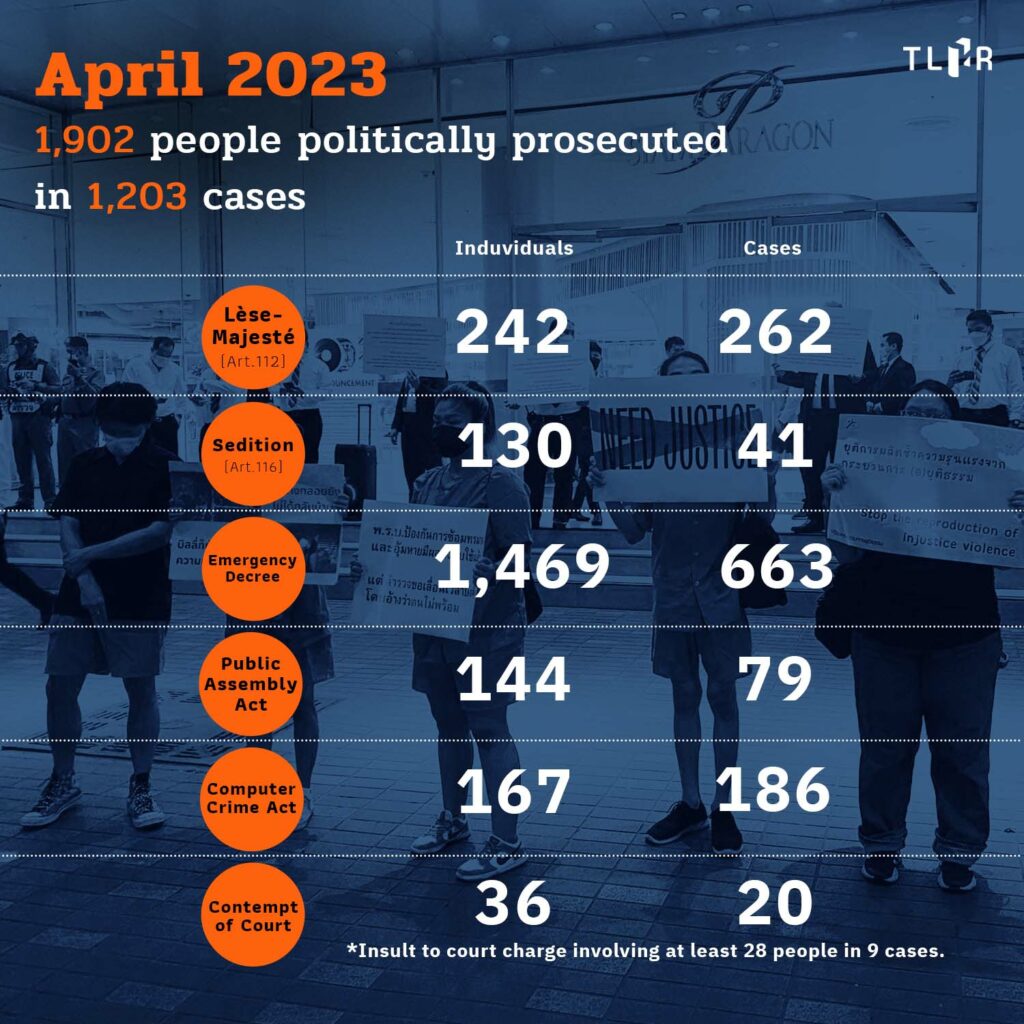

According to the TLHR statistics, at least 1,902 people in 1,203 cases have been prosecuted due to political participation and expression since the beginning of the “Free Youth” protest on 18 July 2020 until 28 February 2023.

Among this number are 211 cases involving 284 children and youths under 18 years old, including 41 below 15 years old and 243 between 15 – 18 years old.

Compared to March 2023, this month’s statistics saw an increase of 4 people and 16 cases (only counting those who have never been charged before).

If we also count and include those who are charged redundantly in multiple cases, we have found that there would be at least 3,827 instances of prosecution in total.

The prosecution can be grouped according to key charges used, as follows:

1. The royal defamation or “lèse-majesté” charge under Section 112 of the Penal Code: at least 242 individuals in 262 cases.

2. The “sedition” charge under Section 116 of the Penal Code: at least 130 individuals in 41 cases.

3. Charges of violation of the Emergency Decree: at least 1,469 people in 663 cases (since May)

4. Charges under the Public Assembly Act: at least 144 people in 79 cases.

5. Charges under the Computer Crime Act: at least 167 people in 186 cases.

6. Contempt of court charge: at least 36 people in 20 cases and insult to the court charge involving at least 28 people in 9 cases.

Out of the mentioned 1,203 cases, 343 have been concluded, meaning over 860 cases are still ongoing at various stages.

.

.

The prosecution trends in April 2023 show the following key developments:

Five more people charged with lèse-majesté . Summon and arrest warrants issued for activists.

As far as we are aware, at least five more people have been accused of the lèse-majesté law in six different cases last month. This means activists are still continuously targeted by lawsuits for their political expression. Key cases include that of ‘Sainam’ and ‘Oil’. The two activists were informed about the arrest warrants issued in the case of posting an image of a three-finger salute on the Equestrian statue of King Chulalongkorn, on 7 March 2023 and reported themselves during the Songkran holidays.

The accuser in this case was a member of the People’s Center to Protect the Monarchy, claiming that using a royal site for a symbolic expression representing peace, freedom, and fraternity was considered an insult or an offense towards the king. It remains unclear why and how such a symbolic expression would be regarded as a defamation or an insult and constitute an element of crime under Section 112.

.

The police also made arrests for two previous cases of political expression, namely ‘Bang-ern’, a Khon Kaen-based artist who spray-painted the mural of the Emerald Buddha Temple and was charged with lèse-majesté for sharing images on Facebook in March 2022 and ‘Sathaporn’, a Udonthani citizen charged with flashing the three-finger salute and shouting at a royal motorcade on Rajadamnoen Avenue in May 2022.

Police from Mueang Khon Kaen Police Station also issued warrants containing a lèse-majesté charge summoning Songpol “Ya Jai” Sonthirak, a Talu Fah member, in a lawsuit initiated by a Thai Pakdee Party MP. As Ya Jai has postponed his hearing of charge, the motivation behind the accusation remains unknown to date.

The TLHR has modified the statistics related to the case against Anon Nampa and Parit Chiwarak involving their speeches made at the protest at the Chiang Mai University Art Center on 23 November 2020. After the case was indicted, it was found that the Chiang Mai Provincial Court had decided to conduct a separate trial into two. Thus, the case will be counted as two instead of one.

.

.

Last month, the public prosecutor indicted at least five lèse-majesté cases while the Court of First Instance and the Appeal Court each passed a verdict for one case. In the case against Nawat “Amp”, an activist accused of making a speech at the 13 February 2021 protest, the Appeal Court sentenced him, following a decision to confess, to a jail term of one year and seven months without suspension, reasoning that the defendant had committed the same offense in multiple cases. That said, Nawat has been granted bail during the appeal to the Supreme Court.

Another notable verdict announcement is for the case against “Wutthipat”, a 29-year-old private company employee accused of posting a comment about King Rama VIII’s death. The Court of Appeals Region 1 modified the decision of the First Court establishing that an insult and defamation against the former king would naturally affect the current king, as well as people’s emotions, which could eventually affect national security.

This was the second case in the past year where the Appeal Court decided to modify the lower court’s decisions of acquittal, who held that the protection under Section 112 did not extend to former kings. Interpreting the said provision to cover former kings poses a critical problem and reflects the inconsistency in the court’s discretion. It has created ambiguity over law enforcement and will complicate opinions, researches, and understandings of the country’s history later on.

Meanwhile, at least two people involved in lèse-majesté cases, namely “Wut” and “Yok”, were under detention throughout the month. In fact, both have already spent more than a month behind bars. Yok, in particular, a young person detained at a juvenile detention center, has been insistently refused the judicial processes, appointing a lawyer, and applying for bail.

.

.

One more case of not notifying the public assembly was charged, whereas Emergency Decree cases were dropped by the courts/public prosecutors.

Last month, one more case related to protests emerged. That is, the case against eight activists who wore inmate uniforms on Bangkok sky trains on 17 April 2022 to commemorate 9 years of Porlajee “Billy”’s disappearance. They were summoned on warrant by police of Bang Sue Police Station for not notifying the assembly in pursuant to the Public Assembly Act. The eight denied all charges.

This case has raised the question whether this activity was regarded as a public assembly, since they did not invite the public to join, and if they did, the public would not just be able to change into that kind of uniform immediately. This will be a key point for their defense.

As for the cases related to protests between 2020 and 2022 in courts, verdicts have been slowly rolling out. In April, two Emergency Decree cases – the Hat Yai car mob case and the Phetchabun car mob case – were dismissed. On the other hand, the court ruled one guilty, namely the case against three citizens arrested for joining the 7 August 2021 protest, and sentenced them to 2,000 Baht in fine each.

Moreover, eight We Volunteer members, who had been arrested prior to the 7 August 2021 protest under the charge of secret organization, were acquitted by the Criminal Court, seeing that the plaintiff’s evidence could not adequately prove that the alleged act by the eight members fell into the scope of this offense. That said, the court convicted them under the charge of carrying a telecommunication device without permission.

Meanwhile, there were also reports of protest cases that were not indicted by the public prosecutors. These include the case against P-move and the #SaveBangkloi coalition from a protest in early 2022 and the Narathiwas car mob case.

According to TLHR statistics as of the end of April 2023, at least 514 cases related to political protests during 2020 – 2022 under the charge of Emergency Decree are ongoing. Many have been newly prosecuted by the public prosecutors. Some are during appeal even though the Court of First Instance has already dismissed them.

These cases are set to continue after the upcoming general election. Some activists have been carrying the burden of going to trials for their political participation. Likewise, certain laws, such as the Public Assembly Act, will still be used to stifle protests. These are some of the things that need to be monitored further.

.

.

Section 116 is used to accuse opposition politicians, while the Supreme Court’s verdict sets guidance for the interpretation of Section 14(2) of the Computer Crime Act.

In April, a new lawsuit under the charge of Section 116 of the Penal Code, also known as the “sedition” charge, arose. Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, leader of the Progressive Movement, has been accused at Nang Loeng Police Station by Natthaporn Toprayoon based on his comment about the burning of the royal portrait in Club House in March 2021. One year later after the incident, the police decided to issue a warrant to prosecute him.

The public prosecutor also issued an order of indictment for the case against two Thammasat graduates, “Sathorn” and “Lookmark”, for the 10 August 2020 protest consisting of Section 116 as the main charge. Earlier, seven people had already been prosecuted under the same charge at the Thanyaburi Provincial Court, raising the total number of people prosecuted to nine.

The issue of Section 116, the provision in the chapter on security, being interpreted extensively to restrict political expression, is the legacy of the NCPO era. Largely, the trials of these cases were concluded with the courts acquitting the defendants.

.

.

One month ago, there was an interesting Supreme Court ruling, such as the case of Suchanan, a transgender woman who was charged with the Computer Crime Act, Section 14 (2) due to posting messages that the Deputy Commissioner and police officers of the Crime Suppression Division might be behind the attack on activists in year 2019

For this case, both the Court of First Instance and the Appeal Court sentenced to 6 months in prison without parole. However, the Supreme Court reversed a judgment by dismissing the case. The Supreme Court viewed that the elements of Computer Crime Act, Section 14 (2), apart from the intention to import false computer data, have to consider whether the information was in a manner that was likely to damage the country’s security or cause a public panic by mainly considering the public’s opinion.

However, for this case, there was no public panic and damage to the country’s security. Having Considered the plaintiff’s witnesses, it could not be heard that importing information into the computer system caused public panic, damaged the security of the country, or caused panic to the people in general according to the charge. Therefore, it has not been considered as an offense on this charge. This kind of judgment is likely to affect the exercise and interpretation of the Computer Crime Act in Section 14 (2) to be more precise.