The hashtag #19SeptReturnPowerToThePeople was widely used to refer to the two-day demonstration held by “Ratsadon Group” at the Royal Plaza and Thammasat University from 19 to 20 September 2020. This rally is well-known for several of its distinctive features. It is estimated that around 200,000 protestors attended the event; many camped out at the Royal Garden and Thammasat University. The organizers had also set up a large stage where numerous people could go up and take turns delivering speeches and leading political activities throughout the night.

Furthermore, in the early morning of 20 September, there was a ceremony to install a plaque of “2020 People’s Party” on the concrete floor of the Royal Garden. Two student protest leaders- Parit Chiwarak and Panussaya Sithijirawattanakul- took turns reading the Declaration of the 2020 People’s Party. The Declaration addressed the monarchy’s over-expansion of its power and changing roles and reiterated the student movement’s 10 core proposals on reforming the monarchy to ensure that the royal institution can co-exist with Thailand’s contemporary democratic regime.

After the public reading of the Declaration, the organizers announced that they would revoke their initial plan to march towards the Government House to call for the resignation of Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-o-cha. Instead, they decided to submit a letter on their 3 demands, along with the aforementioned 10 proposals on monarchical reforms, to the President of the Privy Council at the Privy Council Chambers located inside Saranrom Royal Garden, which is not far from the Royal Plaza. They hoped to request the privy councilors who serve as the King’s advisors to inform the King of the Thai people’s will.

Read more: Overview of the #19SeptReturnPowerToThePeople demonstration at the Royal Plaza

Following this demonstration, a total of 22 people has been charged for their participation in this activity. The public prosecutor indicted 4 of them on 9 February 2021 and the remaining 18 on 8 March 2021. Among all the defendants, 7 face “lèse-majesté” charges under Article 112 of the Criminal Code; none of them were granted bail.

This case marked the first indictment under Article 112 since the Free Youth Group’s first demonstration to call for democratic changes in Thailand on 18 July 2020. Various developments linked to this case raised serious questions regarding the Thai judiciary system. Below are the summaries and analyses of such developments by Thai Lawyers of Human Rights (TLHR).

1. Public prosecutor rushed to file the indictment order within 15 days

1. Public prosecutor rushed to file the indictment order within 15 days

The public prosecutor from the Office of the Attorney General (Department of Special Criminal Litigation 7) received this case’s inquiry file for the first time on 26 January 2021. Previously, the inquiry officer from Chana Songkram Police Station handed Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak, alongside his inquiry file, to the public prosecutor before the indictment hearing, which was scheduled on 9 February 2021. Similarly, the inquiry files of Patiwat “Mor Lam Bank” Saraiyaem, Somyos Prueksakasemsuk, and Anon Nampa were scheduled to be handed to the public prosecutor on 28 January and 1 February 2021, respectively.

Subsequently, the public prosecutor used only 15 days to examine the inquiry file and order an indictment of the 4 activists under various charges – most notably, Article 112 (Lese majeste) and Article 116 (Sedition) of the Criminal Code. The decision was made, although the quartet petitioned the prosecutor to carry out an additional examination of 2 more witnesses on many issues, including human rights issues concerning Articles 112 and Article 116. The public prosecutor provided an explanation that the defendants’ petition would not result in any changes in their decision. Such a statement prompted Penguin to declare on that day, “The public prosecution system in this country has zero regards for the people’s rights and liberties.”

2. 8 defendants denied bail for over a month

2. 8 defendants denied bail for over a month

As soon as the trial began, the Court acted as if the defendants had already been found guilty. The first 4 defendants indicted for alleged violations of Article 112 were denied bail, even though the prosecutor did not submit any objection to the bail applications. Judge Tewan Rodcharoen, Deputy Director-General of the Criminal Court, stated in the court order, “… The defendant committed their actions repeatedly on several different counts and instances, thus violating the same offense over and over again. Therefore, there are reasonable grounds to believe that they may re-offend should they be granted temporary release….”

The Court of Appeal later affirmed this ruling and denied bail for the activists, as if it already prejudged the activists as guilty. The four defendants indicated in their appeal that the Criminal Court’s denial of their bail requests contradicted the principle of the presumption of innocence until proven guilty by a final verdict. Meanwhile, the Court of Appeal justified their decision by stating, “According to the indictment decision, the defendants committed their offenses jointly with one another. Their actions could cause damage or public disorder, resulting in large-scale impacts. The defendants had delivered speeches tarnishing the monarchy’s reputation.”

The Court issued a similar ruling to deny bail for Panussaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul, Panupong “Mike” Jadnok, and Jatupat “Pai” Boonpattararaksa after the public prosecutor indicted them in Court on 8 March 2021. These seven lese majeste defendants encountered the same fate when attempting to appeal the Court’s decision on their bail requests multiple times. The Court affirmed the previous rulings by the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal, insisting that bail could not be authorized due to insufficient reasons for overturning the earlier decisions.

Apart from the 7 lese majeste defendants who delivered speeches during the demonstration, Chai-amorn “Ammy” Kaewwiboonpan has also been indicted for alleged violations of Article 116 and did not receive bail. Such indictment took place after he was arrested and detained in a separate case in which he faces a charge under Article 112 for allegedly burning the King’s portrait in front of Klong Prem Prison.

As the activists failed to secure bail after many attempts, the public became increasingly aware of this issue and advocated for the Court to restore the political detainees’ rights to bail. Accordingly, the Court gradually started to grant a provisional release for the activists during April and June 2021. Before the series of bail authorization began, each had been deprived of their liberty for at least 47 days or one month and a half.

Dating back to October 2020, the seven defendants had previously been arrested and denied bail by the Court during their remand phase, even though they were only facing sedition charges under Article 116. All were detained from 7 to 17 days before the Court granted bail for Jatupat and issued an ensuing order that the rest also should not be held in remand any longer.

3. Corrections authorities rushed to detain Panussaya-Panupong-Jatupat but failed to comply with the detention warrants’ orders

3. Corrections authorities rushed to detain Panussaya-Panupong-Jatupat but failed to comply with the detention warrants’ orders

After the Court accepted to try the 18 remaining defendants in this case on 8 March 2021, 3 activists indicted under Article 112, including Panussaya, Panupong, and Jatupat, were taken into a van, which left the Court at 3:30 pm. Their departure left family members clueless about their fate and whereabouts. Without having any chance to bid farewell, Jatupat’s mother and Panussaya’s sister cried aloud for the injustice faced by their loved ones. Later, at 4:00 pm, the Court ruled against the activists’ bail applications. The Department of Corrections’ rushed operations prompted suspicion amongst the public. Under the law, the official could technically take the defendant to prison immediately after the Court accepted the indictment and issued a detention warrant. However, if the defendant wishes to apply for bail, the authorities usually will wait until the Court delivers its decision to allow for a temporary release.

Moreover, the Department of Corrections officials took Panupong and Jatupat, together with Piyarat “Toto” Chongthep, who was also denied bail in a separate case where he was charged for alleged membership of a secret society, to Thonburi Special Prison. This practice contradicted the detention warrant that specified Bangkok Remand Prison as their legal place of detention, thereby raising questions about the Department’s treatment of activists. In response, the defendants’ lawyer filed a petition requesting the Court to order the Department to transfer them to Bangkok Remand Prison. The petition argued that the defendants should be held in a detention facility within the Court’s area of jurisdiction. Having the defendants in prison far from the Court could affect the detainees’ rights to access their lawyers and relatives, as those wishing to visit them could be subject to further inconveniences due to the distance of the prison.

Following the lawyers’ petition, the Court summoned relevant parties for an inquiry. The Department of Corrections officials justified their actions by citing the Order of the Department’s Director-General dated 10 March 2021, which ordered retrospectively to hold detainees in Thonburi Special Prison from 8 March 2021 onwards. The Court then ruled that the detention of the three activists in Thonburi Special Prison was lawful. It explained that an unprecedented number of people were gathering in front of the Criminal Court and Bangkok Remand Prison. Fearing that serious public disorder might break out, the Department’s Director-General exercised his discretion by moving the three to Thonburi Special Prison and subsequently informing the Court in retrospect. However, as the disorder had ended, the Court allowed the three to be transferred back to Bangkok Remand Prison on 15 March 2021.

4. Prison authorities conducted COVID-19 testing of six detainees in the middle of the night

Following the Court’s decision, Panupong and Jatupat, the defendants in this case, and Piyarat, another defendant in a separate case, were transferred to Bangkok Remand Prison per the detention warrant and court order. During their time in Bangkok Remand Prison, the three of them, together with four other detainees, were taken out of their cells four times in the middle of the night by the authorities who claimed that it was for conducting COVID-19 testing. This practice was inconsistent with the prison’s regular protocol, which prescribes that no detainee should be brought out of their cells after midnight. The incident triggered overwhelming fear among the activists who believed that they could be subject to fatal physical harm. Therefore, the following morning, Anon wrote a complaint letter to the Criminal Court about this incident.

During the examination hearing of his complaint, Anon declared before the Court, “Your Honor is the only person who could save my life. Neither my family members nor lawyers could help me. Your Honor, do you know that the person sitting before you is about to die?”

Eventually, the Court ruled that the prison’s medical operation under the supervision of Dr. Weerakit, Deputy Director-General of the Department of Corrections, only aimed to conduct COVID-19 testing. The isolation of Panupong, Jatupat, and Piyarat, which put them in a different detention place, did not intend to threaten, harass, or harm Anon and other activists.

The Court added that Anon and other activists were, nonetheless, only being held in pre-trial detention. Therefore, their rights and liberties, as well as human dignity, shall be upheld. The prison authorities’ action did not constitute a violation of the law; however, it failed to respect the detainees’ rights properly. The Court, thus, ordered that the prison authorities must carry out their duties in a cautious manner to ensure that the protection of the rights of Anon and others as guaranteed under the law.

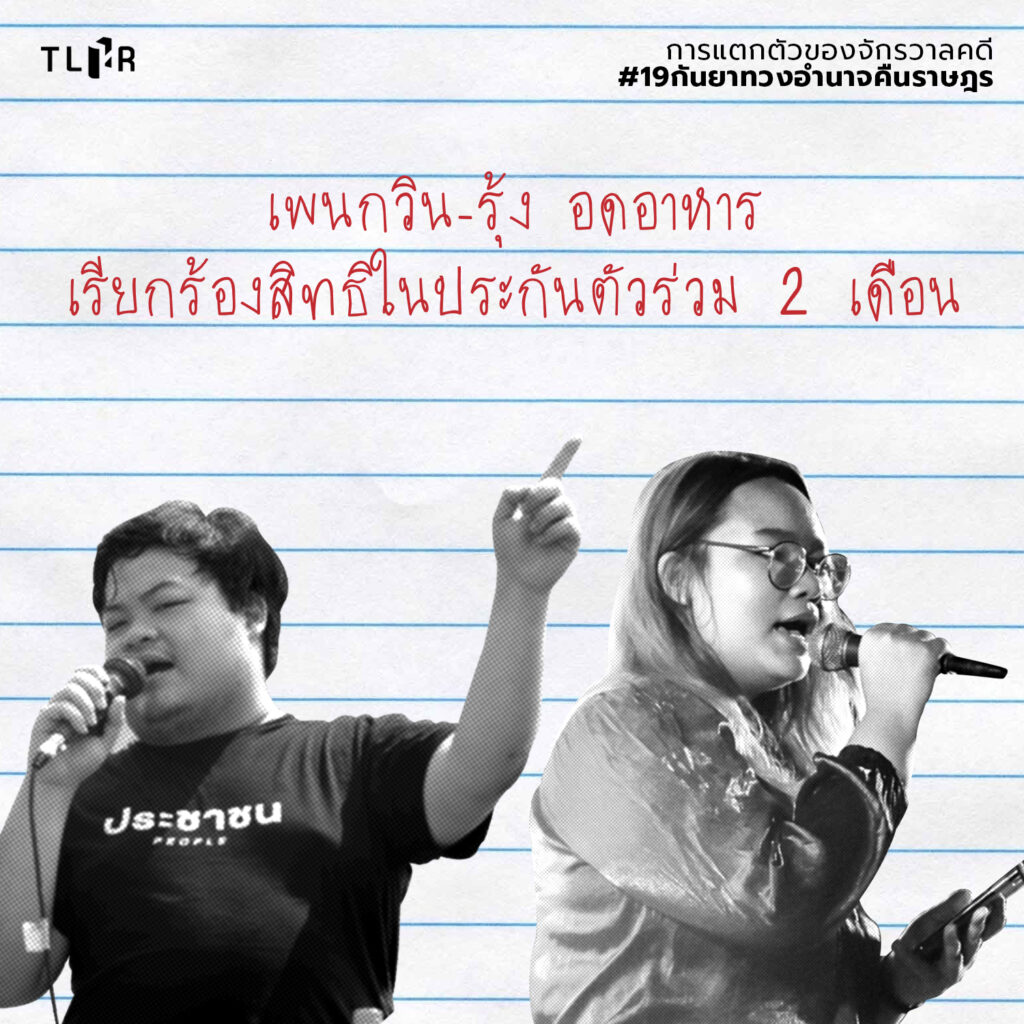

5. Parit-Panussaya went on hunger strike to demand the right to bail for more than two months

5. Parit-Panussaya went on hunger strike to demand the right to bail for more than two months

On 15 March 2021, Parit, who had been in detention for 35 days, announced that he would go on hunger strike inside a courtroom during a witness examination hearing. That hearing marked his fifth attempt to file a bail application. Even though he informed the Court that he needed to be released to fulfill his educational requirements, the Court refused to consider his request seriously. Consequently, he announced to go on hunger strike to demand the right to bail. “I do not have any intention to take my own life, but I will torture myself. My suffering shall serve as the clearest evidence of the injustice that I am facing, as a spark that lights up the fire in your conscience, and as a proof that the truth is not afraid of any suffering whatsoever.”

One remarkable part of Parit’s announcement said, “Article 112 of the Criminal Code can be compared to a malignant cancerous tumor that eats away the Thai democracy. Throughout the past decade of political conflicts, Article 112 has been used as a weapon to suppress the political opposition countless times.

Fourteen days later, the next witness examination hearing took place. Parit was taken to the courtroom in a state of fatigue, slumped in a wheelchair and tethered to a saline drip. One day later, Rung announced in tears that she would also go on hunger strike in solidarity with Penguin. She said, “I dream of a better society and future… I believe that we are fighting so that we could live on rather than die. However, if someone has to die, that death shall benefit the living… I hope that our deaths will turn into the stream of hope for our society.”

Contrary to the wishes of both activists that their decisions will provoke the conscience of judges and Thai people in general, the Court continued to refuse to grant bail to them. On the 47th day of his hunger strike, Penguin began suffering from rectal bleeding and found tissue-like materials in his excretion, which required him to be hospitalized. Many other detainees then decided to join hands with him and choose this approach of fighting. Promsorn “Fah” Veerathamjaree, Pornchai, Nattanon “Frank” Chaimahabut, and Wanwalee “Tee” Thammasattayam, and some other activists decided to go on hunger strike in front of the Criminal Court. Meanwhile, many ordinary citizens also went on a strike in their day-to-day life.

On the 38th day of her hunger strike, Rung was granted bail. Meanwhile, Penguin had to remain on strike for up to 58 days.

6. Imposition of restrictions impacting all detainees, including additional court rules, closure of court basement, and prohibition of visiting and buying food for detainees

6. Imposition of restrictions impacting all detainees, including additional court rules, closure of court basement, and prohibition of visiting and buying food for detainees

In response to Parit’s reading of his statement in the courtroom, the Criminal Court issued the Rules on the Maintenance of Peace and Order in the Premise of the Criminal Court dated 17 March 2021. In front of its staircase, the Court also set up a large vinyl sign that lists down 6 protocols for self-conduct in courtrooms. The first 2 protocols prohibit those disturbing the order or supporting such an act from entering or exiting the Criminal Court and trial rooms.

Apart from issuing the additional rules, the Court also barred family members from going to the basement floor to buy food for the defendants who were being held in detention. During the witness examination hearings on 29 March and 7 and 8 April 2021, the authorities informed the family members that the Court would feed everyone. On some days, the Court put on the sign “No visitation” – possibly as a measure to hinder people from visiting the Ratsadon leaders to give them moral support and prevent the media from taking photos or communicating with them. At times, they would shut an iron door and block the basement with a whiteboard to make sure that the journalists could not capture a picture of Parit sitting on his wheelchair and tethered to a saline drip. These measures are unnecessarily stringent. They affected not only the rights of the detainees and defendants in this case but also those of detainees in any other case.

7. Separate registration – Stringent control outside and inside the trial room – Inability of family members and lawyers to speak freely with defendants in detention

7. Separate registration – Stringent control outside and inside the trial room – Inability of family members and lawyers to speak freely with defendants in detention

Typically, the Criminal Court would require checking visitors’ bags and national ID cards. However, during the hearings for the #19SeptReturnPowerToThePeople case, many additional measures were put in place to impose more stringent controls. For example, security guards set up a checkpoint to check ID cards in front of Krungthai Bank, located at the Court’s entrance. In addition, dozens of riot control police officers were stationed around the Court’s fence and entrance gate. On some days, there are police cars, water cannon trucks, prison vans, and even barbed fences around the Court’s premise.

Criminal Court officials would ask questions and require visitors to register their information. On the other hand, those visiting the Court for purposes related to the #19SeptReturnPowerToThePeople case must register themselves separately. Family members of the defendants in detention would be authorized to enter the trial room. In contrast, observers could only watch the trial via a live broadcasted video-conferencing session. These two groups would receive different colors of the neck strap for holding their visitor cards. On 6 May 2021, there was a witness examination hearing for Panussaya’s bail application. The Court officials set up a video camera to record visitors entering the Criminal Court’s premises. As they walked into the Court, they were required to hold up their national ID cards and remove their face masks to allow the camera to capture their faces and information on their national ID cards.

In front of the trial room, an iron fence was set up to block unrelated parties from entering the room. Although the Court did not order that the trial shall be conducted in secret, a security guard said, “We are using the thickest fence to block [the trial room].” Only 2 family members per defendant could enter the trial room. Someday, the authorities were so strict that they prohibited those who were not relevant to the case from standing or walking near the trial room and using the lady’s room.

The atmosphere inside the trial room was filled with tension. Those who wished to enter the room must give their mobile phones to the authorities who would keep the devices in a zipper bag. Family members were required to sit at the back of the room, which was so far from the defendants that they could not speak or even see each other’s faces. At least 20 officers from the court police unit and the Department of Corrections attended every trial to keep an eye on the family members, ensuring that they did not approach the detainees. The authorities claimed that the family members needed to ask for the Court’s permission every time they wished to do so. Even defense lawyers were not capable of speaking and providing counsel for the defendants confidentially. They were always accompanied by the Department of Corrections officials who would be surveilling on what they were talking or writing about.

In fact, those indicted in this case had been subject to excessive restrictions on their freedoms since the date scheduled for the public prosecutor’s indictment decision. On that day, riot police officers were tasked to guard the Office of the Attorney-General. Those unrelated to the case could not observe the indictment hearing. Visitors were required to register their full names with the authorities before entering the Office of the Attorney-General.

8. Anon wrote a statement on “disavowing the injustice system”

8. Anon wrote a statement on “disavowing the injustice system”

The excessively stringent measures imposed by the Court and Department of Corrections created significant pressure for the defendants, their family members, and defense lawyers. Such pressure mounted even further as the Court repeatedly denied bail for the seven defendants indicted for alleged violations of Article 112 and continued to authorize their pre-trial detention. Thus, on the afternoon of 8 April 2021, Anon Nampa wrote the “Statement on disavowing the injustice system” by pen and submitted it to the Court. The statement presented his will in releasing the defense lawyers of their duties due to the unfairness they had encountered while fighting this lawsuit. Anon regarded all the developments throughout the entire court proceedings as the “destruction of human dignity and judicial harassment aimed at silencing dissent and turning a trial room into a prison.” As a former law student, professional lawyer, and a Ratsadon Group member with strong commitments to demanding monarchical reforms, Anon affirmed his position that he could no longer participate in this injustice system.

9. 21 defendants released their lawyers from their duties, citing the trial proceedings’ disregard of the defendants’ rights

9. 21 defendants released their lawyers from their duties, citing the trial proceedings’ disregard of the defendants’ rights

Anon was not the only person who declared his stance by making his statement on disavowing the injustice system. After the witness examination ended on 8 April 2021, all the defendants, except Patiwat “Mor Lam Bank” Saraiyaem, filed a request to release their lawyers from their duties. Their request mentioned that the defendants could not accept the trial proceedings’ disregard of their rights. It was further explained that the defendants had been subject to trials operated under rules and practices that do not serve to protect their right to a fair trial, which should have been guaranteed under standard legal principles and the spirit of the law. For instance, they did not have the right to consult with their lawyers confidentially. The authorities also imposed strict measures to restrict the interactions between defendants and their lawyers and physically assaulted a lawyer while providing legal counsel for one of the defendants. Defendants’ family members and ordinary citizens were also not permitted to observe many trials in line with the principles of open court and transparency. The defendants and their lawyers have informed the Court about these issues multiple times; however, the Court continuously failed to make improvements.

Later, the defense lawyers filed a letter of complaint to the Director-General of the Criminal Court, raising concerns about their obstacles in the performance of their duties in this case. The letter also urged the Director-General to conduct an investigation and review any relevant measures to ensure they are reasonable and adhere to general principles of standard criminal procedures. The proceedings shall also uphold the open court principle and the fundamental rights guaranteed in a normal judicial process.

10. To be granted bail, defendants must agree during a court hearing to refrain from engaging in activities that could tarnish the monarchy

10. To be granted bail, defendants must agree during a court hearing to refrain from engaging in activities that could tarnish the monarchy

On 5 April 2021, the lawyers filed bail applications for Somyos, Patiwat, and Jatupat. Thus, the Court summonsed the three defendants for a hearing that afternoon. Then, on 9 April 2021, the Court granted bail for Patiwat only while denying bail for Somyos and Jatupat. The bail denial was justified on the grounds that both defendants released the defense lawyers of their duties during the witness examination on 8 April 2021.

This was the first time that the Court granted bail for a defendant indicted under Article 112 in this case. However, the defendant had to declare that he would not be involved in any activities that tarnish the monarchy’s reputation. A credible person must also serve as a guarantor who promised to supervise the defendant to ensure his compliance with this bail condition. Accordingly, the Court decided to authorize bail upon the condition that the defendant “shall not engage in any activities similar to his offense related to the monarchy or be involved in any activities that may tarnish the monarchy’s reputation.”

This process became a normative precedent for requesting bail for the other defendants facing charges under Article 112 in this case and other cases in the Criminal Court, such as the case of Chukiat “Justin” Saengwong, and in other courts, such as the cases of Sirapob “Kanoon” Pumpuengput and Wanwalee “Tee” Thammasattayam, who were tried in the Southern Bangkok Criminal Court, and Piyarat “Toto” Chongthep in the Kalasin Provincial Court. Similar conditions have reportedly been imposed for certain non-Article 112 cases. For example, in the case in which defendants were indicted for allegedly surrounding and blocking a prison van, the defendants were required to promise that they would not participate in demonstrations and follow the Court’s bail conditions.

The bail request hearing has become the Court’s standard procedure for assessing whether to grant bail for the defendants in nowadays’ cases related to freedom of political expression. Previously, it is not a mechanism widely used with defendants in political or other cases. Typically, the Court would only examine the bail requests and supplementary documents to make a decision.

According to Section 107 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the Court shall instantly deliver an order upon the receipt of an application for provisional release. However, the said hearing process causes further delay in the Criminal Court’s decision-making process because the hearing date must be scheduled. It usually takes a few days, and if there are COVID-19-related risks, the Court would not allow the defendants to attend the hearing. Some key examples that clearly demonstrate such a limitation included the cases of Parit, Chai-amorn, and Panupong. It must be acknowledged that the situation of COVID-19 pandemic in detention facilities are truly life-threatening for prisoners. Moreover, Parit’s deteriorating health required urgent medical attention and treatment owing to his long hunger strike, which lasted for more than one month and a half. Nonetheless, while the Court could have chosen to conduct the hearing via video conference, it decided not to pursue that option.