The coup d’état on 22 May 2014 has left greater long-lasting legacies and enduring challenges for the resumption of democratic rule in Thailand than any previous coup over the past few decades. After the junta that launched the coup, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) ruled the country for five years, one month, and 23 days, a general election was finally held nationwide. The new cabinet ministers then took an oath before the king and assumed their positions on 16 July 2019, thus automatically dissolving the NCPO. Nonetheless, the politico-military network of the NCPO and the Royal Thai Army has remained active and has continued to sustain their power through elaborate orchestrations of the design of new political systems, constitutional provisions, and legislative tools.

In addition, the NCPO also deployed various mechanisms that can be characterized as “quasi-laws” or “quasi-judicial proceedings” as weapons for intensively suppressing the political resistance and activism of dissidents. Wielding these weapons, the NCPO initiated many lawsuits to clamp down on political expression and demonstrations. Several cases remain unresolved up until the present. Further, such mechanisms have also been passed on to the new regime during the post-NCPO period. Notably, they have been utilized even more intensively after the #FreeYouth movement launched a series of political rallies from mid-2020 onwards. Therefore, one can say that laws and legal institutions, as critical legacies of the NCPO era, have been fully incorporated as an essential state apparatus for political repression.

On the seventh anniversary of the 22 May 2014 coup d’état, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) would like to revisit the lawsuits linked to political expression during the NCPO regime. In the second part of this analysis, TLHR will assess the outcomes of such cases in which the coup-making body or state officials accused the defendants of committing illegal offenses. A particular emphasis will be placed on cases under key legal provisions used by the NCPO as political weapons. Our analysis will demonstrate that the actual impacts of such legal charges are not only manifested in the cases’ outcomes but also unfold as part of the legal proceedings and serve as instruments for maintaining governmental and political powers.

Read part 1 of the analysis here

Cases under the ban on political gatherings: Equal ratio of dismissal of cases and conviction of defendants who confessed

Several cases stemmed from charges created by the NCPO specifically to suppress public activism and demonstrations. Notably, the NCPO issued Orders No. 7/2557 and No. 3/2558, which banned political gatherings of five or more people. Both orders were in effect for more than four and a half years after the NCPO’s coup d’état and criminalized any demonstrations to counter the coup, criticize the abuse of power by the junta, and other state policies under the NCPO regime.

According to TLHR’s documentation records, at least 428 people were charged under NCPO Orders and Announcements on the ban of political gatherings in 67 cases throughout the period of their enforcement. These cases were also administered by the military courts, leading to significant delays in the legal proceedings.

Seven years later, in 20 cases, the court had dismissed or struck out the charges after the repeal of NCPO Orders and Announcements. Almost every accused person had to bear the burden of fighting their cases over one to four years until their cases ended. One example is the case against activists involved in the “Stolen Election (Vote for the One We Love)” campaign, which lasted for four years until the military court decided to strike out the charge. In this case, the court neither finished examining the witnesses nor delivered any judgment on the defendants’ alleged violations. Throughout the four years, the four defendants were subject to the burden of frequenting the military court regularly.

In total, the public prosecutor ordered non-prosecution in nine cases, mainly owing to the repeal of NCPO Orders. On the contrary, for the case on the “We Walk, Friendship Walk” activity, the civilian prosecutor decided not to indict the accused as the demonstration was considered apolitical. Likewise, the military prosecutor dropped the case against people who allegedly formed the Revolutionary Democratic Alliance Party due to insufficient evidence.

In 23 cases, the defendants pled guilty because the offense does not prescribe a severe penalty. Upon conviction, TLHR found that the verdict mainly put the defendants on probation and suspended the prison sentences. Under this offense, one could face imprisonment lasting from 45 days to four months, with the possibility of probation or a fine ranging from 2,500 to 5,000 baht. Many of the accused did not want to face the long-term burden of fighting their cases. Thus, they chose to plead guilty in the beginning. However, the condition of probation creates fear among the convicted and discourages them from participating in political activities in the future.

There are also seven cases in which the defendants agreed to undergo training to terminate the lawsuits. NCPO Order No. 3/2558 permitted the accused to seek an alternative to imprisonment by attending “training” by military officers to cease the suit. Many ordinary citizens who were not professional activists agreed to this alternative because it was a way to quickly resolve the charges.

Nevertheless, according to the information received, many participants of such trainings were asked to sign a memorandum of understanding to refrain from joining or organizing political activities in the future. This contract became a string attached to the training participants for the rest of their lives. Such a practice reflects how the primary objective of this NCPO Order is to suppress political activity.

Furthermore, in one case, Apichat Pongsawat, the defendant charged for holding up a protest sign at an anti-coup rally in front of the Bangkok Arts and Culture Center, chose to fight the lawsuit. However, the court ended up convicting him. The trial, in this case, was processed in a civilian setting and reached the level of the Supreme Court. Even though the ban on political gatherings had been lifted, the Supreme Court still ruled that he was guilty and sentenced him to pay a fine of 6,000 Baht. The Supreme Court justified its verdict by stating that the NCPO’s decision to lift its ban on political gatherings did not retrospectively impact cases initiated previously. However, this rationale received widespread criticism from the public because it constituted the use of a repealed law to punish the defendant for an action that was no longer designated as a crime.

Meanwhile, even though the NCPO has been dissolved, three cases are still pending decisions because the accused were charged not only under the NCPO Orders but also other laws. Therefore, the authorities have not struck out the cases or dismissed the charges yet. For example, the public prosecutor in the case against the pro-election activists involved in the UN62 rally asked the Attorney General to order non-prosecution because the offense has been revoked. However, such a request was not authorized. Another example is the case of the Khon Kaen Model, which is still pending trial in a civilian court after being transferred from a military court.

In addition, there are four remaining cases in which no progress has been reported. According to statistical data, 29 cases were dismissed/struck out by the court or not indicted by the public prosecutor. Meanwhile, there were 31 cases in which the court convicted the defendants or the accused agreed to attend military training. The number of both kinds of outcomes is, thus, almost equal.

In political cases, even though the court convicted some defendants who pled guilty, that decision does not mean that the defendant willfully admitted to violating the law as alleged. The current judicial system has been designed in a manner that can be easily manipulated, controlled, and intervened in by the military. It also causes the burden to fall on the accused to prove their innocence before the court. Such conditions indirectly force many people in lower socioeconomic classes to plead guilty, albeit unwillingly.

Overall, there was no imprisonment of people under new offenses created by the NCPO. However, the use of accusation of committing these offenses to censor, arrest, threaten, intimidate, and suppress political dissidents posed a key obstacle to organizing public activities and created fear among people who want to be involved in political activism. This tactic helped those in power to gain advantage in the war on controlling political demonstrations throughout the NCPO era.

Cases under Article 112 (lèse majesté): More than half pled guilty, fighting for innocence carried a high cost

Cases of violation of Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code during the NCPO regime were different from the other kinds of cases discussed above because of how the measure was enforced, particularly until 2017. Procedures associated with its enforcement tended to pressure the accused to plead guilty, including detention while awaiting trial, secret trial, broad and vague interpretation of the law, lawsuit against the cases’ contents, high potential penalty, and social pressure. These reasons caused many accused people to plead guilty to received a reduction in the penalty. In addition, during the NCPO regime, military officers threated individuals during detention and interrogation in military camps before prosecution.

According to TLHR’s documentation records, there were 169 people who were charged under Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code after the 2014 coup. Within this the number, at least 106 people were charged in relation to their expression in 90 cases and at least 63 people were charged in relation to deriving benefits from claiming an association with the monarchy. Considering the 90 cases of political expression, it is found that the defendants in 42 cases pled guilty, which is equivalent to 46.7% of the documented cases.

Moreover, there were 15 cases in which defendants tried to defend themselves before the verdict. These were 57 cases or 63.3% of all cases in which the court convicted the defendants.

In addition, the court acquitted in 12 cases, the public prosecutor did not indict in 9 cases, there is ongoing litigation pending verdicts in 5 cases, the status of litigation proceedings is unknown in 6 cases, and the defendant passed away awaiting trial in 1 case.

During the NCPO regime, both the military courts and the civilian courts tended to level a high penalty against defendants convicted of violation of Article 112. The penalty ranged from 5 to 8-10 years per count of violation.

In early 2021, there was a decision in the case of Anchan, who was accused of 29 counts of publishing the voices of “Banphot.” She was initially tried in the Military Court and was detained for almost 4 years before she was released on bail. After the case was transferred to the Criminal Court, she decided to plead guilty. Consequently, she was convicted with violation of Article 112 with the highest imprisonment term to have ever been recorded, which is imprisonment of 87 years. After she pled guilty, the term of imprisonment was reduced to 29 years and 174 months.

In 15 cases, the court chose not to convict the defendants under Article 112 of the Criminal Code but resorted to Article 116 or the CCA. This move began in early 2017 when the policy direction regarding the enforcement of Article 112 gradually shifted. At the time, the police stopped pressing charges under this law, and the court avoided using it to convict defendants. This new trend led to a decrease in the number of new lèse majesté cases. In several instances, the plaintiff used this law to file charges against the defendant, but the court ended up convicting the defendant under a different law not invoked by the plaintiff. At times, the court did not even provide any judgment on the cases’ substances concerning Article 112, such as in the cases of lawyer Prawet Praphanukul, Prathin in Khon Kaen Province, Buppa, and Sichon.

The enforcement of lèse majesté varied over time in accordance with high-level policies. People in power have the ability to adjust the level of penalty, determine the manner of enforcement in different political contexts, and select the target of the enforcement. This trend attests to the political nature of this law.

During the NCPO era, the court eventually dismissed several Article 112.cases, especially those in which the defendants chose to fight the trial. Usually, the court granted bail to the defendants in these cases. The cases were also transferred to civilian courts before the witness examination process and trial were concluded.

One example is the case of Thanakorn, who liked a Facebook page that publishes content deemed as defamatory against the monarchy and posted a message that insulted the King’s pet dog. After five years of legal battle, the Samut Prakarn Provincial Court dismissed this case, explaining that his liking of the Facebook page did not mean he admires the content therein and his post referring to the King’s dog did not constitute an act of defaming the King. In this case, Thanakorn was held in a military camp for seven days and in a remand prison during the police investigation for 84 days. He was released after being indicted. The lawsuit greatly impacted his life. He quit his career and became a monk while fighting the suit from the start in the military court.

In the case of Patnaree, the defendant was accused of committing lèse majesté for responding to a text message deemed as defamatory against the monarchy by saying “Yeah.” Her legal battle took more than four years before the Criminal Court dismissed the case, citing that her response merely aimed to end the conversation and did not signify any agreement with the defamatory message. During the trial period, the defendant was adversely impacted in many areas. She received less work from employers. Her relationships with others deteriorated. Furthermore, she had to live with the fear that arose from the intimidation and harassment from people who threatened to harm her and her son, Sirawith ‘Ja New’ Serithiwat, a prominent political activist during the NCPO era.

Activist Bandit Aneeya was also charged under this law in two cases during the NCPO era for expressing his opinion about the monarchy during the Innovation Party’s forum in 2014 and for expressing his views about constitutional amendments in 2015. His legal battle for both cases lasted approximately five years and nine months and four years and two months, respectively.

Sarawut, an optician and political activist from Chiang Rai Province, was charged for posting a photo of the then Crown Prince with the caption, “His Majesty looks super cool.” The defendant insisted that he did not post this message. The legal battle lasted three years and six months. Eventually, the court dismissed the case because the existing evidence still posed doubts. Sarawut was held in remand for 38 days before he was bailed out to fight the lawsuit.

Natthida ‘Waen’ Meewangpa was charged for sending a message to a Line group. She was detained in prison for over a year before receiving bail. Her legal battle lasted three years and six months. The case was transferred from a military to a civilian court and was eventually dismissed.

Military officers filed charges in most of these cases. It must be noted that the media’s reporting on lèse majesté cases under Article 112 to the public remains limited. Accordingly, there is little public awareness about the persons facing these charges and the allegations that led to the lawsuits. The authorities, in turn, often provide news in an accusatorial tone to de-legitimize and create a burden for the defendants who have to fight the lawsuits. In many cases, the defendants were detained for a long time until they pled guilty. Fighting these lawsuits during the NCPO era, therefore, carried extremely high costs for the defendants.

Overall, lèse majesté and other measures of political repression, such as detention in military facilities and visiting personal homes by state officials, led to the shrinking of civic space for exercising the freedom to express opinions related to the monarchy. As the transition to a new reign occurred during the NCPO regime, the enforcement of these laws and measures were essential for the regime. Remarkably, the ceiling for criticizing the monarchy, or the use of lèse majesté, became even lower than prior to the 2014 coup.

Escalation of lawfare from the NCPO regime to the rise of #FreeYouth demonstrations

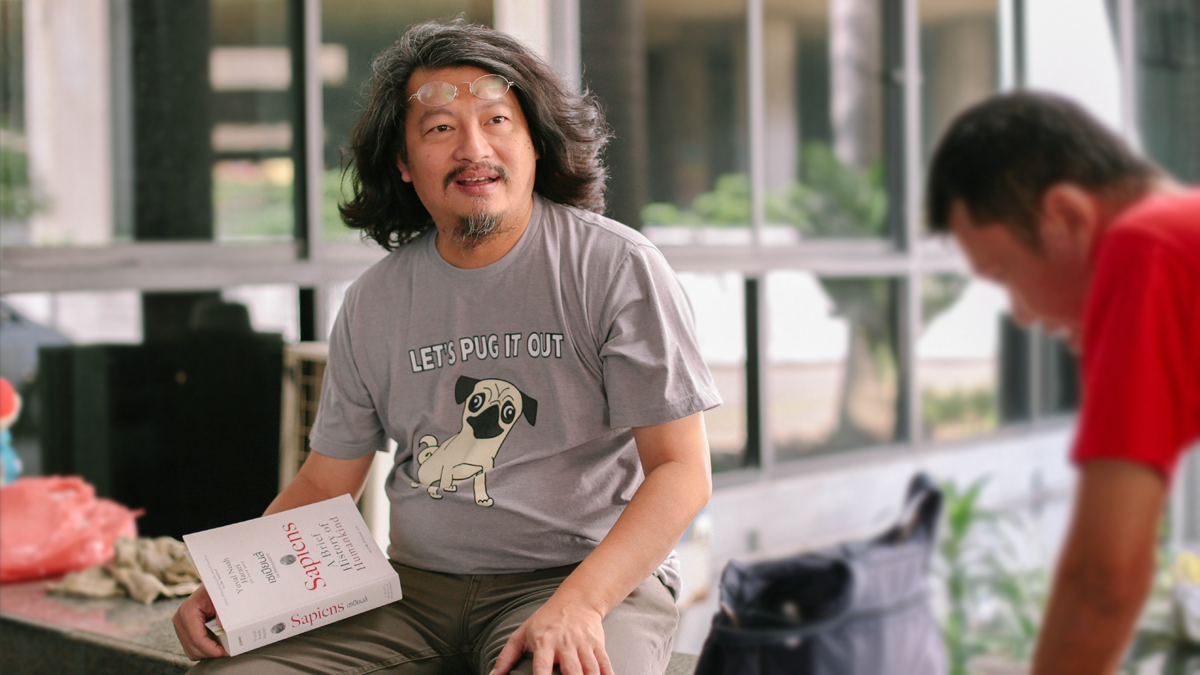

“In my view, I have to agree that NCPO was able to stay in power for five years and could form parliament afterward. It showed that our resistance was not successful. However, I think it needs to be noted in history that there were some groups of people who did not accept the power of the NCPO.”

“The documentation of such political cases will, someday, be a case study. The verdicts will be discussed in relation to the law and political science. I hope it will be that way and it will be recognized in history that they had guns and we had only our voices.”

Sombat Boonngamanong, excerpts from an interview before the verdict hearing in the case of Article 116 (sedition) which he fought for six years

During the nine-month duration of #FreeYouth demonstrations from 18 July 2020 to 30 April 2021, TLHR found that at least 635 people were charged in 301 cases for participating in political gatherings and expressing political opinions.

The number of people charged for their involvement in political activities in 2020 surged to an unprecedented level. The period saw a marked increase in the number of cases, which covered a wide range of geographical areas and impacted people of all ages. Notably, a significant number of minors have been subject to charges for their activism. This phenomenon reflects how lawfare, which utilizes the laws and legal procedures as political weapons, has not ended after the dissolution of the NCPO. It has instead become even more prominent under the new regime.

As the youth became more politically active throughout 2020, they began to organize demonstrations more frequently and brought forth increasingly contentious political demands. Lawfare was intensively deployed as a response to this political awakening. Accordingly, the number of new political cases over the past year could almost match the sum total of all the cases during the NCPO’s five-year era.

Noteworthy is the widespread use of the sedition law to charge many prominent activists and protestors. During the first phase of the pro-democracy movement, the law was used in lieu of Article 112 of the Criminal Code and posed various interpretation issues. At least 103 people were charged under this law over the past nine months, almost equal to the total number of sedition cases initiated during the NCPO’s five-year era.

Even though the government already lifted the NCPO Order banning political gatherings of five or more people, it has turned to impose new restrictions under the Emergency Decree, which contain a more severe penalty, for suppressing political activities across the country. The COVID-19 pandemic has been used as an excuse to enforce such restrictions. Even though no political gathering to date has caused an outbreak, more than 500 people were charged under the Emergency Decree for participating in political rallies over the past year. This number has already surpassed the total number of cases under the NCPO’s ban on political gathering during the junta’s five-year rule.

Shortly after the protesters began raising their demands about monarchical reform, Article 112, previously suspended, was reintroduced. The number of people charged under this law soared at an unprecedented rate. More than 90 persons are charged under this law, which is almost equal to the number of cases initiated during the NCPO’s five-year regime. Some protest leaders who called for monarchical reform face more than ten counts of the charge, whereas ultraroyalist “monarchy protection” groups continues to file charges against people under this law. Often, peaceful protestors face lèse majesté accusations along with other minor charges that carry monetary fines under the Cleanliness Act, Land Transport Act, Controlling Public Advertisement by Sound Amplifier Act, and Communicable Diseases Act. Some protestors face more than ten charges in total, making it seem like they have committed serious crimes.

In certain cases, especially when the defendants decided to fight the cases against them, it remains unclear how much time they will have to spend in the justice process and what outcome will result. Through the state’s lawfare, the accused are usually subject to arrest and detention, bear the burden of fighting the lawsuit, and lose opportunity costs in doing other things in their lives. The state is also expending significant resources in the justice system through its police forces, public prosecutors, courts, and prisons to deal with these cases related to political expression.

While many scholars and activists have discussed various issues with Thailand’s laws and justice system, the 22 May 2014 coup has transformed Thailand’s judicial landscape. Its legacies have turned legal procedures into a tool for systematically maintaining the political status quo. The use of such a tool has become a primary strategy for the Thai state and people in power.

Therefore, both old and new lawsuits from the past seven years should be treated as “eyewitnesses” who can testify about the state’s abuse of power through this strategy. These cases await public investigation and examination. What happened in and through legal procedures shall be thoroughly documented so that the public could together examine and hold accountable those involved in such kinds of lawfare in the future.