The coup d’état on 22 May 2014 has left greater long-lasting legacies and enduring challenges for the resumption of democratic rule in Thailand than any previous coup over the past few decades. After the junta that launched the coup, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) ruled the country for five years, one month, and 23 days, a general election was finally held nationwide. The new cabinet ministers then took an oath before the king and assumed their positions on 16 July 2019, thus automatically dissolving the NCPO. Nonetheless, the politico-military network of the NCPO and the Royal Thai Army has remained active and has continued to sustain their power through elaborate orchestrations of the design of new political systems, constitutional provisions, and legislative tools.

In addition, the NCPO also deployed various mechanisms that can be characterized as “quasi-laws” or “quasi-judicial proceedings” as weapons for intensively suppressing the political resistance and activism of dissidents. Wielding these weapons, the NCPO initiated many lawsuits to clamp down on political expression and demonstrations. Several cases remain unresolved up until the present. Further, such mechanisms have also been passed on to the new regime during the post-NCPO period. Notably, they have been utilized even more intensively after the #FreeYouth movement launched a series of political rallies from mid-2020 onwards. Therefore, one can say that laws and legal institutions, as critical legacies of the NCPO era, have been fully incorporated as an essential state apparatus for political repression.

On the seventh anniversary of the 22 May 2014 coup d’état, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) would like to revisit the lawsuits linked to political expression during the NCPO regime. In this article, TLHR will assess the outcomes of such cases in which the coup-making body or state officials accused the defendants of committing illegal offenses. A particular emphasis will be placed on cases under key legal provisions used by the NCPO as political weapons. Our analysis will demonstrate that the actual impacts of such legal charges are not only manifested in the cases’ outcomes but also unfold as part of the legal proceedings and serve as instruments for maintaining governmental and political powers.

Read part 2 of the analysis here

Deployment of “lawfare” and “strategic lawsuits against public participation” under the NCPO

“During the past three years with groups opposed to the NCPO, we found that when the government filed charges and initiated prosecution in a case, the opposition group continued its movement.Yet the government did not immediately bring additional charges. Therefore, if the government brought additional charges, and brought additional charges every time that the opposition starts their movement, it would pressure the activist leaders, limit the freedom of opposition to the NCPO, and would mitigate the radical nature of the speeches instigating [opposition] …”

“Therefore, the repeated prosecution aims to increase the pressure and impose burdens on activist leaders more than aiming to detain them in prisons. The reason is that this has resulted in Thai and international human rights groups, academics, and media outlets pressuring the government to release them on bail. This negatively affects the government.”

One of the messages in a document submitted as evidence by Major General Burin Thongprapai, the legal representative of the NCPO, in the case of the leaders of “People Want to Vote” at Ratchadamnoen (RDN50)

After the 2014 military coup, the academic and civil society sectors observed the increasing use of laws and legal proceedings as political weapons. In response, they have worked to conceptualize this phenomenon to raise public awareness.

“Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation” or SLAPP suits, was the first concept introduced to the public. It explains a particular form of judicial harassment that arises when a strategic lawsuit against specific individuals is used to terminate, retaliate, threaten, or suppress the exercise of political rights, including the freedom of expression, assembly, and association on any issues related to public affairs. Persons who file SLAPP suits do not aim to win the cases but rather to drain the targets’ resources during legal proceedings and push them to stop exercising their rights and liberties.

“Lawfare” is another concept widely discussed in relation to the NCPO era. It describes the phenomenon in which the state and people in power instrumentalize the law and judicial proceedings to eradicate or suppress political enemies and opponents, instead of using firearms as in conventional wars or other extrajudicial means, such as murder, enforced disappearance, and extrajudicial detention. Lawfare also involves the key tactic of mobilizing the media and popular opinion to discredit the opponents and label them as “enemies” and “outlaws,” which further deteriorates the targets’ capacity to organize and consolidate political opposition. Furthermore, those who utilize lawfare can also claim that their actions are legitimate and authorized by the law.

Both concepts offer similar insights on the current situation of the politicized use of law and legal procedures. Remarkably, both show how the law and legal procedures lost their functions of fostering a just society and became instrumentalized for politico-military purposes in suppressing criticism, opposition movements, expression of dissent, and public participation.

The initiation of lawsuits in this manner is not primarily concerned with whether the cases’ outcomes will lead to a more just society or which side will win the cases. Instead, the lawsuits are used as a strategy or weapon for controlling society; strengthening the positions of those in power; and diminishing, threatening, suppressing, and delaying the movement of political opposition and dissidents through the burdens which stem from their involvement in legal proceedings.

The lawsuits may eventually reach the court, and the different levels of the court may end up dismissing the cases. However, such dismissal typically does not have any effects on the power structure. Meanwhile, those in power still win as they successfully drain the resources and suppress people involved in public activism and political demonstrations, discourage people from making criticism and staging protests, and hindering the growth of opposition movements while the lawsuits are carried out.

From this point of view, the entire supply chain of the justice system has been abused as one of the state’s political instruments. Police officers, public prosecutors, courts, and prisons have been converted into combatants to partake in this ‘war’- be it voluntarily or unconsciously. It also does not matter how each individual perceives this kind of use of power.

During the NCPO era, the authorities used many laws to charge numerous people for exercising their freedom of expression. Such laws included NCPO Orders and Announcements; Thailand’s Criminal Code, especially offenses under Sections 112 and 116; and new legislation passed by the National Legislative Assembly appointed by the coup makers. The enforcement of such laws has been aimed at specific target groups perceived by the state as involved in activism, especially those in the political opposition.

Civilians were also tried before military courts under the Ministry of Defense and experienced significant delays in their legal proceedings due to the courts’ discontinuous appointment schedule. Many of the accused, therefore, faced the burden of fighting their lawsuits for many years. Given this factor, their cases will likely not draw to a close soon, even though the NCPO has already been dissolved.

Documents from the case on the “We Want To Vote” group’s demonstration during the NCPO era demonstrate the mindset of those who filed the lawsuit. Such persons view the case as a strategic use of the law. Their mindset regards legal actions as a means for creating advantages for the government while pressuring and undermining the opposition and hindering dissidents. Thus, many legal actions were initiated as military-politico strategies, not genuine attempts to use legal procedures in accordance with the principles of the rule of law.

It can be summarized that the Thai state from the NCPO era to the present continuously and intensively deploys lawfare to suppress and harass dissidents.

Charges under Article 116: 62% of the cases dismissed by the court or public prosecutors

The sedition offense in Article 116 of the Criminal Code became an important charge for political persecution under the NCPO. Listed in the internal national security section of the Criminal Code, the article is expansive and leaves a great deal open to interpretation. Accordingly, the NCPO has used the charge of sedition against those who expressed their political stance more extensively than any other coup-making entity in Thai history.

According to TLHR’s documentation records, during the period from the 2014 coup d’état to the dissolution of the NCPO, at least 126 people were charged under the sedition offense in 50 cases for their political expression. Seven years later, TLHR found that the court had dismissed 16 cases, including 15 under civilian courts and one under a military court. In ten cases, the public prosecutors ordered a non-indictment; six of these cases were handled by civilian prosecutors and five by military prosecutors. Additionally, the Military Court also struck out one case because it did not meet the required legal elements of the charge.

Moreover, there were four more cases in which the court dismissed sedition charges against the defendants but convicted them under other laws. For instance, in the Federation of Thai States case, the defendants were charged with the provision on membership in a secret, illegal society for their expression of disagreement with Thailand’s current political system.

In 31 cases, the court and public prosecutors determined that the accused did not violate Article 116 of the Criminal Code. Accordingly, the defendants were found not guilty as alleged in more than 62% of sedition cases.

Among the cases where the defendants were found guilty, the defendants pled guilty in three cases (two in civilian courts and one in a military court). In contrast, the defendants in five other cases attempted to fight the case in civilian courts but were still convicted.

In three such cases, the court sentenced the defendants under Article 112 in addition to Article 116 because their alleged violations were linked to political expression about the monarchy. Such a complication posed additional challenges for fighting the lawsuit. Meanwhile, for the cases in which the defendants pled guilty, there was no trial to examine the alleged violations of the law.

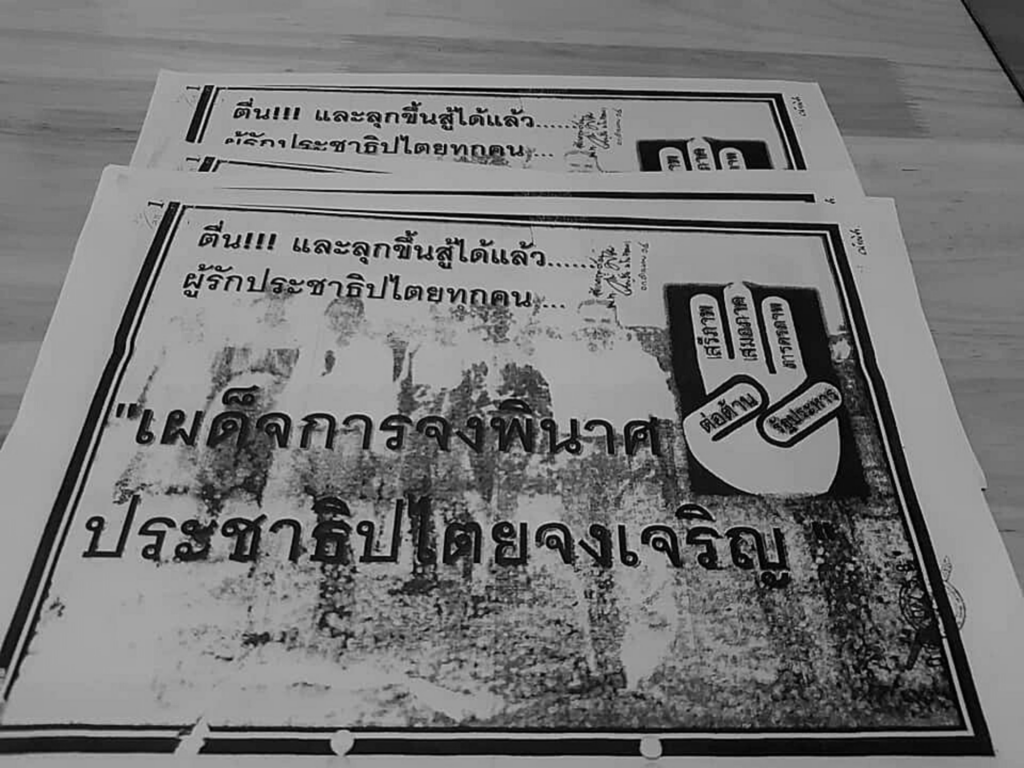

Overall, under the NCPO regime, the court found the defendants guilty in only two cases initiated solely based on a sedition offense. This number accounted for merely 4% of the total cases. Those two cases are the case against Ponlawat, who distributed anti-coup pamphlets in Rayong Province, and the case against three defendants who put up the sign “There is no justice in this country. I want to partition and set up a Lanna state” in Chiang Rai province.

However, the case against Ponlawat is currently pending in the Supreme Court. The verdicts from the Court of First Instance and the Appeal Court have been widely criticized because the rulings affirmed the legitimacy of the coup and the NCPO’s status as a rightful sovereign. Following this logic, the courts determined that disseminating anti-coup pamphlets constituted an act of sedition which triggered public disorder.

Moreover, seven cases are currently pending, and there is no reported progress in the remaining four cases.

The verdicts of many dismissed cases show that the defendants fought the trial for an extended period, especially those whose expression was related to anti-coup activities, because their trials were initially held in military courts with undue delays. Eventually, their cases were transferred to civilian courts after the NCPO’s dissolution. This move allowed the cases to proceed with the process of witness examination and enabled the court to dismiss the cases.

For example, Chaturon Chaisang was charged under this law for hosting a press conference to express his opinions against the coup at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand (FCCT). His legal fight lasted six years, six months, and 26 months from the day he was arrested to the day that the court dismissed his case.

In another case, Sombat Boonngamanong was charged for posting anti-coup messages and inviting people to use the three-finger salute as a symbol to resist the NCPO regime. His legal fight lasted six years, one month, and 26 days from the day he was arrested to the day that the court dismissed his case. During the trials, the NCPO also suspended the bank accounts of Chaturon and Sombat, causing significant difficulties in their daily lives.

Activist Pansak Srithep was also charged for organizing the “Citizen Walk” activity in which he walked by himself to campaign against the trial of civilians before military courts. His legal fight lasted five years, eight months, and 21 days from the day he was arrested to the day that the court dismissed his case.

Another case that significantly impacted the defendant’s rights and freedom was the case against Thanet Anantawong. His alleged violations were linked to his posting and sharing a Facebook post criticizing the NCPO and Royal Thai Army. His legal fight lasted approximately four years and six months. He also spent almost three years and ten months in prison as he was denied bail before the Criminal Court dismissed his case in mid-2020. Therefore, Thanet remained in jail for several years even though he finally was not found guilty on all counts. His father also passed away while he was being detained.

In many cases, the allegations barely checked off the legal elements required by the sedition offense under Article 116. However, the justice apparatus under the NCPO regime still validated such allegations and enabled the cases to proceed despite the absence of appropriate legal grounds.

For example, Chatchawan Kamtai, an independent journalist from Lamphun province, was charged for sending pictures and news about an anti-coup demonstration and providing the wrong date for the event. Even though he only made a minor mistake in news reporting, he ended up spending over a year fighting the lawsuit before the Military Court dismissed the case.

Sedition charges were also filed against individuals who posted photos with a red plastic water bowl in Chiang Mai Province, and politicians from Pheu Thai Party in Nan province, who planned to distribute the red plastic water bowls to the public. These cases made headlines during the trial phase; therefore, the military prosecutors quietly dismissed both cases.

In another case, Preecha, an elderly man who gave flowers to Pansak, who organized the “Citizen Walk” activity, was accused of violating national security laws. While the military prosecutor did not indict him under Article 116 of the Criminal Code, the Military Court still convicted him of violating the NCPO’s Order banning political gatherings of five or more people because he confessed to the crime.

TLHR further observes that many opposition politicians also became targets of the enforcement of Article 116. Apart from the aforementioned cases, many politicians based in northern provinces were charged for submitting a letter to criticize the draft constitution before the national referendum in 2017. These politicians were held in military camps and accused by news outlets of participating in criminal associations to distort the substance of the draft constitution. They were also held in prison for a while. After four years of legal fights, the Chiang Mai Court quietly dismissed all their cases as well.

The NCPO’s legal department also charged the leaders of the Pheu Thai Party for organizing a press conference on the fourth anniversary of the military coup under the theme “Four years of the failures of the government and the NCPO led to darkness and danger.” The legal fight lasted over one year. The civilian public prosecutor decided not to indict the defendants in the end.

Wattana Muangsook faced a similar lawsuit for posting his demand for the government to search for the Khana Ratsadon memorial plaque that went missing. At last, the Criminal Court dismissed this case, stating that his message only constituted a genuine and honest criticism of the government’s work.

This law was further used against participants and leaders of the demonstration of the “We Want To Vote” group in early 2018. Currently, the Court has dismissed two cases, including the cases linked to the protest on the MBK Skywalk (“MBK39”) and the demonstration on Ratchadamnoen Avenue (“RDN50”). The public prosecutor did not file an appeal in these cases. Simultaneously, two other similar cases, including the cases linked to the demonstration in front of the Royal Thai Army complex and the rally in front of the United Nations building (“UN62”), are still in the witness examination phase and remain a burden for activists involved in these cases up until the present.

These cases under the sedition law share a remarkable pattern. A military officer working under the NCPO serves as an accuser in most cases. When the accusation is brought, the NCPO or the Royal Thai Army holds a press conference or provides information to attack the accused and claim that their decision to press charges is in accordance with the “law.” The initiated legal actions also often successfully slow down the momentum of counter-movements or activism work, as seen in the case of the “We Want to Vote” group.

However, when we examined the narratives of allegations in the lawsuits closely alongside existing evidence, we found that the allegations in most cases were greatly exaggerated and aimed to abuse judicial procedure. The long-winding legal battles drained the accused’s resources and created additional burdens for them. In the end, the court has tended to dismiss the cases quietly. In many cases, the court even stated that the accused made genuine criticism and exercised their lawful right to freedom of expression. Despite such dismissals, the defendants have not received any compensation for the losses they suffered while spending multiple years fighting the lawsuits. Moreover, neither the NCPO nor relevant authorities who engaged in the lawfare have been held responsible for their systematic abuse of power.

Cases under the Computer Crimes Act: Majority of cases against opposition politicians, academics, and activists dismissed or not indicted

The Computer Crimes Act (CCA) B.E. 2550 (2008), especially Article 14, is another law continuously used to charge people who have exercised their dissenting political opinions since taking effect. During the NCPO era, the government amended the law into its current version as the CCA B.E. 2560 (2017). Still, the provisions laid out in the amendment continue to provide broad discretion for people in power or the authorities in various government agencies to press charges against anyone who disseminates information or exercises their freedom of expression in online spaces.

According to TLHR’s documentation records, from the 2014 coup d’état to the NCPO’s dissolution, at least 197 people were charged under the CCA in 115 cases for expressing their political opinions online.

In 73 cases, the accused faced another charge- either under Article 112 or Article 116 of the Criminal Code- in tandem with the CCA because their political expressions took place online. Therefore, only 116 people accused in 42 cases faced charges solely under the CCA.

Out of the 116 cases, the public prosecutor decided not to proceed with the indictment in 14 cases. The court also dismissed six more cases. These numbers combined account for 47.6% of the total number of cases under this category.

Meanwhile, the court convicted individuals in seven cases. Among these cases, defendants pleaded guilty in five cases, whereas those in the other two cases fought the lawsuit. The number of cases in which there were convictions account for merely 4.7% of the total cases.

Aside from that, final judgments have not been rendered in four cases and remain pending. There are eleven cases in which there is no reported progress.

Most cases in this category are concerned with expression of opinions regarding the public administration of the NCPO and the abuse of power by state authorities and organizations. The majority of defendants are opposition politicians, academics, and activists who opposed the NCPO and Royal Thai Army.

The Computer Crimes Act has been explicitly weaponized to target political opposition, especially in the cases against leaders of the Future Forward Party and Pheu Thai Party. The NCPO’s legal officers often served as the accusers who filed charges in these cases. TLHR found that the public prosecutor ended up issuing a non-prosecution order for almost every case initiated in this manner. For example, Major General Burin Thongprapai was the NCPO’s representative who filed charges against three executive leaders of Future Forward Party, including Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, who took part in a live broadcasting session that criticized the NCPO’s practice of snatching MPs into their camp. The legal battle lasted more than a year before the public prosecutor issued a final order of non-prosecution.

Piyabutr Saengkanokkul faced a charge filed by Major General Burin for his public reading of a statement criticizing the Constitutional Court’s decision to dissolve Thai Raksa Chart Party. The legal fight lasted for over one year and three months before the public prosecutor issued a final order of non-prosecution.

Lieutenant General Pongsakorn Rodchompoo, a former executive leader of the Future Forward Party, and five other people were charged for sharing a news article with misinformation about General Prawit Wongsuwan’s drinking of expensive coffee. Major General Burin was also the accuser in this case. Later, the public prosecutor ordered a non-prosecution for all of the accused.

Many Pheu Thai Party leaders were charged for posting their opinions online. Wattana Muangsook, for example, was charged under the CCA in at least three cases. The three cases are linked to online posts in which he criticized the court’s verdict in the case of Yingluck Shinawatra’s rice-pledging scheme; condemned General Prayut Chan-o-cha, General Prawit, and the NCPO for refusing to return their powers to the people and using the new constitution to exempt themselves from legal accountability; and denouncing the government for prosecuting people who shared the content of the “KonThaiUK” Facebook page, respectively. The public prosecutor has reportedly issued a non-prosecution order in the first case, while the Criminal Court eventually dismissed the second case. Meanwhile, the third case is currently pending trial.

In a separate case, former Pheu Thai Party Deputy Leader Pichai Naripthaphan was charged under the Computer Crimes Act in at least two cases. The alleged violations were linked to two posts he made: one in which he criticized the NCPO for banning the sales of the Time magazine with Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha on the cover and another in which he criticized the economic policies of the NCPO. Similar to other cases, Major General Burin acted on behalf of the NCPO and filed the charges against the former Pheu Thai executive. Finally, the public prosecutor decided not to indict him in either case.

Apart from the politicians, academics who criticized the NCPO and Royal Thai Army were also targeted. For instance, former dean of Thammasat University Charnvit Kasetsiri was charged by officers from the Technology Crime Suppression Division for sharing a post that criticized the use of handbags by General Prayut’s wife. The legal fight lasted approximately two years. The public prosecutor eventually ordered non-prosecution because his actions did not match the elements required by the provisions laid out in the CCA.

Pinkaew Laungaramsri, an academic from Chiang Mai University, and Hansak Benjasripitak, a a Red Shirt leader in Chiang Mai, faced charges under the CCA for publishing a post that made fun of a fundraising concert organized by the military at the same time that university students held a campaign against the postponement of the general election. A military officer from the 33rd Military Circle filed these charges. It took eight months until the public prosecutor decided to order non-prosecution in both cases.

Activist Ekachai Hongkangwan has been continually accused of violating the CCA in several cases and physically assaulted multiple times when attempting to call for investigation of General Prawit’s luxurious watches. He was charged under the CCA in two cases. The first case stemmed from a Facebook post in which he said that Thailand lost the Thai-Laotian Border War. Major General Burin filed this case against him, and the public prosecutor later dismissed it. In another case, he recounted his personal experiences regarding sexual life in prison. Recently, the Criminal Court found him guilty of violating Article 14(4) of the CCA. He is currently planning to file an appeal against this verdict.

Moreover, in many cases, the authorities have tried to prosecute people who share photos and posts of political Facebook pages which are closely monitored and surveilled by the state. In this type of case, the authorities are often unable to find the page owners who produce the undesirable content. Therefore, they decide to file charges against many people who liked such content instead.

Some of the accused, who were ordinary citizens, decided to plead guilty and confess to the allegations because they did not want to be burdened by lawsuits. Meanwhile, several others chose to fight the cases, which required a significant amount of time and resources. Many of them also reside outside Bangkok and so have had to travel to Bangkok to attend legal procedures. Eventually, the court has dismissed several of these cases.

One example is the case against nine people who shared a post by the “I must have received 100 million baht from Thaksin” Facebook page. The accused were charged under Article 14 (2) of the CCA for sharing the post, which criticizes the NCPO’s drug suppression policies and MP-snatching tactics. Later, seven defendants pled guilty while two others insisted on fighting the lawsuit. The legal battle lasted over a year and a half. The Criminal Court eventually dismissed the case as it could not be proven whether the information in the post was false, and such information did not lead to any harm to national security.

In another instance, ten people have been charged for sharing a post from the “KonThai UK” Facebook page, which said that General Prayut was planning to seek exile because the court would accept to a sedition charge against the prime minister for review. After two years of a legal fight, the court dismissed the cases. Notably, Major General Burin filed the charges in both cases.

Overall, the CCA has been used to silence and hinder people from presenting information or political opinions which run counter to the interests of the NCPO and Army in online spaces. Those who have significant social influence or many followers tended to become more easily targeted by the authorities. In many cases, state officials have regularly surveilled the online activities of specific pages or individuals before initiating legal action against them. Such legal action, in turn, creates a chilling effect that discourages users of online social media platforms from expressing their political opinions.