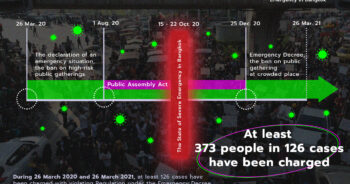

26 March 2022 marks the second-year anniversary since Gen. Prayuth Chan-o-cha, the Prime Minister, has promulgated the Emergency Decree nationwide in response to the outbreak of novel coronavirus (COVID-19). However, this also means that the public assembly, as well as other strong and outspoken political movements, have been under control of the regulations under the Emergency Decree and thus lead to the steepest rise of political lawsuits in Thai history.

According to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, from the enforcement of the Emergency Decree on March 26, 2020, to March 25, 2022, at least 1,447 individuals were accused of breach of the Emergency Decree because of their participation in political rallies which can be counted up to at least 629 lawsuits. Thai Lawyers for Human Rights has drawn several observations from this phenomenon:

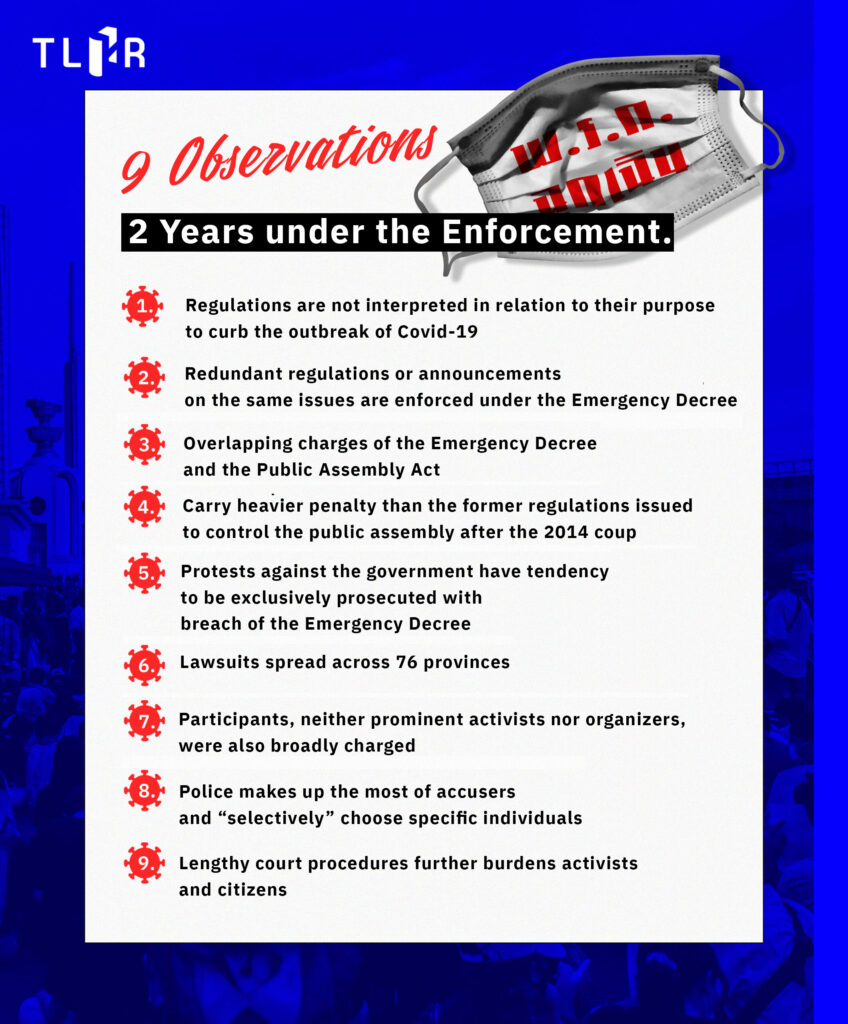

1. Regulations are not interpreted in relation to their purpose to curb the outbreak of Covid-19

Since the outbreak Covid-19, the government has promulgated the Emergency Decree for the prevention of virulent viruses by imposing communicable disease prevention measures such as a restriction on high-risk areas for virus infection, a restriction on certain places as well as prohibition of public assembly and committing any acts that contain high risk of virus infection. Consequently, many redundant regulations on the public assembly have been issued over the past two years under the Emergency Decree.

However, the pandemic did not always stay severe for the entire two-year span. For example, in the middle of 2020, there were several prosecutions under the Emergency Decree among the protestors while no new infections were found in Thailand. The prosecutions went consistently and were not in line with other measurements imposed on other gathering places. For example, the government allowed other festivals and activities as well as other economic activities to resume while the public assembly was strictly controlled under the same measures.

Even protestors who participated in low-risk activities for virus transmission were also prosecuted under the Emergency Decree; participants in “car mob” rallies were charged with “participating in the public assembly which has high risk of infectious disease transmission” and “inciting disorder in the public” despite the fact that they are symbolic movements to show dissent against the mismanagement of the current government by driving vehicles together on one road, turning on the vehicle’s light, blowing horns, and showing three-finger salutes. Up until now, there have been at least 96 lawsuits regarding these causations.

2.Redundant regulations or announcements on the same issues are enforced under the Emergency Decree

Over the past two years, Gen. Prayuth has promulgated 12 regulations regarding the prohibition of public assembly under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree. Even though the content has been changed, redundancy still exists. (See more detail in Thai by iLaw)

Chief of Defense Forces has also issued 15 announcements of the chief official responsible for security in the emergency situation under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree which prescribes the prohibition of public assembly. The content also varies but is still redundant. (See more detail in Thai by iLaw)

Similarly, under the Communicable Disease Act, governors of each province have issued regulations to prohibit activities concerning any gatherings to prevent the outbreak in each province. Moreover, the regulations in each province have been edited back and forth several times. (See more detail in Thai by iLaw)

The redundant issuance of the aforementioned regulations and announcements confuse not only the citizens who are not aware of which regulations or announcements are in effect but also the law enforcement agency, such as police officers. In some cases, police officers repeatedly informed the alleged offenders of the same charges or inform additional charges because they formerly informed them of the charges from the previous regulations that had already been nullified or from the regulations that were not effective at that time.

Many alleged offenders from participating in the public assembly were informed of many redundant charges ranging from the regulations issued by the Prime Minister, the announcements issued by Chief of Defense Forces, to the regulations issued by the governors. Consequently, many lawsuits contain contradictory and overlapping charges.

More importantly, over the past two years, the legitimacy of these regulations and their legislative grounds have yet to be reviewed. Only the Phayao Provincial Court ruled that the announcement of the chief official responsible for security in the emergency situation issued on April 3, 2020, is not legitimate and thus obsolete.

3. Overlapping charges of the Emergency Decree and the Public Assembly Act

Among the number of lawsuits with breach of the Emergency Decree, TLHR recorded that the protestors in at least 41 lawsuits were also charged with the violation of the Public Assembly Act B.E. 2558 (2015) even though Section 3 (6) of the Public Assembly stipulates that the provision shall not be enforced while the Emergency Decree is still in effect. However, police officers still filed both charges and so did prosecutors.

No court decision regarding this legal issue is available up to this point. However, the Thonburi Municipal Court acquitted both the Emergency Decree and the Public Assembly Act charges for the alleged offenders in the lawsuit regarding #2020Dec6Rally because the plaintiff’s evidence could not prove whether they were the organizers of this rally and thus were not guilty as charged.

However, there were also at least 74 lawsuits where police charged protestors only with the violation of the Public Assembly Act during the declaration of the Emergency Decree. Many alleged offenders charged with “failure to notify the authority of the public assembly” agreed to pay fines to end the lawsuits. However, there were 2 lawsuits in Lampoon where, shortly before the witness examination, the prosecutor withdrew the Public Assembly Act charges after the prosecutor had already indicted alleged offenders of the aforesaid allegations. However, the clear reason for this withdrawal was not clarified. (More information on the first case and the second case in Thai)

The enforcement of these overlapping “laws” on public assembly, albeit contradictory to the existing provision, prompts us to closely monitor many lawsuits that are and will be on trial.

4. Carry heavier penalty than the former regulations issued to control the public assembly after the 2014 coup

The penalty of the violation of Section 9 of the Emergency Decree is up to 2-year imprisonment or a fine of 40,000 baht or both. Thus, it carries a heavier penalty than the previous regulations enforced to control the protests; those charged with the violation of the Public Assembly Act B.E. 2558 (2015) most of whom were accused of “being the public assembly’s organizer” face only up to 10,000 baht fine.

Moreover, the Emergency Decree even carries the heavier penalty to the regulations enforced after the 2014 Coup by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO); NCPO Announcement no.7/B.E.2557 (2014) on the prohibition of public assembly stipulates that the penalty shall be up to 1 year imprisonment or 20,000 baht fine. Later when the NCPO Order no. 3/B.E.2558 (2015) was enforced instead, which stipulates that neither gatherings nor political protests of five persons shall be staged at any places, the penalty is only up to 6-month imprisonment or 10,000 baht fine. The difference is that during the NCPO era, the trials of these allegations were tried in the Military Court instead of the Civil Court.

Thus, the regulations enforced to control the public assembly during the outbreak of Covid-19 carry the heavier penalty than the regular time and far heavier than after the 2014 Coup where the public gatherings were strictly controlled.

5. Protests against the government have tendency to be exclusively prosecuted with breach of the Emergency Decree

Among these 629 lawsuits, TLHR found that only one rally in favor of the government and the Thai monarchy was charged with breach of the Emergency Decree which is the rally to support and protect the monarchy by Vocational Students and People’s Network to Protect the Monarchy in front of Bangkok Art and Cultural Center on March 14, 2021. Subsequently, two individuals were charged with breach of the Emergency Decree at Pathumwan Police Station. However, other subsequent gatherings on similar topics were not reportedly prosecuted. Moreover, the strict control over gatherings was exempted for governmental activities; they were not counted as the violation of this decree.

Meanwhile, many lawsuits stemmed from the protests calling for the government to resign, demanding monarchy reform, including other grassroots movements urging the government to take actions on other matters which are not straightforwardly political. These included P-Move group’s rallies, the Chana Rakthin Group’s demonstrations against the Chana industrial project, #SaveBlangkoi group’s demonstrations, “Take Back What Is Ours Not Begging for Donation” group’s gathering calling for better social security (in Thai: กลุ่มขอคืนไม่ได้ขอทาน) and the worker unions’ demonstrations demanding help for the workers.

Thus, it could be said that the Emergency Decree is enforced exclusively for the anti-government movements or any demonstrations opposing the state power, making the “law enforcement” very “political.”

6. Lawsuits spread across 76 provinces

The lawsuits related to public gatherings over the past two years have been spread nationwide, not exclusive to Bangkok or the capital provinces of each region. The trends of the prosecution can be mainly categorized into two waves. The first is the prosecutions which have ensued after the Free Youth rally in July 2020 as many rallies to back up Free Youth’s three demands subsequently took place in various provinces such as Chiangmai, Lampoon, Phayao, Chiangrai, Udonthani, Roi-et, Ubonratchathani, Khon Kaen, Mahasarakham, Samutprakarn, Rayong, and etc.

The latter are the prosecutions stemming from “car mob” rallies calling for Gen. Prayuth Chan-o-cha’s resignation which took place from July 2021 onwards. As more activities were staged in various provinces, police officers subsequently charged protestors sporadically, including in the Southern region where there were no lawsuits regarding this issue on the first wave. TLHR found that during the second wave there were at least 16 lawsuits in 9 provinces. Also, there were lawsuits stemming from “car mob” rallies in Central provinces such as Singhaburi, Nakhon Nayok, Saraburi, Lopburi, and Chachoengsao. (Read the report on the lawsuits regarding car mob rallies in Thai)

These trends show that the enforcement of the Emergency Decree on the dissent movements are “the government policy” leading to nationwide lawsuits. At the same time, it also shows the nationwide political awakening among Thai citizens and youths as political movements arise in the area that might be previously politically inactive.

7. Participants, neither prominent activists nor organizers, were also broadly charged

Another respect in the prosecutions of the public assembly under the Emergency Decree is that police broadly pressed charges on the participants who were neither organizers nor prominent activist leaders; they were charged even though they were randomly on the protest sites or briefly gave a speech on the stage and some were just passers-by.

Due to this treatment, some lawsuits may have many alleged offenders. For instance, thirty individuals (in two lawsuits) were prosecuted for allegedly participating in the Free Youth rally on July 18, 2021; these included one-time participants and even musicians. Thirty-eight individuals were also prosecuted in #ChiangmaiWontBearItAnymore case even though most of them were only participants, not the organizers. Not to mention that 99 individuals were apprehended in the rally by Thalu Fah group. Among them were 6 minors and some were just passers-by. From the crackdown on Chana Rakthin’s gatherings, 37 individuals arrested; 31 were women and many were elders.

Despite the Court and prosecutor’s decision on several cases that alleged offenders were neither entitled to provide Covid-19 prevention measures nor notify the authority of the public assembly, many passers-by and participants were still charged due to these causations.

8. Police makes up the most of accusers and “selectively” choose specific individuals

Among the Emergency Decree lawsuits, it was mostly investigative police officers who made complaints against protestors with the inquiry police officers in charge in the incident areas. Consequently, many alleged offenders were the same persons, especially activists and citizens who had participated in a number of rallies or had prominent roles in the movement. Police closely monitored them, took their photos, and noted down their full name in each rally. In other words, police called them “target persons” so that they could be easily identified. Thus, many activists who participated in a number of rallies have been prosecuted with a large number of the Emergency Decree lawsuits.

On the discretion of the regulations on the prohibition of the public assembly that contains high-risk of Covid-19 transmissions, there were hundreds or even ten thousand of participants in each rally; however, only certain participants were “chosen” to be prosecuted, putting the police’s discretion in doubt.

9. Lengthy court procedures further burdens activists and citizens

Alleged offenders in any criminal cases must carry a burden of proof; it begins right when they need to report themselves at the police station to acknowledge charges according to the summon warrants. Then inquiry police officers will take at least 1 month to gather the evidence and make a discretion whether to forward the report to the prosecutors. If police officers deem the case proper to pursue prosecution, they will also need to bring the alleged offenders to appear before the prosecutors.

No certain time frame is given for prosecutorial discretions whether to present the case to the Court. If prosecutors have yet to indict the alleged offenders, they need to report themselves at the public prosecutor offices approximately once a month until the prosecutorial discretions are reached.

If indicted, the alleged offenders also have the burden to bail and need to appear before the Court in at least three trial appointments: preliminary hearings and evidence examinations, witness examinations, and verdict hearings. This has not included the duration if the case is appealed to the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court.

In conclusion, the procedure takes at least six months for a single criminal case. Some even take two years or more. More importantly, many appointments were postponed due to the Covid-19 outbreak, making the procedure even more lengthy.

Throughout the entire procedure, alleged offenders or defendants have to manage their own time and report themselves according to each appointment as a proof of innocence. In many cases the alleged offenders or defendants who do not live in the province of incidence need to travel to other provinces and thus creates more burden in travel cost and time.

If the Court eventually declares them innocent or the defendants are acquitted of the allegations, time and money spent during the juridical procedure as “the proof of innocence” are the loss that cannot be mended. More importantly, the Thai judicial system has not reportedly enacted any measures to compensate for the loss in the name of “justice.”

These burdens are also a tool to weaken the political movement and further impose more challenges to many activists. In other words, the enforcement of the Emergency Decree is the state’s strategy to silence the people and shut them off from public participation, namely “strategic lawsuits against public participation” or SLAPPs.