The Miracle of “Law”: The Judiciary and the 22 May 2014 Coup

Three Years of the Coup Regime of the National Council for Peace and Order

Although the use of military force was a key factor in fomenting the coup, the coup and the new regime generated by it would have been unable to succeed and govern without the active role of the judiciary.

In order to exercise authority to control society in the modern era, the regime created by the coup must erase the image of totalitarian rule by military leaders and the use of raw power from the barrel of a gun into the exercise of power according to universally-valued “law.” This must be done even though the military dictatorship continues to exercise power arbitrarily, without checks and balances, and with accompanying grave violations of human rights under this “law.”

However, the camouflage of the power of the gun in the form of law and the judiciary system would be impossible without cooperation from the judiciary in creating legitimacy and shoring up the authority of the dictatorship regime.

On the third anniversary of the 22 May 2014 coup, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) assesses the role of the judiciary during the past three years of the junta regime. TLHR begins with examining what “law” means to the junta, next examines how “law” is enforced in the junta regime, and then analyzes the role of the judiciary in the coup and the junta’s exercise of power.

- What is the meaning of “law” for the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)?

“I have said it many times. Law establishes equality among humans in the human world. Everyone must respect the same law, right? If you throw the question back at me, and ask if I have to respect the law. I respect it, right? But I have my own law. I no longer respect ordinary law.”

— General Prayuth Chan-ocha, Head of the NCPO, 29 June 2016

“One day in the future, if we no longer have Article 44 or the NCPO in the future, how will we exist together? And what kind of future will we have? The use of mob rule without respect for law and the judicial process will lead us into the greatest chaos and hardship … The NCPO maintains that we will safeguard the security of the nation and the fair and equal enforcement of the law. We have appropriate standards to create peace and order step-by-step in the country. The aforementioned order [Head of the NCPO Order No. 5/2560, on the Provision of Authority and the Demarcation of a Controlled Area in order to Enhance the Effective Enforcement of the Law in the Area of Wat Phra Thammakai] remains necessary until it is certain that the law can be enforced according to a framework and orders of courts and a judiciary process that are fully correct.”

— General Piyapong Klinphan, NCPO Spokesperson, 27 February 2017

Despite seizing power from an elected government, abrogating the constitution, and violating the fundamental rights and freedoms of the people in violation of law and in grave contravention of a democratic-rule of law regime over the past three years, the NCPO presents themselves as being in compliance with the “law” and requests that the people respect the “law” so that the country may move forward. Those who express dissent or criticism of the NCPO are accused of neither respecting nor following the law.

The question, then, is what does the NCPO use the word “law” to refer to?

Between the 2014 coup and 22 May 2017, the NCPO issued 125 NCPO Announcements, 207 NCPO Orders, and 152 Head of the NCPO Orders under Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution. The “legal servants” of the junta endorsed the legality and constitutionality of these Orders and Announcements in the 2014 Interim Constitution and the 2017 Constitution, even though their content contravenes the values of a democratic-rule of law regime, particularly individual rights and freedoms. These instruments have led to arbitrary detention, torture, disappearance, and the derogation of due process rights.

In addition, the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) appointed by the NCPO has promulgated 239 laws. Many of these laws were passed hastily and contain content that strips the people of their rights and freedoms. In comparison to the Council for Democratic Reform with the King as Head of State (CDRM) that carried out the 19 September 2006 coup, the NCPO has passed a significant number of laws to enforce against the people. The CDRM only issued 34 Announcements and 18 Orders before the 2006 Interim Constitution was promulgated and did not engage in any further exercise of power explicitly outside the law.

- The Enforcement of “Law” After the Coup

What may appear to be “the enforcement of law” and actions in accordance with “the judicial process” have become political instruments of the NCPO to control and prosecute those who have expressed opinions, dissented or criticized the junta during the past three years. TLHR has found that “law” under the junta regime of the NCPO — whether it is an Order or Announcement issued arbitrarily by the NCPO, a law passed by the NCPO-appointed NLA, or other security laws – are enforced by a military-led judicial process directed by soldiers for political purposes against target groups. The combination of “law” and the military-led judicial process have also created exemptions from examination and being held responsible for the exercise of state power for the junta regime.

2.1. The Military-Led Judicial Process and the Constitutional Creation of Exemption from Responsibility

The Orders and Announcements issued by the NCPO have created a “military-led judicial process.” The NCPO controls the entire cycle of the judicial process, beginning with using Orders and Announcements to define certain actions as illegal, placing the examination of violations of Orders and Announcements and other kinds of offences in the military court system, and using martial law and Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558 and No. 13/2559 to detain accused persons in military camps prior to their entrance to the formal judicial process via police authorities at the stage of investigation. In addition, another Head of the NCPO Order provides authority to military officials to participate in the investigation. In cases within the jurisdiction of the military court, military prosecutors make the recommendation of whether or not to prosecute and then military judges adjudicate and issue punishments. Further, there are also civilians who are detained in prisons set up in military bases.

An example of an accusation used widely in the process is that of political assembly of 5 or more persons prohibited by the NCPO Announcement No. 7/2557 and the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558. As of 30 April 2017, there are at least 37 of these cases in which at least 242 individuals are accused or defendants. Although there has been a reduction in the use of prosecution as the regime has remained in power, the Head of the NCPO Order No.3/2558 has also been used to search, seize and detain individuals on military bases without warrants in order to control and suppress individuals who have become targets or to prevent actions viewed as undesirable by the NCPO from occurring.

Simultaneously, the junta regime’s legal system has placed the NCPO Orders and Announcements and Head of the NCPO Orders, including actions or the exercise of power under these instruments, beyond examination or audit. The entirety of actions of the NCPO and officials, which are illegitimate under the ordinary legal system, do not have to be accounted for under the junta regime’s legal system.

The Interim Constitution of 2014 enacted by the legal servants of the junta endorsed the military-led judicial process via Articles 44 and Article 47 which stipulate that NCPO Orders and Announcements and the Head of the NCPO Orders, including actions taken following these Orders and Announcement, are legal, constitutional and final, irrespective of their executive, legal or judicial force, and irrespective of whether they were undertaken before or after the constitution was promulgated.

In addition, Article 48 of the 2014 Interim Constitution stipulates that all of the members of the NCPO and individuals involved in the coup are “exempted from offences and all accountabilities” arising from their actions.

These conditions remain in the 2017 Constitution. Article 265, paragraph 2, stipulates that during the NCPO retains the authority and duties accorded to them in the 2014 Interim Constitution during the period between the promulgation of the 2017 Constitution and the first general election. Provisions of the 2014 Interim Constitution pertaining to the power of the Head of the NCPO and the NCPO remain in force.

Further, Article 279 of the 2017 Constitution stipulates that the exercise of power and all of the actions of the Head of the NCPO and the NCPO, irrespective of their executive, legal or judicial force, and irrespective of whether they were undertaken before or after the constitution was promulgated, and which remain in force according to Article 265, paragraph 2, are all legal and constitutional under the 2017 Constitution and will remain constitutionally in force.[1]

This means that General Prayuth Chan-ocha and the junta remain able to exercise their power according to the 2014 Interim Constitution as well as those accorded to them in the 2017 Constitution as well without any provision for checks and balances or accountability.

Therefore, the exercise of power according to the “law” and various actions that have taken place in the name of “law” under the NCPO’s legal system since the 22 May 2014 coup have been deemed permanently “legal” even though they are in contravention to the law, conflict with the constitution in a normal democratic-rule of law regime, and have led to the grave violation of human rights.

These conditions have created ongoing impacts during the past three years. All of the actions of the NCPO and state officials in accordance with the Orders and Announcements of the NCPO and the Head of the NCPO Orders exist above accountability for any harm that arises in the past, present and future. The NCPO is able to arbitrarily exercise power that results in executive, legislative, judicial and constitutional effects in contravention to the principles of checks and balances in democratic-rule of law regimes. Further, these conditions create a vacuum in which the rights and freedoms of the people disappear, despite being stipulated as constitutionally guaranteed; in practice, rights and freedoms are subject to exceptions and are resultantly without an effect. Those directly affected by the junta’s exercise of power are dispossessed of the right to contest, protest, or make demands in the Civil, Criminal and Administrative Courts.

2.2 The Enforcement of Existing Law Under the Junta Regime

Existing law, particularly laws related to the monarchy and national security, continue to be used in parallel with the NCPO Announcements and Orders and Head of the NCPO Orders. Existing laws are used as instruments to control society, suppress opposition political groups and impede the expression of opinions and other forms of political expression. This is done by the expansive interpretation of law, increases in punishment, the placement of cases within the jurisdiction of the military court system, the use of legal accusations as political threats, etc.

Article 112 of the Criminal Code

Following the 19 September 2006 coup, there was a marked increase in the use of Article 112 of the Criminal Code (lèse–majesté), which is the accusation of defaming, insulting or threatening the king, queen, heir-apparent or regent. The use of the law further escalated after the 22 May 2014 coup. After the death of King Bhumipol Adulyadej on 13 October 2016, the heightened use of the law was also accompanied by conflicts among citizens over the expression of opinions about the institution of the monarchy and a series of witch-hunts.[2]

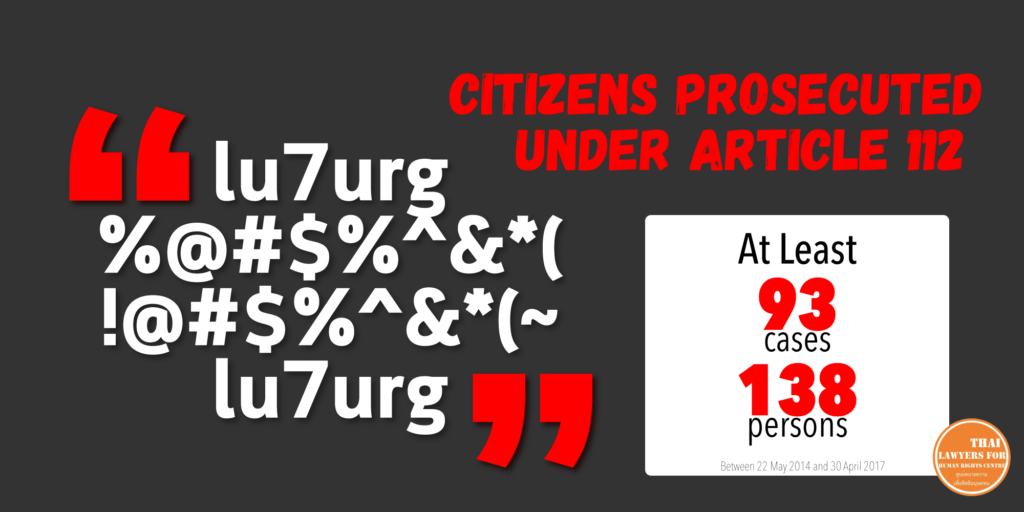

TLHR found that as of 30 April 2017, there are at least 93 Article 112 cases in which at least 138 individuals are accused or defendants.

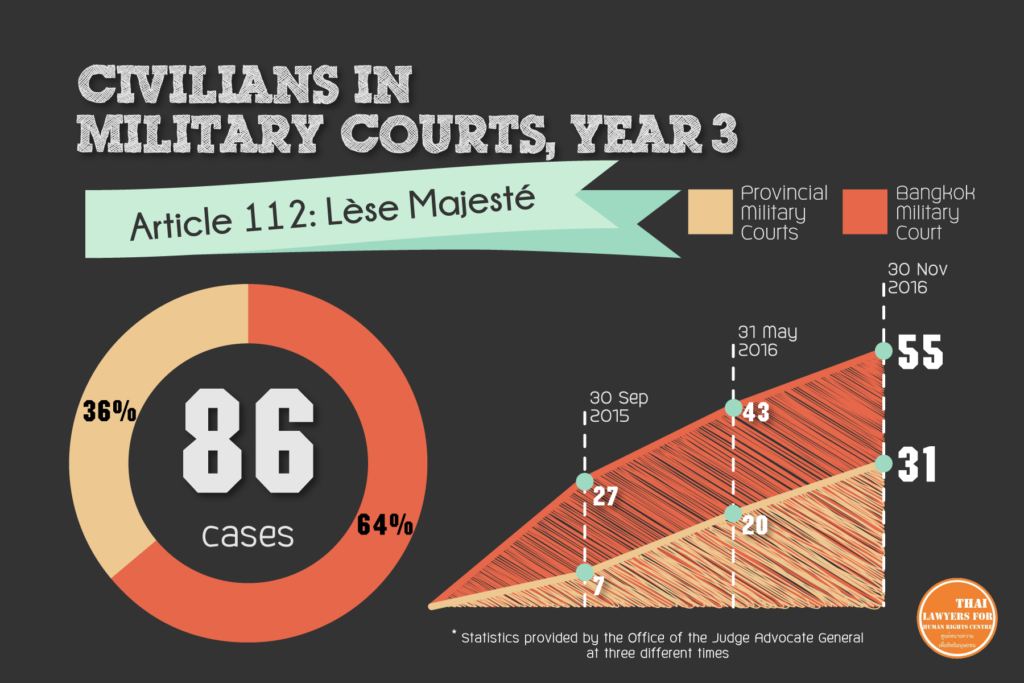

Information provided by the Office of the Judge Advocate General instead indicates that stipulates that between 25 May 2014 and 30 November 2016, there were a total of 86 Article 112 cases in the military court system: 55 cases in the Bangkok Military Court and 31 cases in provincial military courts.[3]

The interpretation of Article 112 expanded greatly after the 2014 coup. The law has been extended to prosecutions in the following kinds of cases: those who clicked “like” or “share” on Facebook, even when they did not write the post in question; those who did not forbid or condemn others who expressed opinions that fell within the scope of violation of Article 112; those who made satirical posts about the pets of the monarch; the expression of opinions about King Naresuan and Princess Sirindthorn, who are not figures named in Article 112; and those who made references to the institution of the monarchy to seek profit for themselves. The law was expanded to cover these cases even though these actions are not delimited as offences in Article 112.

A new phenomenon emerged after the king’s death in which state officials attempted to surveil the internet to locate those who clicked “like” or “follow” on the Facebook pages of those with a role in expressing opinions about the institution of the monarchy; state officials were interested in these people even though they did not express any specific opinions.[4]

Article 116 of the Criminal Code (Sedition)

Before the 2014 coup, Article 116 of the Criminal Code, or the offence against state security in the kingdom, or sedition, was an article that was rarely used.[5]

After the 2014 coup, this law became one of the primary tools used by state officials to suppress the political expression of the people. The meaning of sedition was expanded to include peaceful public expression of criticism of the NCPO, political campaigns, opposition to unjust laws, and protesting and opposing the state on other matters. All of these actions were cast as agitation intended to foster insubordination among the people. The meaning of state security in the law was reinterpreted to mean the security of the NCPO government, the junta and the military.

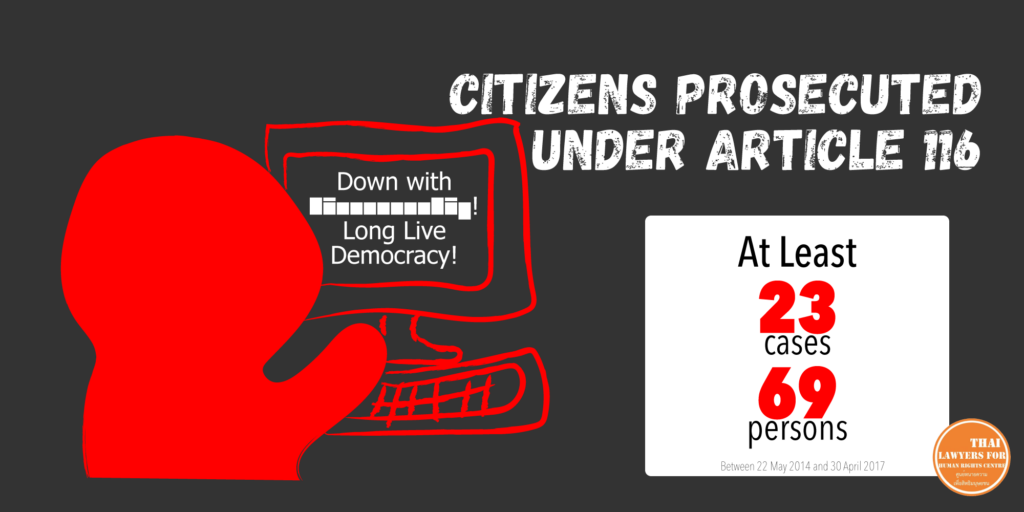

As of 30 April 2017, there are at least 23 cases involving at least 69 people being prosecuted for violation of Article 116. Nearly all of the accusations are related to peaceful political expression or expression of opinion. Some cases involve the ridicule of those who hold power. None of the cases include instigation to cause violence.

Those charged with violation of Article 116 include the following individuals and following alleged crimes: Chaturon Chaisaeng, traveling to be a speaker about the impact of the coup at the Foreign Correspondent’s Club; Sombat Boonngamanong, posting that he did not accept the coup on Facebook on Twitter; Pansak Srithep, engaging in a walk to oppose the trial of civilians in the military court; Preecha, giving flowers to Pansak during his walk; Rinda Pornsiriphitak[6], posting a rumor about General Prayuth; Mrs. Chayapa, posting a rumor about a countercoup on Facebook; Thanakorn, for copying and sharing to Facebook a chart about corruption in the construction of Rajabhakti Park; Thanet Anantawong, sharing to Facebook a chart about corruption in the construction of Rajabkakti Park; eight Facebook page administrators for making a Facebook page called “We Love General Prayuth”; those who distributed flyers opposing the NCPO at the Democracy monument; and those who sent letters criticizing the draft constitution.

Computer Crimes

The enforcement of the 2007 Computer Crimes Act (CCA) has been beset with problems. This has especially been the case with the use of Article 14 (1), which stipulates that action “that involves import to a computer system of forged computer data, either in whole or in part, or false computer data, in a manner that is likely to cause damage to that third party or the public” is a crime and which has been used in many defamation cases. The situation worsened following the 2014 coup as the military became the direct partner in conflict with a large number of people. The CCA has become an important tool used to control and suppress those who express criticism or views contrary to those of the military online. The military officials who bring the cases often claim that online criticism has resulted in harm to individuals or the NCPO.

Those charged with violation of the CCA include the following individuals and following alleged crimes: Maitri Chanroensuksakul, a Lahu activist, posting a comment to Facebook noting that military officials slapped many villagers in the face (the Chiang Mai provincial court dismissed the case at the beginning of 2016); Watana Muangsook, posting criticism to Facebook of an interview given by General Prawit Wongsuwan, commenting on soldiers following and photographing Yingluck Shinawatra, and generally criticizing the situation of the country under the NCPO (the Bangkok Criminal Court dismissed the case at the end of 2016); Buriboon Kiangwarangkul, a red shirt leader from Bang Pong, posting criticism to Facebook of searches under Article 44 by police officials; and Wira Somkhwamkit, posting a survey about opinions concerning the NCPO to his personal Facebook page.

2.3 Laws Enacted by the National Legislative Assembly

After the 2014 coup, the Head of the NCPO appointed members of the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) to serve in lieu of the Parliament and Senate. A large number of the members of the NLA are soldiers and it is therefore disconnected from the people. The process of enacting laws has been accelerated and the NLA operates as a “rubber stamp assembly” for the junta without a process of checks and balances.

Under these conditions, many of the laws enacted by the NLA contain content that limits the rights and freedom of the people. Along with NCPO Orders and Announcements, these laws are used to control social movements and suppress those who oppose the coup. One example is the 2015 Public Assembly Act, which came into force in August 2015. This act does not stipulate that political assembly of 5 or more persons is forbidden, but stipulates that the organizer must inform the authorities about the assembly at least 24 hours in advance. The organizer must inform the head of the police station in the area where they will assemble of the day, time, location, and purpose of the assembly.

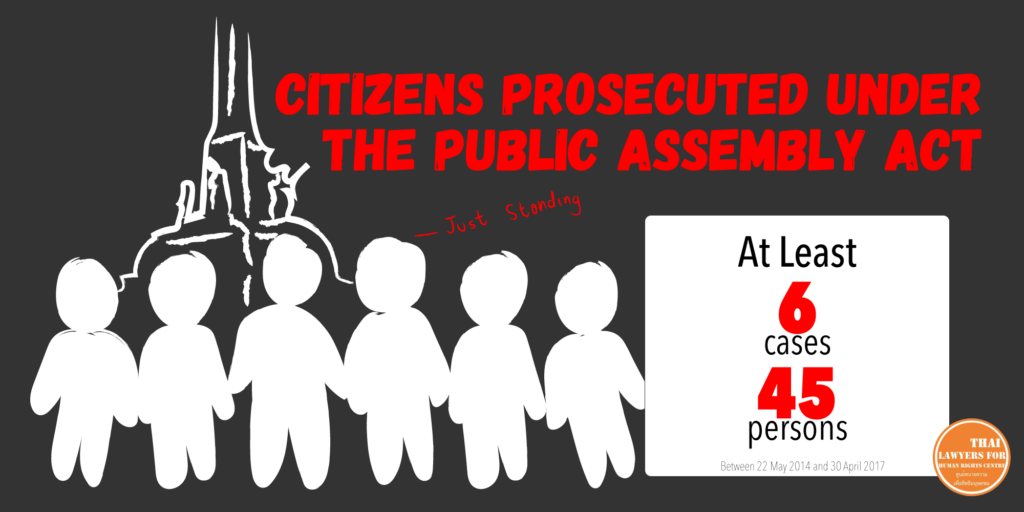

After the passage of the 2015 Public Assembly Act, organizers of protests and political activities were indicted and prosecuted for not informing the authorities about the assemblies at least 24 hours in advance. There are at least 6 cases involving at least 45 accused persons. Instances of demonstrations in which organizers face prosecution or have been prosecuted include: protest in opposition to the movement of the Khon Kaen Transportation Terminal; “Simply Standing” protest to call for the release of Watana Muangsook by Resistant Citizen at the Victory Monument; protest outside a TAO (a subdistrict administrative organization) assembly meeting by Khon Rak Baan Kerd villagers who oppose a gold mine in Loei province; protest by villagers in Phichit province against the transport of minerals by a gold mining company; and a demonstration in the form of a procession to prolong the life of water sources in the area affected by a potash mine in Sakhon Nakhon province.

Even though the 2015 Public Assembly Act provides measures to control and limit political demonstrations, there are still instances in which state officials also use the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558, on the preservation of peace, order and national security, to prohibit political demonstrations of 5 or more persons. This is the case even though, according to principles of law, new laws typically nullify previously-existing laws and special acts supersede general law. Therefore, although the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558 has not been explicitly revoked, the passage of the 2015 Public Assembly Act, which does not stipulate prohibition of matters on which protests can be carried out, should constitute a removal of prohibition on public political assemblies.

The simultaneous use of the Head of the NCPO Order and the 2015 Public Assembly Act results in confusion about the enforcement of law. There have been cases in which organizers sent letters informing the relevant police commander about a public assembly, but then officials cited the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558 to detain the organizers, such as in the case of the demonstration against the construction of a coal-fired power plant in Krabi in front of Government House on 18 February 2017.

The 2016 Referendum Act, especially Article 61 (1), paragraph two, is another law which has been used extensively to deprive citizens of rights and freedoms. A large number of citizens who peacefully expressed opinions in the period prior to the referendum on the draft constitution have been prosecuted or are facing prosecuting under this law. Article 61 (1) is problematic both due to its broad and ambiguous phrasing as well as its stipulation of a harsh and disproportionate punishment of up to 10 years of imprisonment and a fine of up to 200,000 baht. The law was used to suppress the expression of opinions about the draft constitution of by a wide range of people in society.

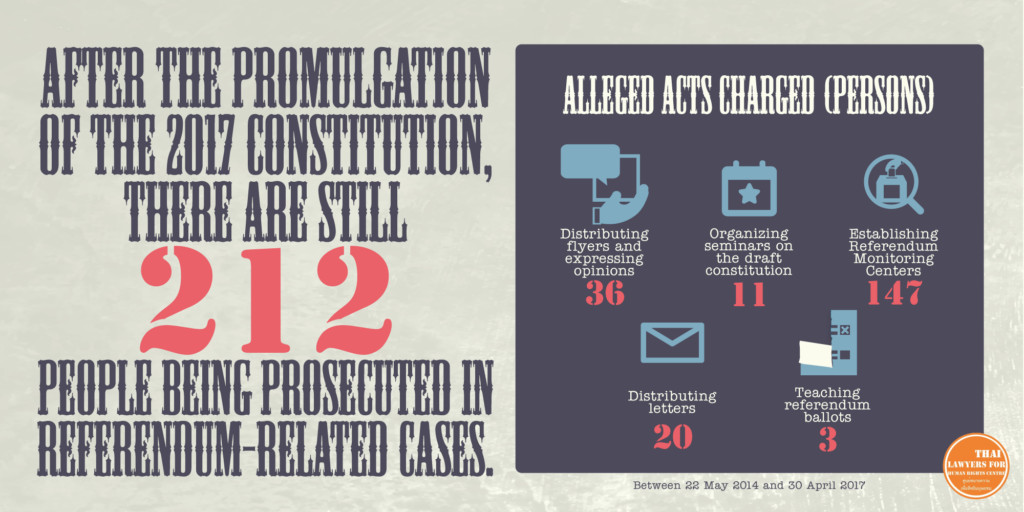

According to information collected by TLHR, there are at least 212 people who have been prosecuted under a range of laws for expressing their opinions on the draft constitution.[7] This includes at least 51 cases under the 2016 Referendum Act, of which 38 cases remain in process in the military and civilian criminal courts.

During the past three years, the various kinds of “law” noted above have been constructed and enforced together in order to create an image of Thailand as a state which retains the rule of law, or which is governed by a legal system, even though the content and enforcement of the “law” violate the rights and freedoms of the people and are designed to control the junta’s target political groups. Significantly, this situation could not arise and be maintained solely through the power that comes from the barrel of the gun, but necessarily relies on the workings of the judiciary as well.

- The Judiciary and the 22 May 2014 Coup

After the 22 May 2014, the civilian judiciary, including the Courts of Justice, the Administrative Court, and the Constitutional Court, became involved in supporting the junta through carrying out trials, issuing orders and rulings, and making decisions and setting punishments. This has effectively supported the existence of the coup regime by generating legitimacy for the NCPO’s legal system and exercise of authority.

TLHR separates the role of the judiciary following the 22 May 2014 coup into two distinct aspects: proactive and negative.

The proactive role includes the performance of these actions:

- The endorsement of the coup and the legal status of the junta;

- The ruling of the NCPO Announcements and Orders are part of the legal system;

- Support of the military-led judicial process;

- Revocation of the rights of the people to oppose the junta; and

- Support of the suppression of individuals and groups targeted by the junta.

The negative role is constituted by the refusal to examine or rule on the legality or other legitimacy of the actions of the junta and other state officials following NCPO Announcements and Orders.

3.1. The Proactive Role of the Judiciary

3.1.1. The judiciary participates in the endorsement of the coup and the revocation of the rights of the people to oppose the coup.

Previously, Supreme Court Decision No. 45/2496 endorsed the coup of 8 November 1947 by stipulating that, “The facts indicate that the junta succeeded in seizing the governing power of the country in 1947. The junta had the authority to change, amend, and pass laws according to the system set up by the coup in order to rule the country. Otherwise, the country would be unable to be peaceful. Therefore, the Interim Constitution of 1947 is a valid law.”

This decision then became the prototype used as a basis for courts to rule to legitimate coups in subsequent periods.

Although there is not yet a Supreme Court decision about the 2014 coup, this pattern can be seen in a decision made in the case of Sombat Boonngamanong, who was prosecuted for not reporting himself to the NCPO. During his defense, he made the argument that the NCPO seized the power to rule illegally. He further noted that at the time he was summoned, it was not yet clear whether or not the coup had succeeded because neither had the king counter-signed the coup nor was the official announcement printed in the Royal Thai Government Gazette. However, in Appeal Court Verdict No. 7767/2559, the Appeal Court noted that, “The facts show that it was a successful seizure of power. The National Council for Peace and Order is a sovereign … [regarding the reference to there must be a royal command first] would result in an odd impact and there would have been a problem in controlling and preserving the peace and order in the country. Further, it would not be appropriate as this would infringe upon the institution of the monarchy by mandating that the monarchy be involved in endorsing whether or not the coup was successful. The success of the coup must be determined from the facts at the moment when the power was seized.”

However, it does not appear that the court cited any facts to support the view that the coup was successful. In addition, Sombat argued that he was innocent because his action not to report himself was done with reasonable cause as he had the right to resist the NCPO Orders and Announcements of the NCPO and to protect the 2007 Constitution. The Appeal Court’s view was that, “The seizure of power of the National Council for Peace and Order was completed successfully and the NCPO has the status of being the sovereign that exercises state power. The defendant cited the 2007 Constitution as his justification for opposing the National Council for Peace and Order, but it has been revoked, and therefore cannot be used as justification. The defendant is therefore guilty as charged by the plaintiff.”

In addition to the Appeal Court endorsing the sovereign power of the junta, they therefore also ruled to revoke the rights of the people to oppose the coup and the seizure of power by illegal means as stipulated in the Constitution.[8] Unless the courts act to protect the rights of the people in a democratic-rule of law regime, they will not become real.

3.1.2. The Judiciary’s Role in Supporting the Military-Led Judicial Process

The NCPO Announcements No. 37/2557, No.38/2557 and No.50/2557 stipulate that from 25 May 2014, 4 kinds of criminal offences were to be adjudicated in the military court system: offences against the monarchy, offences against state security, offences defined in NCPO Announcements and Orders, and weapons offences. In addition, martial law was in force from 20 May 2014 until 1 April 2015, at which time many of its provisions were replaced by the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558. This resulted in the creation of a military-led judicial process, in which the military was in control of arrest and detention, investigation, prosecution and the rendering of the judgment, the stage of investigation, the stage of prosecution, up until when the judgment was issued. This amounted to total and complete military control of the judicial process without the possibility of any external audit or examination.

The military-led judicial process is an important instrument of the NCPO in controlling and suppressing individuals and groups that oppose the coup or criticize the NCPO’s rule. Accused persons and defendants face significant difficulties in accessing the right to a fair trial and searching for justice. Further, the military-led judicial process serves as an example to threaten other individuals in society and to cause them to be afraid to take action or engage in other expression that may impact the NCPO.[9]

The military-led judicial process has been able to proceed because it receives support from the civilian court system. That is to say, when a civilian holds the view that her case should not be examined by the military court, she can submit a petition disputing the jurisdiction between the courts. Then, both courts, the Court of Justice and the military court, must issue opinions regarding their views on this dispute. If both courts arrive at the same opinion, the case will be examined in the military court. But if the two courts disagree, the case will be examined by the Committee to Rule on the Jurisdiction Between Courts.

During the past three years, at least 15 defendants in the military court have attempted to use this channel to submit petitions both on whether or not the use of the military court is unconstitutional and to dispute the jurisdiction between the courts.[10] But the Court of Justice has issued opinions confirming that the NCPO Announcements Nos. 37/2557, 38/2557 and 50/2557 carry the status of law and are legal, and maintain that the military court has the authority to examine and rule in these cases.

For example, the activists who were accused of violating the junta’s ban on political gatherings of 5 or more persons for taking a train to investigate corruption at Rajabhakti Park submitted a petition arguing that their cases were in the jurisdiction of the civilian court rather than the military court. They argued that the NCPO Announcement under which they were accused did not have the status of law and the NCPO Announcement prescribing the prosecution of civilians in the military court system was in contravention to Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), as prosecution by the military lacks independence, impartiality, and there is no possibility to appeal to a higher court. But the Talingchan District Court, a civilian court, held that when the NCPO seized the ruling power and became the sovereign, they had the power to promulgate law, which included the power to issue various Announcements and Orders. This, together with Article 47 of the 2014 Interim Constitution, which endorses all of the NCPO Announcements and Orders to be in force until they are amended or revoked, demonstrates the legality of the prosecution of civilians in the military court system.

Defendants in the Rajabhakti Park Corruption Investigation Case Submit a Petition Disputing the Jurisdiction of the Military Court

The defendants then argued that although the NCPO Announcement No. 37/2557 placed cases of violation of NCPO Announcements and Orders within the jurisdiction of the military court, the plaintiffs’ accusation was that they violated the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558 and was therefore not covered. However, the Talingchan District Court ruled that the Head of the NCPO issued Order No. 3/2558 in line with Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution of 2014, which stipulates that the Head of the NCPO has the authority to issue orders with the consent of the NCPO and when the action has been taken and is reported to the Chair of the NLA and the Prime Minister. This means that the Head of the NCPO does not issue orders on his own and that the Head of the NCPO Orders are held to be NCPO Orders issued by the Head of the NCPO. Therefore, the case remained within the jurisdiction of the military court. This is a case in which the court went beyond the text of the law in its interpretation in order to support the use of the military court.[11]

Pansak Srithep, accused of violating the NCPO Announcement No. 7/2557 and Article 116 for his walk in opposition of the prosecution of civilians in the military court, submitted a petition disputing the jurisdiction of the court on the basis that he was a civilian and not a soldier. He further argued that his actions were legal, constitutional, and peaceful and that the NCPO Announcements did not possess the status of law. The Criminal Court ruled that his case was in the jurisdiction of the military court and further legitimized the junta’s exercise of power as follows:

“When the NCPO successfully seized the ruling power of the country, the Head of the NCPO was then afforded the power to issue Announcements or Orders that were held to be law that can be enforced on the people … Thailand is a state party of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and Article 4 stipulates that state parties are able to avoid their obligations under Article 14 in times of public emergency, including the promulgation of martial law. In these cases, the state party must inform the other state parties of this derogation by presenting the matter to the United Nations. In this case, Thailand’s permanent representative to the United Nations in New York in the United States took a letter to the United Nations Secretariat to inform them of the promulgation of martial law from 3 a.m. on 20 May 2014 … Article 47 [of the 2014 Interim Constitution] stipulates that all of the NCPO Announcements and Orders and Head of the NCPO Orders announced between 22 May 2014 and when the Cabinet takes office are in force. Therefore, the NCPO Announcement Nos. 7/2557, 37/2557 and 38/2557 are in force.”[12]

Pansak Srithep or ‘Nong Cher’s Father’ Disputes the Jurisdiction of the Court in the Case of Walking for Justice

3.1.3. The Civilian Courts Enforce Junta Orders and Announcements as Law

Some cases involving accusations of violation of NCPO Announcements and Orders are examined in the civilian courts, namely those committed outside the period during which the NCPO placed certain kinds of civilian cases in the military court system (25 May 2014 – 16 September 2016). These include, for example, the violation of the summons to report to the NCPO by Sombat Boonngamanong and Chaturon Chaisaeng and the violations of the prohibition on political assembly during protests in front of the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) by Wirayuth Khongkhanathan and Apichat Pongsawat.

In two of the cases in which decisions have already been rendered, those of Sombat Boonngamanong in the Dusit District Court and Wirayuth Khongkhanathan in the Pathumwan District Court, the court’s decisions accept the NCPO Announcements and Orders as one part of the legal system. They have ruled that the defendants’ actions are crimes, even though their actions of not report reporting to a military junta summons and protesting the coup, would not be considered crimes in a society ruled by a democratic-rule of law regime

The civilian courts have played a clear role in endorsing the validity of the coup and the legal system constructed by the junta. This has facilitated the junta’s rule of the country in the name of “law.”

3.1.4. The Role of the Civilian Courts in the Enforcement of Law Against the Junta’s Targets

The Head of the NCPO Order No. 55/2559 halted the initiation of some new kinds of cases in which civilian are the offenders in the military court system from 12 September 2016. However, this does not mean that the control and suppression of those who oppose the coup or criticize the NCPO, including those viewed by the state as a danger to security, via the “judicial process” has ceased.

For example, Piya, the former stockbroker, was judged guilty and sentenced to 8 years of imprisonment for one violation of lèse–majesté under Article 112 of the Criminal Code and Article 14 of the 2007 Computer Crimes Act in October 2016 by the Criminal Court. In addition, the court read the decision in secret and refused to grant permission to his lawyer to photocopy the decision. This was the case even though the Criminal Procedure Code allows the defendant to make a copy of the documents involved in the court’s examination and stipulates that decisions should be read in open court. This is Piya’s second Article 112 case; in the first case, the Criminal Court sentenced him to 9-year imprisonment, but reduced it to 6 years.

It is worth noting that prior to the 2014 coup, the Criminal Court typically meted out sentences of 5 years of imprisonment per count in Article 112 cases. But after the coup, Piya’s case was the first in which a defendant pled non-guilty and the court sentenced him to imprisonment at a rate similar to that by the military court, in which the majority of cases have resulted in sentences of 10-year imprisonment per count. This demonstrates the heavy punishments that result in cases in which defendants contest Article 112 accusations, whether in the military or civilian courts. The impact of the increase in length of punishment has been to dampen defendants’ hopes of contesting cases.

Another Article 112 case that illustrates the role of the civilian courts in enforcing the “law” against the junta’s targets is that of ‘Pai Dao Din,’ or Jatupat Boonpattararaksa, a student and activist who performs an important role in opposing the coup. He has been accused of violating Article 112 for disseminating a BBC Thai news story about Rama X. Even though his Article 112 case is not being examined in the military court, many of his basic rights have been violated. The Khon Kaen Provincial Court revoked his bail and provided a reason for doing so that lacked a legal basis. The court claimed that his behavior “mocked the officials” and “mocked state power” and therefore he has been held for over seven months (as of July 2017).

Members of Dao Din Outside the Khon Kaen Provincial Court Calling for the Release on Bail of ‘Pai Dao Din’

In addition, 7 activists who organized an activity to provide encouragement and call for the Khon Kaen Provincial Court to release Jatupat on bail were accused of contempt of court because they allegedly acted improperly in the area of the court. This is an instance of the court using ambiguous reasoning and a broad interpretation of the law.

Therefore, even though cases have been moved out of the jurisdiction of the military court system back into the civilian court system, there has not been an improvement in the impact and trends of the enforcement of law.

3.1.5 The Impact of the Judiciary’s Endorsement of the Legality of Complicated Political Points on the Junta’s Political Policies

The judiciary has used legal processes to rule on delicate political matters faced by the NCPO, and in so doing, assisted in reducing the degree of societal friction towards the NCPO.

An important example of this phenomenon is the treatment of the draft constitution after the coup which was subject to a referendum by the people. The referendum was a vulnerable moment for the coup regime because if a majority of citizens voted against the junta’s draft constitution, this would also amount to vote against the legitimacy of the junta itself. Simultaneously, the NCPO had to refrain from using force to limit the peoples’ right to participate in the discussion about the draft constitution as this would impact the legitimacy of the draft.

The Constitutional Court took on a role in the arbitration of various problems that emerged both prior and subsequent to the referendum via Rulings No. 4/2559, No.6/2559 and No. 7/2559.

In Ruling No. 4/2559, the Constitutional Court stipulated that Article 61 of the 2016 Referendum Act, which used broad and ambiguous language to define violations of the Act, was not in contravention to Article 4 of the 2014 Interim Constitution that protects the rights and freedoms of the people to express opinions.[13] The Constitutional Court gave the bizarre explanation that,

“This referendum is one to frame the new constitution. Therefore, it is different from a referendum to amend or change provisions of the constitution. Participating in a referendum is one part of a representative political system. Political campaigning in the period before a referendum is an important step and the duty of state organizations is to simply serve as intermediaries by letting each side mobilize voices equally.”

“The holding of a referendum to frame the new constitution is a mechanism that takes place in the process of constructing a new constitution, after the previous constitution has ceased to be in force. This form of referendum appears in situations in countries which have experienced internal political conflict that caused the political system to collapse and the country to come under the control of a temporary government. Then, such a referendum is organized under an interim constitution or equivalent law. The referendum is therefore one part of the process of putting a new constitution in place to replace the constitution that is no longer in force. State organizations have a role in controlling and managing the referendum, including determining the important questions and points, carrying out campaigns to disseminate information, and determining the rules for the referendum. The referendum set up under the 2014 Amended Interim Constitution (Version 2, 2016) is a comparable one.”

In other words, the Constitutional Court endorsed the holding of a referendum on the new constitution after the junta tore up the old constitution. The referendum was neither free nor fair, as one in a representative political system would be. The referendum was held under the junta’s rule and the junta was therefore about to control the referendum. The Constitutional Court further ruled that Article 61, paragraph 2 of the Referendum Act limited freedom of expression only to the degree necessary to protect the security of the state, peace and order, and the good morals of the people. The Court ruled that the Act was necessary to protect the rights and freedoms of those eligible to vote in the referendum and had no significant impact on individual freedom of expression.

This ruling aided in endorsing the limitation of the rights and freedom of expression of those who did not accept the NCPO’s draft constitution and constructed legitimacy for the process of holding a referendum under the strict leadership and control of the NCPO.

Subsequently, when measures were added to the NCPO’s draft constitutional and the supplementary questions which created a pathway for the appointed senators to vote along with the representatives to select the prime minister during the first 5 years (beginning from the date when Parliament is first formed following the general election). It was the duty of the Constitutional Court, according to the Amended 2014 Interim Constitution, to rule on whether the additional measures added by the Constitutional Drafting Committee (CDC) following the referendum, were legitimate. Significantly, the Constitutional Court Ruling No. 6/2559 allowed the CDC to make an amendment to allow the senators to propose the exclusion of names of candidates for prime minister proposed by the political parties and to increase the power of the senators in creating a pathway for an unelected “external prime minister.”

Subsequently, the Constitutional Court issued Ruling No.7/2559 which stipulated that the preface of the draft constitution passed in the referendum could be amended as King Bhumipol Adulyadej passed away before he signed it. The view of the Constitutional Court was that in a democratic regime with the king as head of state, the constitution was not complete until the king signed it and it was published in the Royal Thai Government Gazette and the preface could therefore be amended by the CDC. It is worth observing that in addition to resolving the problem that arises when the king passes away while waiting for him to sign the constitution, the aforementioned ruling also indicated that the completeness of the constitution is defined by the consent of the king rather than the referendum and endorsement of the people. Therefore, an opening exit for the legal amendment of a draft constitution on which a referendum has already been held.

However, the facts indicate that the amendment of the draft constitution was not only limited to the preface. There were 7 articles amended across the general provisions, provisions on the king, and provisions on the prime minister. Following the king’s order regarding matters that had to be amended according to the royal prerogative, the NLA amended the 2014 Interim Constitution to allow such amendment.

3.2. The Negative Role of the Judiciary

In the coup regime, the judiciary takes a negative role when it refuses or otherwise does not examine or investigate the content of various actions of the NCPO or the exercise of power by state officials that are disputed by those whose rights are violated by the aforementioned actions. This deprives the people of guarantees on their rights and freedoms and is equivalent to lacking an organization that provides checks and balances on the executive or legislative in line with the separation of powers and the protection of rights and freedom of the people in a democratic-rule of law regime.

3.2.1 The Exclusion of Examination of Offences Arising from the Coup

On 22 May 2015, the 1-year anniversary of the coup, the activist group Resistant Citizen was the plaintiff in a case brought in the Criminal Court accusing General Prayuth Chan-ocha and other individuals in the NCPO of violation of Articles 113 and 114 by conspiring to commit a rebellion, subvert the constitution, and overthrow the legislative, executive and judicial authorities through the use of injurious force. On 29 May 2015, the Criminal Court dismissed the case on the basis that it lacked legal grounds. The court ruled that although the seizure of power and actions of the defendants was not in line with a democratic regime, Article 48 of the 2014 Interim Constitution delimited these actions as not constituting offences and the members of the NCPO as being excluded from any liability. Therefore, the entirety of the actions of the five accused defendants are not offences and they are not liable for them. Resistant Citizen subsequently appealed the decision, but the Appeal Court dismissed the appeal without examination for the same reason as the Criminal Court. However, the Appeal Court viewed the plaintiff’s claim that the means by which the 2014 Interim Constitution was promulgated was incorrect and therefore the provisions to provide amnesty to the NCPO are unlawful as a separate point to be examined individually.[14] This point is currently being examined by the Supreme Court.

3.2.2. The Omission of Examination of Wrongdoing Arising from the Exercise of Power Under Article 44 of the Interim Constitution

The Courts of Justice go beyond Article 48 of the 2014 Interim Constitution in their endorsement of the omission of wrongdoing and liability of the NCPO. TLHR has found that the Criminal Court has failed to examine the exercise of power to detain individuals under the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558, which was issued according to Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution. This has occurred in two cases in which petitions were submitted according to Article 90 of the Criminal Procedure Code for the court to examine instances of illegal detention, namely the case of Thanet Anantawong and the case of the 8 administrators of the “We Love General Prayuth” webpage. In both cases, the individuals involved were detained by military authorities for more than 48 hours without a warrant and without being informed of the accusation or the place of detention.

In both of these cases, the Criminal Court ruled that the military officials have the authority to detain individuals under the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558. Therefore, the aforementioned detention is not arbitrary or illegal. Details of the identities of the involved officials and whether or not the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2558 was used were not provided.[15] This omission of careful examination makes it possible for military officials to cite the authority provided by the Head of the NCPO Order to detain people for up to 7 days without anyone being able to investigate.

The omission of examination of the exercise of power according to Article 44 of the Interim Constitution has also occurred in the Administrative Court. For example, Central Administrative Court Order No. 1938/2558, which was an order not to accept a case of a private contractor who experienced hardship from the Head of the NCPO Order No. 24/2558 on illegal fishing. The view of the Administrative Court was when the order was issued according to Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution, the order was prescribed as legal, constitutional and final, and therefore did not require examination by the Administrative Court.

In addition, there is also the case brought by the Network of People in Eight Provinces, along with ENLAWTHAI Foundation (EnLAW), petitioning the Supreme Administrative Court to revoke the Head of the NCPO Order No. 4/2559 on the suspension of the enforcement of city and town planning laws for certain undertakings. But the Supreme Administrative Court issued Order Fo. So. 8/2559 declining the petition. The ruling noted that even though the Head of the NCPO Order No.4/2559 has the status of a law issued by the Cabinet or with the consent of the cabinet and is therefore within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Administrative Court, as it is a Head of the NCPO Order, based on the authority provided by Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution, it is legal, constitutional, and final. The Supreme Administrative Court therefore declined to examine it.

3.2.3. The Exemption of Examination of NCPO Announcements and Orders Following Article 47 of the Interim Constitution

Similar to the cases of Head of the NCPO Orders issued following Article 44, the courts have refused to examine the NCPO Announcements and Orders issued previously. For example, the case of Watana Muangsook, a Pheu Thai Party politician, who challenged the NCPO Announcement No. 21/2557, which banned 155 persons, including himself, from traveling outside the kingdom without permission from the NCPO. The Administrative Court issued an order not to accept the case and Watana appealed to the Supreme Administrative Court. But then the Supreme Administrative Court issued Order No. 617/2559 on 26 November 2015 not to accept the petition. The Court provided the reason that Article 47 of the 2014 Interim Constitution provided that all of the actions, announcements and orders of the NCPO between 22 May 2014 and when a new cabinet takes office are legal, constitutional and final

- Conclusion: The Judiciary and the Power of the Gun in the Junta Regime

The various roles of the judiciary in the three years following the 22 May 2014 coup clearly indicate that the coup, including the construction and functioning of the coup regime, cannot only rely on the power of the gun, but also needs the judiciary to work in tandem with the military power. The judiciary is needed in order to endorse and support the junta’s authority and the junta regime’s legal system.

The impact of the orders, rulings, and decisions of the judiciary, including the Courts of Justice, the Administrative Court, and the Constitutional Court is to shore up the rule of the NCPO by placing it under a cloak that goes by the name of “law” and “the judicial process.” The National Council for Peace and Order operates with complete impunity by using dictatorial power to exempt itself from examination. In truth, the “law” of the junta regime has severe defects in content and its enforcement and the broad exercise of power by the dictatorship impact the rights and freedoms of a large number of the people. None of the courts have examined the legality or constitutionality of the NCPO Announcements and Orders and the Head of the NCPO Orders, including the actions following these Announcements and Orders. These measures are in conflict with the principles of the rule of law and the principles of the separation of powers and they render the provisions of the highest law in the land, which should protect the rights and freedoms of the people, without force. A peculiar legal system has been created in which the judiciary’s only duty is to examine the exercise of power by the [former] elected executive and legislative officials, while there is no examination of the exercise of power that arises from the coup.

Without a transformation of the judiciary to adhere to a rule of law system in which the rights and freedom of the people are protected, there cannot be a transition to a democratic regime in Thailand. Such a transition must also include the removal of the military from politics and the construction of principles which truly places the sovereignty with the people anew.

.

.

.

[1] See TLHR, “Old Powers in the New Constitution: The Status of the NCPO and the Effects of the Exercise of Power Under the 2017 Constitution” [“อำนาจเก่าในรัฐธรรมนูญใหม่: สถานะของ คสช. และผลจากการใช้อำนาจภายใต้รัฐธรรมนูญ 2560”], 7 April 2560 [2017], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=3942.

[2] See TLHR, “1 Month After the King’s Death: An Assessment of the Conflict and Article 112 Prosecutions” [“1 เดือนหลังการสวรรคต: ประมวลสถานการณ์ความขัดแย้งและการดำเนินคดีมาตรา 112”], 15 November 2559 [2017], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=2754.

[3] See TLHR, “Civilians Still Being Prosecuted in the Military Court: Statistics of Civilians in the Military Court, Year 3” [“พลเรือนยังคงขึ้นศาลทหาร: เปิดสถิติคดีพลเรือนในศาลทหาร ปีที่ 3”], 7 February 2560 [2017], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=3498.

[4] See TLHR, “Special Report: When State Officials Surveil You for Clicking ‘Like’ or ‘Follow’ on Facebook” [“รายงานพิเศษ: เมื่อคนกดไลค์-กดฟอลโลว์เฟซบุ๊กถูกเจ้าหน้าที่ติดตามตัว”], 28 December 2559 [2016], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=3133.

[5] Article 116 stipulates that, “Whoever makes an appearance to the public by words, writings or any other means which is not an act within the purpose of the Constitution or for expressing an honest opinion or criticism in order: (1) To bring about a change in the Laws of the Country or the Government by the use of force or violence; (2) To raise unrest and disaffection amongst the people in a manner likely to cause disturbance in the country; or (3) To cause the people to transgress the laws of the Country, shall be punished with imprisonment not exceeding seven years..”

[6] Following the issuance of the prosecution order in Rinda’s case, the military court ruled that the case did not fall within the purview of Article 116 and the charge was dropped. However, as Article 116 is a violation of national security, Rinda was arrested from her home and then detained on a military base before being taken to the military court to be remanded. She was detained in the Central Women’s Prison for many days prior to being released.

[7] See TLHR, “The New Constitution Has Been Promulgated But More Than 104 ‘Referendum Defendants’ Are Still Being Prosecuted” [“รัฐธรรมนูญใหม่ประกาศใช้แต่ ‘ผู้ต้องหาประชามติ’ กว่า 104 ราย ยังถูกดำเนินคดี”], 7 April 2560 [2017], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=3924.

[8] Section 69 of the 2007 Constitution stipulates that, “A person shall have the right to resist peacefully an act committed for the acquisition of the power to rule the country by a means which is not in accordance with the modes provided in this Constitution.”

[9] See TLHR’s report on the second anniversary of the coup, “The Force of the Gun Camouflaged as Law and a Justice System,” 2 August 2016, https://tlhr2014.com/?p=1443.

[10] See TLHR, “Summary of Civilian Struggles to Refuse Prosecution in the Military Court” [“บทสรุปการต่อสู้ของพลเรือนที่ไม่ยอมขึ้นศาลทหาร”], 26 February 2560 [2017], https://tlhr2014.com/?p=3563.

[11] See Talingchan Court, Opinion No. Kho. 7/2559, 20 September 2559 [2016].

[12] See Criminal Court, Opinion No. 1/2559, 29 January 2559 [2016].

[13] Article 61 stipulates that, “Anyone who disseminates text, pictures or sounds that are inconsistent with the truth or in a violent, aggressive, rude, inciting or threatening manner aimed at preventing a voter from casting a ballot or vote in any direction or to not vote is considered to be a figure who creates chaos in order for the referendum to proceed in a disorderly fashion.”

[14] Appeal Court Decision, Black Case No. 2196/2558, Red Case No. 18002/2558, 23 November 2558 [2015].

[15] See Criminal Court Order on the matter of Request for Release from Illegal Detention, Black Case No. 99/2558, Red Case No. So. 99/2558, 17 December 2558 [2015]; Appeal Court Decision on the matter of Request for Release from Illegal Detention, Black Case No. 2350/2559, Red Case No. 16241/2559, 31 October 2559 [2016].