3 July 2021 marks the first day that “car mob” activities have been conducted. Entitled #SombatTour, the first car mob was initiated as a political expression by Sombat Boonngamanong, aka Bor Gor Lai Jud. The activities started from the Democracy Monument and moved towards to the House of Government, calling for the resignation of Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha, the Prime Minister. A few months later, similar activities continued to be conducted and became widespread in various provinces nationwide.

Even though the activities have not reached its ultimate goal, the phenomenon represented a widespread movement stretching across multiple provinces, drawing a large number of participants. It also occurred amid the Covid-19 pandemic, which poses challenges and limitations to organise any assemblies. Coming up with a way for all involved to protest collectively while sitting in a personal comfort of their own vehicles was a significant alternative to express their political opinions.

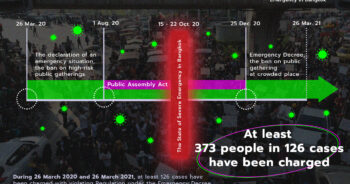

Following these activities in various provinces, the police started to charge participants, mostly with the violations of the Emergency Decree. Legal prosecution has become a “state policy” used against political activists. One year on, a large number of cases are still ongoing, imposing heavy legal burden on these activists despite a recent trend of non-indictment and dismissal by the public prosecutors and the courts, respectively.

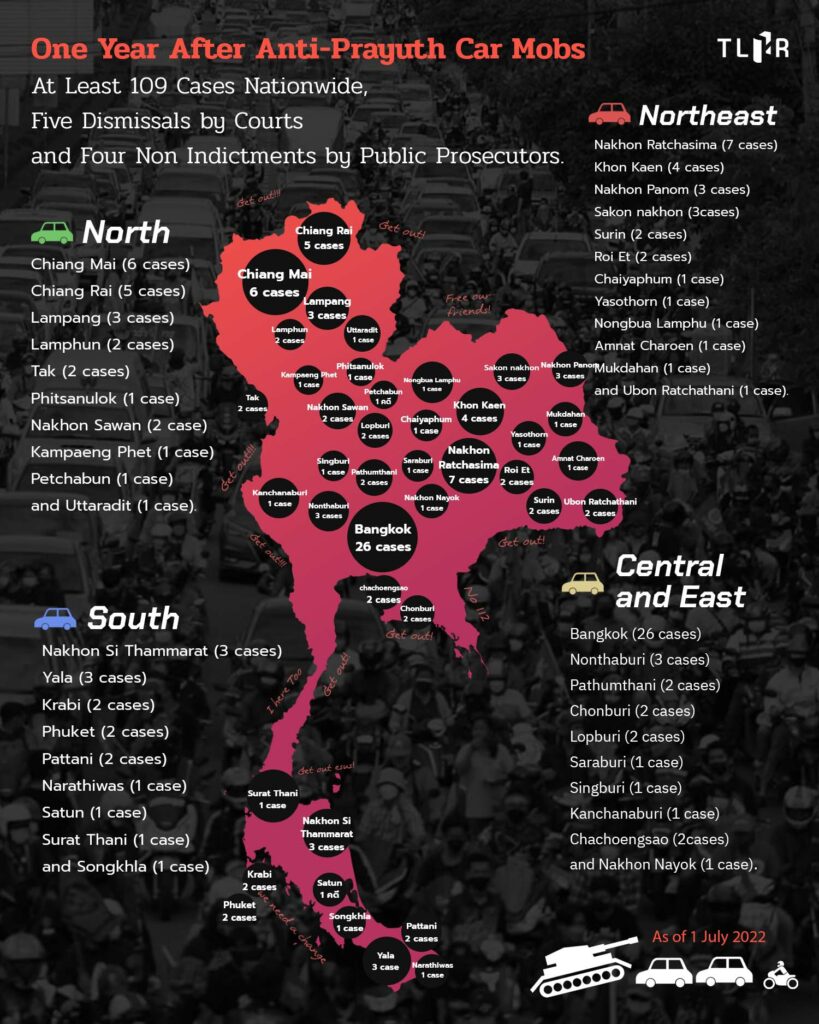

As monitored by the TLHR, at least 269 individuals in 109 cases (some were involved in multiple cases) have been accused after participating in the car mob activities since the beginning of July 2021. Among this number were 21 youths.

Geographically speaking, it was found that the cases occurred in at least 41 provinces in all regions of the country, accounting for 53% or more than half of all the provinces in Thailand:

Central and Eastern Provinces: Bangkok (26 cases), Nonthaburi (3 cases), Pathumthani (2 cases), Chonburi (2 cases), Lopburi (2 cases), Chachoengsao (2 cases), Saraburi (1 case), Singburi (1 case), Kanchanaburi (1 case), Nakhon Nayok (1 case).

Northern Provinces: Chiang Mai (6 cases), Chiang Rai (5 cases), Lampang (3 cases), Lamphun (2 cases), Tak (2 cases), Nakhon Sawan (2 cases), Phitsanulok (1 case), Kamphaeng Phet (1 case), Uttaradit (1 case), Phetchabun (1 case).

Northeastern Provinces: Nakhon Ratchasima (7 cases), Khon Kaen (4 cases), Nakhon Panom (3 cases), Sakon Nakhon (3 cases), Surin (2 cases), Roi Et (2 cases), Ubon Ratchathani (2 cases), Chaiyaphum (1 case), Yasothon (1 case), Nongbua Lamphu (1 case), Amnat Charoen (1 case), Mukdahan (1 case).

Southern Provinces: Nakhon Si Thammarat (3 cases), Yala (3 cases), Krabi (2 cases), Phuket (2 cases), Pattani (2 cases), Narathiwas (1 case), Satun (1 case), Surat Thani (1 case), Songkhla (1 case).

No fewer than 83 cases are currently in the litigation process, while others have not been indicted by public prosecutors or have been dismissed by the courts.

It is to be noted, however, that not every car mob activity eventually led to a lawsuit. Several activities that happened in a similar manner did not end up in a prosecution. In some areas, the police chose to use charges containing a fine penalty instead of the violations of the Emergency Decree, demonstrating double standards and inconsistent implementation of the law.

Of the 109 abovementioned cases, 14 cases have been concluded where defendants are ordered to pay fines based on comparable offences of a prohibited use of amplifiers or under the Land Traffic Act.

Meanwhile, in three Emergency Decree cases (Lampang, Chaiyaphum, and Nongbua Lamphu), the defendants made a confession before the court. The Court has either given a jail term with suspended punishment or suspended the determination of punishment. (In the cases in Nakhon Ratchasima, some defendants confessed, while others insisted on defending the case.)

In four Emergency Decree cases, the public prosecutors decided against the indictment, including the case in Tak, the case in Mukdahan, the car mob case from Don Mueang Airport on 1 August 2021, and the car mob case led by vocational students on 15 August 2021.

In addition, five cases were dismissed by the courts, including two car mob cases in Lopburi, two car mob cases in Nakhon Ratchasima, and the car mob case in Kamphaeng Phet. So far, there has not been any car mob case that led to a litigation where the defendant was found guilty of violating the Emergency Decree by the court.

In conclusion, as of June 2022, at least 83 car mob cases are still on going – 53 are on the investigation stage and 30 are on trial in the court of law. With that, the later half of 2022 will see recurrent rounds of witness examination in various car mob cases from different provinces.

See table >>> สถิติคดี พ.ร.ก.ฉุกเฉินฯ ที่ศาลยกฟ้อง-อัยการสั่งไม่ฟ้อง

Decision patterns of public prosecutors and courts: car mob activities did not contain risks of virus transmission and were regarded as a constitutional right.

The overall patterns regarding the non-indictment/dismissal decisions by public prosecutors and courts in these cases can be summarized below:

1. Many individuals who were prosecuted argued that they were merely participants, and not organizers, and that the prosecutions were targeted at specific individuals, even though there were a large number of participants. The evidences presented by the police officers failed to prove that the accused or defendants were in fact the organizer of the event. Since the public prosecutors or the courts could not verify the organizer status of the accused/defendants, thus, these individuals were neither obliged to obtain permission to organize the activities, nor provide Covid-19 preventive measures. Therefore, the cases were not indicted or were dismissed as a result.

At the same time, some court decisions did not link the posting an online invitation as operating as an organizer. The definition of “organizer” under Section 4 of the Public Assembly Act B.E. 2558 could not be applied during the period following the announcement of the emergency situation.

2. An assembly took place in a short period of time and at a well-ventilated open space. Although there were some gatherings, it was not crowded. Both participants and police officers were able to move around comfortably, and most participants wear medical masks. Therefore, such an assembly cannot be considered as risky of disease transmission. Similarly, an assembly that involves maneuvering cars and motorbikes on the street cannot be regarded as an assembly in a crowded space as vehicles naturally maintain space between them. As such this does not constitute a risk of transmission neither.

The courts that have passed such a decision were of the opinion that the offences under the Emergency Decree must be interpreted based on the intention of the law, which is to curb the spread of the disease. Intimate gatherings did happen but only in some areas of the assemblies, and even then, such gatherings were not crowded, and thus could not be interpreted to be in the scope of the offence. This is comparable to risks associated with a daily life in a household, where family members are found being closely together under the same roof without masks for a prolonged period.

3. A peaceful assembly with speeches criticizing the government is an exercise of a constitutional right to scrutinize the performance of government in a democratic regime. It is not regarded as an instigation of unrest that violates the Emergency Decree.

Despite certain inconveniences caused by the car mob activities, the activities by no means pose an impediment to public traffic in a way that affects traffic safety.

4. The court decisions in some cases have specified that the announcement of the head responsible for solving the emergency situations related to security matters (meaning the commander in chief by position) on the prohibition of public assemblies, activities, and gatherings that trigger the spread of Covid-19 pandemic had stipulated additional components beyond the scope given by the legal provisions. Therefore, the announcement was not valid and could not be used by the court to inflict punishment.

Furthermore, some courts believed that for a public assembly to violate the Emergency Decree, it must affect the national security under the “Emergency Situation” according to Section 4. Thus, the fact that the defendants invited people to join the assemblies and participated in the assemblies themselves were not sufficient grounds to constitute an offence.

Given the elaborated patterns, all ongoing car mob cases in various stages should not have been considered an offence in the first place. Public prosecutors should stop indicting them and withdraw those cases in the process to lessen the burden of both the accused as well as those in the justice system, including their time and budget spent on the cases that emerged only from people trying to exercise their civil rights and freedom.

Read more:

Nationwide Car Mob Cases Summarized: At Least 244 People Accused in 96 Cases

8 Years After the Coup: Politically Related Cases from the NCPO Era Remain Active.