Our interview series “First Sermon before taking the path towards democracy: Background stories before the political awakening of Ratsadon monks/novices” are divided into three parts. Each of them presents the stories of individual monks and novices with unique backgrounds and paths leading them to join the fight for equality.

Read Part 1 >> Luang Pee Phupha: On being a Phu Paan kid, reading a protest poem on stage, and establishing the “Carrot Gang”

The Childhood of “Samanera Folk”: Inspiration for Pursuing Buddhist Education

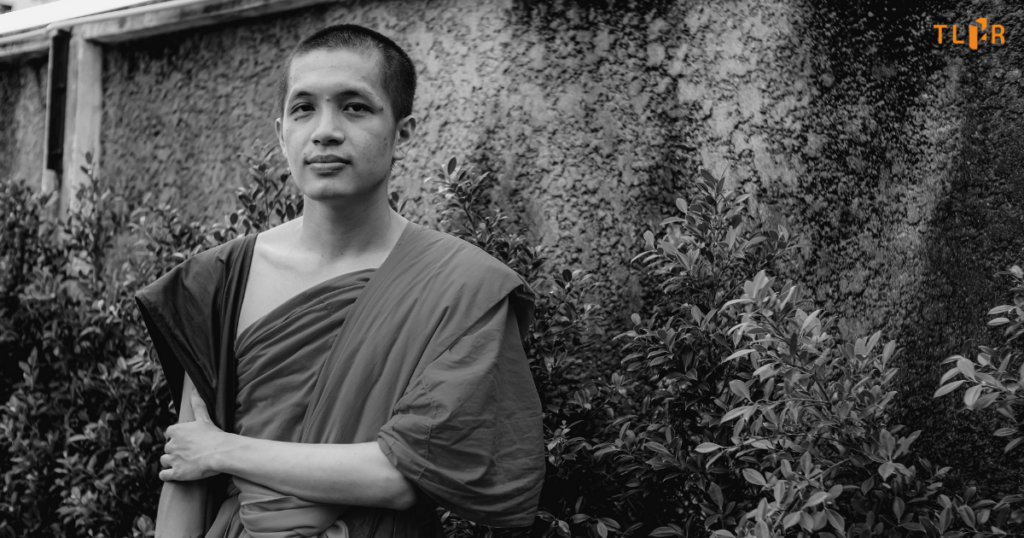

The early life of Saharat Sukkhamla or “Samanera [Buddhist novice]Folk,” a 21-year-old novice, is similar to the story of Luang Pee Phupha. Recently, Samanera Folk was informed of his “royal defamation” charge for allegedly violating Article 112 of the Criminal Code by delivering a speech in the “Goodbye, Dinosaurs” rally held by the “Bad Students” Group on 21 November 2020.

Samanera Folk is originally from Chiang Kam District of Phayao Province. Speaking about his early life before becoming a novice, he said, “When I was 7-8 years old, I had not been ordained yet. My grandfather was a school bus driver. During former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinnawatra’s administration, our family was in a good financial situation. We had sufficient savings for covering down payments on a bus that we used for our business. However, in 2006, the army staged a military coup. Simultaneously, my grandfather got sick and eventually passed away. Meanwhile, I had lost my father since I was three years old. All these incidents ended my family business because no one else could drive the bus. We also stopped investing in investment funds. Accordingly, our financial status gradually worsened.”

Samanera Folk told us that the uncertainty in his life made him struggle continuously with educational problems from a young age. “When I was in Grade 4-6, I really liked playing football. Chiang Rai United Club was very famous at that time, and they held regular recruitment events at the Chiang Rai Municipality School. If I got into that school, I could try out for the football club every year. I could become another Cristiano Ronaldo. I heard he also used to be just another poor kid in Portugal. However, when I got admitted into the school, I only got a partial scholarship enough for the tuition fee. My family still had to cover the accommodation and food costs, which they could not afford. My grandmother and mother said I had to choose: if I went to that school, my younger siblings would not have any education.”

Due to his family’s financial limitations, Samanera Folk’s siblings might not be able to receive education. As a result, he faced a dilemma between pursuing his childhood passion and giving his sister an educational opportunity.

“At first, I did not want to get ordained because I liked football very much. I wish I could pursue my dreams like children in Europe do. I truly believe that even those living in poverty could succeed in life. However, I had to make a decision that enabled my family to survive despite our limitations. Therefore, I entered a summer ordination program when I was 12 years old.”

Reflecting on his past, Samanera Folkrealized that, earlier in his life, he had some interests in religious affairs – not in Buddhism but instead in Christianity.

“Actually, there were some good moments in my childhood. I used to help my grandfather sell stuff near the mountain area when I was around 7-8 years old. There was a Christian church there, where churchgoers liked to sing, learn English, and play the piano. The church also regularly handed out chocolate and cookies. I think it was real chocolate, not an artificial one that we normally could find in local stores. I can recall my excitement when the Brother from that church told me that a benefactor from overseas would bring presents for the children during the Christmas period. I really wanted to own some toys from Europe.”

“When I was at the church, I did not have to think about anything. It was as if I forgot all my grievances completely,” Samanera Folk recounted his childhood memory about Christianity.

Nonetheless, when his grandmother found out that he went to the church and started to develop some interests in Christianity, she was afraid that he would convert his religion. Therefore, she took him to a Buddhist temple and asked a Luang Ta (Revered grandfather monk) to care for him. From then onwards, he neither had a chance to say goodbye to the Brother nor return to the church.

SOTUS and beatings in Buddhist temples: “The previous generation also went through this.”

“I got ordained as a novice when I was 12 years old like Luang Pee Phupha. However, I was not happy about it; I cried in my backyard for three days,” said Samanera Folk jokingly. However, he said he could not really joke about this at that time. After he got ordained and pursued Buddhism studies in a temple in his local area, he encountered what he called “SOTUS and beatings” there. [Translator’s note: SOTUS is an acronym for Seniority, Order, Tradition, Unity, Spirit. It is a value used for justifying violent hazing in many institutions in Thailand, including schools, universities, and religious organizations.]

Samanera Folk explained that the monk teachers did not cane the students as in other educational institutions. Instead, it was senior novices who caned juniors studying Buddhism in the same temple. Those who could not recite the mantras would be beaten with a cane until they could memorize the verses.

“You would be caned more and more if you continue to fail to recite Buddhist mantras – from three to six to nine to twelve times. My calves still have some scars from those times. Not only could I not remember the verses, but also I did not want to be there at all. I wanted to run away as far as I could. I did not want to remember those verses because I did not know what I would be facing in the next three days. As I often ran away from practices, senior novices would bully me by hiding my towels and covering me with a saffron robe and beating me.”

From the ages of 13 to 16, Samanera Folk, alongside 50 other novices from various backgrounds, had to experience the SOTUS system in the temple. Even though he tried to inform senior monks that he was bullied, those monks would tell him that he should not be so weak, and that the previous generation of novices also went through the same thing.

“When I was in Grade 10, I was old enough to mentor younger novices. I moved to a monk’s hut in the forest because few people wanted to go there. My approach of teaching the novices features using YouTube videos to help them learn the mantras so that the novices could feel like they are listening to music. If they could not remember the verses, I would give time to practice and memorize them.” Samanera Folk, therefore, had the opportunity to make changes and use a different approach to treat other novices to ensure they do not have to go through what he experienced. Still, he heard stories from other monks and novices in the temple, which deeply disturbed him.

“One of my novice friends was raped by his monk teacher when he was living in another temple. Then he moved to my host temple. I feel that sexual violence in temples in the Northern region is so rampant that it is almost perceived as normal. This abbot who abused my friend also had previous records of committing sexual violence, but he could remain in the temple because other senior monks have helped protect him.”

Life-changing passion in history

Apart from learning about Buddhism and the Buddhist clergy, Samanera Folk also developed an interest in world history in his teenage years. Later, such an interest would help shape his political ideas.

“When I was in Grade 10, I began to have internet access and learned about interviews of academics about world wars from National Geographic’s documentaries. These shows sparked my interest in politics. For instance, I learned about Japan’s involvement in the wars and started to wonder what Thailand’s role was.”

This curiosity stemming from the war documentaries coincided with his discovery of a video recording of an academic seminar about Meiji emperors convened by Professor Likhit Dhiravegin. Subsequently, the discovery snowballed, and he discovered many other online contents that inspired his learning.

“After watching Professor Likhit’s video, I found out about Prachatai and shows run by ‘Khaek Kampaka’ and ‘Pokpong Chanan.’ I felt like I was hungrily chasing for the knowledge that I had been missing. Meanwhile, I began to grow apart from my schoolmates as if we were speaking different languages. Most students at my school for novices only wanted to play the online game called “ROV.” Almost none of them took the GAT-PAT national university admission examinations. They all thought there was no need to take the test because it was useless to earn a university degree. Only one of my friends and I took the tests so that we could continue our studies in Bangkok.”

Samanera Folk recounted that, throughout Grade 10-12, he had received a scholarship from Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, which enabled him to take training courses at Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University in Ayutthaya Province many times. His passion for social sciences and history increased, thereby changing his daily mannerisms. This life-changing juncture created distance between him and his friends due to diverging interests in life and caused cumulative stress for him. At the time, he felt like he could not talk to anyone but his teachers and very few of his friends.

Despite the stress, Samanera Folk grew close to another monk who took him to practice the dharma. This monk liked to share various meditation approaches with him, which Samanera Folk found strange, such as practicing meditation skills through games, going on a 7-to-15-day forest retreat, or looking at asupha (corpses) including at dead bodies that are not completely burned.

“During that time, I began to question why I was born,” said Samanera Folk.

This monk also brought him to Bangkok and introduced him to Thammasat University and its students. Samanera Folk said that he discovered many interesting things from listening to Thammasat students’ conversations. He also felt thrilled to explore the Pridi Panomyong Library at the University’s Tha Prachan Campus due to the number of students using the library and numerous intriguing books there. His fellow monk also took him to a bookstore, where he bought some books to read.

“The first book I bought was the Thai version of Marx: A Very Short Introduction translated by Professor Kasian Tejapira. I did not really understand the book, but I was excited about it. I was eager to find out who Karl Marx is.” He jokingly said that owing to his newfound interests in Marx, he looked up videos on YouTube to gain more knowledge. He, thus, found the seminar on Marxism, “Karl Marx: Myth or Science?” led by Pichit Likitkijsomboon on the occasion of the 200th Anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth.

After finished taking the GAT-PAT university admission examinations, Samanera Folk was accepted into Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University. After four months, he took the course “Introduction to Philosophy” and enjoyed it because it served as a space for open discussion. He also liked another course called “Thammapak” where he learned about the categorization of different groups of dharma. He found the knowledge obtained from this class serves as a helpful foundation for further research on Buddhist principles.

Despite enjoying some courses at Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University, Samanera Folk also wanted to try applying for Mahidol University’s College of Religious Studies because the course curriculum is interesting. Eventually, he was admitted to a bachelor’s degree program there. Still, he found it hard to compete academically with other students, especially in the English language. This issue made his university grades significantly drop from his secondary school grades.

Internet and new environments that give answers to curiosity

Samanera Folk said, “Actually, I have been following “Professor Somsak Jeamteerasakul” since I was in Grade 11. My Phra Ajarn (monk teacher) liked to listen to his lectures, so I also listened with him. However, back then, I was mad because I got a scholarship from Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn and thought she was very kind to me. I wondered why this professor had to keep talking about the monarchy and why he did not attack politicians in the same way as he did the royal family. Still, I was struck by a video recording of one of his lectures where he said that he would criticize the politicians should a similar mechanism be put in place to prohibit criticisms against them in the same way as the current laws enforced to ban royal defamation.”

For Samanera Folk, it is difficult to determine who exactly sparked his interests in politics. However, he mentioned that, before Thailand held its General Election in 2019, he listened to a video recording of an academic seminar of Professor Thamrongsak Petchlert-anan from Thammasat University. The forum features a discussion about the 1932 Siamese Revolution, the student uprisings on 14 October 1973, and the massacre on 6 October 1976. The historical knowledge from this seminar helped him understand the student movements and the distortion of the students’ demands in the mainstream historical narrative.

He began developing interests in the history of Thai politics and watched many relevant videos. In 2019, he physically participated in the seminar “13 Years after the 2006 Coup d’Etat: Overcoming or Repeating the Cycle of Tyranny – Are We Done with Coups and Authoritarian Leaders?” The panelists included Pasuk Phongpaichit, Thamrongsak Petchlert-anan, and Pitch Pongsawat. He also met a group of Chulalongkorn University students at the event and exchanged a list of interesting books with them.

“Later, the Future Forward Party was dissolved. I thought I could not take it anymore and had to take some action. My friends from Mahidol University staged a rally and created protest signs inside the campus. At first, my friends wanted me to go up on stage to deliver a speech, but I chose to do behind-the-scenes work instead.” Working with my university friends allowed me to exchange political ideas and expand my network with activists in various groups. This opportunity enabled Samanera Folk to find his path to embarking on social activism.

“Many meetings for students from many universities were held to allow us to exchange ideas about activism. Taking part in such meetings makes me realize that there is no turning back for me.” Samanera had continuously read news reports, articles, and weekly political analyses to improve his knowledge about political history. Then he began reading books from the Same Sky, a publishing house specialized in Thai politics, to learn even more.

“In my temple, the abbot typically asks us to read books and provide him a summary one or two days before each public sermon to allow monks and novices to practice delivering sermons. I chose to read and summarize Same Sky books from the “Siam Criticism” edition. The abbot is a very open-minded person; he permits us to pick any books.” As Samanera Folk needed to summarize the books for the abbot, he had to finish them as soon as possible. These books helped him understand more about the history of political struggles in the Northern region where he was born as well.

Samanera Folk further revealed his perspectives on the position of monkhood in society. “Being a monk allows me to see that poor and rich people continue to give alms despite the current COVID-19 situation, even though we should be giving to those who are starving instead. The current solutions are not addressing the issues at their roots and could not solve anything effectively. We need to join a movement to drive structural changes; such a move will help everyone access housing and adequate food, enjoy a good economy, and pursue their dreams.”

“Bad Karma” of monks and novices involved in political movements

Samanera Folk is currently facing three charges for his political involvement, including one charge under the “royal defamation” law, which contains a severe penalty. Nonetheless, these lawsuits are not the only issue he is encountering. After becoming actively involved in political movements or expressing political opinions, he has been subject to surveillance and harassment by the authorities. He is also prone to the risk of getting forced to leave monkhood.

“What severely impacted me was the attempt of the Office of National Buddhism and the police to track me down last year (2020). It seemed that they wanted to force me to leave monkhood. I was not subject to monitoring only in one place. Rather, they followed me everywhere, including my dormitory, host temple, and even my friend’s house. It made me feel like nowhere was safe for me.”

“Fear and paranoia had taken over me, making me wonder how much longer I could live. I was afraid that I would be subject to enforced disappearance. So many thoughts popped up on my mind.” Samanera Folk told TLHR about his fear as he witnessed the state’s actions against monks and novices involved in protests. He explained that he managed to get through that phase thanks to his friends.”

“My friends help convince me that the evil is always present in the ordinary. Their help relieved my fear, but I do not necessarily think that way of thinking is good. Violence is violence; we should never normalize it,” Samanera Folk reflected on his past.

“This year (2021), officers from the Special Branch Police visited my Phra Ajarn to obtain some information. I felt like the harassment was endless. The authorities also tried to force me to leave monkhood on 7 July 2021 when I went to the police station to acknowledge my charge under Article 112 of the Criminal Code for delivering a speech during a protest in November 2020.”

Samanera Folk recounted this story of harassment on his personal Facebook account. After acknowledging his charge at the Pathumwan Police Station, the police officers asked for a meeting with him. Three representatives from the Office of National Buddhism also joined the meeting. They claimed that Samanera Folk failed to return to his host temple after the abbot summoned him to give him a warning on 3 November 2020. Therefore, his inaction constituted a violation of dharma disciplines that shall result in Lingkanasana (Expulsion from the temple). Furthermore, according to the Sangha Supreme Council of Thailand’s resolution, a novice must be expelled from the monkhood if he does not have a host temple.

However, it was proven that Samanera Folk’s host temple did not issue the summons for him. Therefore, the authorities could not expel him from the monkhood on that day due to the errors in their documentation. Samanera Folk raised many questions regarding this incident:

“I wonder how they could even try to accuse me of defaming and threatening harm for the Sangharaja (Supreme Patriarch of Thailand). Even the Buddha never really imposes any dharma doctrines to regulate the defamation and threats against him. Why are the authorities using this law promulgated 200 years ago and ignoring the dharma doctrines which have existed for up to 2,500 years? That would be an insult to the dharma doctrines. How could they only adhere to the secular laws without using the examination procedure in accordance with the Sammukkha-Vinaya (Translator’s note: Rules for adjudication for violations of dharma doctrines under the Tripitaka)principles?” Samanera Folk said that if the authorities wanted to expel him from the monkhood, at least they should have processed the documents correctly.

If only “monks and novices” are recognized as citizens

“Being both a monk and an activist causes many challenges for me. I am always on top of the police’s list for prosecution for every rally I have attended because the color of my saffron robe is very noticeable. It feels like the authorities want to suppress all of us. My affiliation with the host temple is also a significant constraint on my political activities. Typically, in Sangha affairs, our actions should depend on a decision jointly made by two or more monks. However, in the current state of affairs, the abbot solely holds a decision-making power to expel or accept anyone into the temple. The abbot could even hire all his relatives to work at the temple. Meanwhile, if we upset the abbot, we might be expelled from the temple. In sum, we are treated so poorly as if we were animals.”

When Samanera Folk was asked if he ever felt worried or hopeless during his involvement in political activism, he immediately responded, “I am from the lower class, and I am betting so much on this fight. I will feel hopeless when others think that this battle is not serious.

However, I never regret anything and want to continue my activism, even though I am concerned about my family’s safety. The abbot at my host temple is very kind and offers to pay half of the tuition fees for any monks and novices who want to pursue their studies. Consequently, I have to work at the temple during the weekends to cover the other half. From the second semester of my freshman year onwards, I would no longer have the scholarship to cover for the fee.”

The public may view monks as a privileged class with a comfortable lifestyle due to the respect they receive from society in general. However, Samanera Folk believes that monks’ privilege in this Buddhist society comes at the cost of tremendous responsibilities and expectations. Meanwhile, he only wants simple things in life.

“Monks have a lot of cultural capital, but it is not easy to make people accept us. What we want is not the right to use public transportation for free. Rather, we prefer to be equal to others, enjoying the opportunity to earn as much income and having the right to participate in elections.”

Better education for transforming the Sangha clergy’s future

Samanera Folk views that, in the future, the Sangha should be governed under the dharma doctrines. Furthermore, the legal status of monks could be changed.

“To me, we should repeal the Sangha Act B.E. 2505 (1962). Furthermore, we should give monks citizenship status and turn temples into juristic persons or private companies. We could require temples to pay taxes and record income and expense accounts. Importantly, we should allow everyone to choose their religion to ensure diversity in our democratic society.”

He further added on the issue of Sangha reforms, “Monks and novices might be engaging in activism underground. Many monks are pro-reform, but they are waiting to see how the political situation unfolds. Once the power dynamics shift, the Sangha will likely change too. No matter what, I believe that the Sangha will be transformed by capitalism. Merit-making, for instance, has already been commodified. It now depends on how religious institutions adjust to such a change.”

“If temples could be registered as a juristic person, I have an idea of transforming them into a for-profit complex where we could take care of and organize activities for the elderly and host public sermons and discussions where we can invite academics to join as speakers. This would help the elderly feel less lonely. Also, monks will no longer have to hold fundraising ceremonies to gain monetary and other necessary support from temple goers. Instead, they could live off the income generated from this management model.”

Furthermore, Samanera Folk thinks that it is essential to give more importance to improving educational quality for monks and novices to reform the Sangha.

“I would like to be treated as an ordinary citizen. It is crucial to provide monks with the ability to access good education to realize their potential. Buddhist schools where monks attend should be developed so that their quality matches that of regular schools. In my former school, contract teachers only earn 6,000 THB (179 USD) per month and are often overwhelmed by paperwork which hinders their full ability to dedicate their time to teaching. As a result, students have an opportunity to learn only a bit of subject that should be fundamental courses.

“If possible, monks and novices should be able to maintain their practices while attending schools with other normal students. Then, after they finish regular school, they could return to the temple to take additional classes on Buddhism. If Buddhist schools have the capacity to operate in the same way as many renowned Catholic schools, they should do it.”

“One phrase from Marx that I find impressive and keep replaying in my head is, ‘Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.’ I think that it is important to begin making changes. We should not only attempt to explain social phenomena but rather drive changes in the society for the better.”