As 2016 is drawing to a close, the exercise of power purported to uphold the “law” and “justice process” of the NCPO continues to become more intensified amidst severe restrictions of freedom of expression of the people in Thailand. The military are still vested with power to report cases, carry out arrests, and try political dissents just like over the past two years since the 2014 coup.

Meanwhile, the “court” was a part of the equation. Not just the Military Courts, with bestowed power from the NCPO to try civilian cases, the Court of Justice together with the Administrative Court and the Constitutional Court have engaged in the practice by issuing orders to legitimize the NCPO as the lawful sovereign. In a democracy, the judiciary places an indispensable institution to implement check-and-balance and judicial oversight under the separation of powers principles. With power to justify the NCPO and its policies, including hundreds of announcements, orders, and practices, the court is a key actor in post-coup political context in Thailand.

This report is an attempt to explore eleven representative contributions of the Courts to military rule in Thailand, collecting verdicts, orders, hearing processes and interesting conducts in 2016. It also encourages the audience to consider whether the judiciary as a stakeholder in Thai politics, with great effects on the cause and proliferation of national conflicts for the past few years, or an independent actor under the principles of impartiality and neutrality.

1) Military Courts continue to try civilian cases

On 12 September 2016, Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha invoked Section 44 of the Interim Constitution to issue the Order of the Head of the NCPO No. 55/2016 to withdraw the power of the Military Courts to try new cases against civilians in offences concerning the monarchy, national security and other offences relating to the Announcements or Orders of the NCPO, effective from the day the Order was made. But in more than two years since a few days after the coup, nearly one thousand civilians have to be tried or are being tried in Military Court as a result of the Orders of the coup makers.

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) has learned that according to the Judge Advocate General’s Department (JAG) in charge of the Military Courts, from 22 May 2014 to 31 May 2016, 1,811 civilians were indicted in Military Court, in over 1,546 cases, of which 517 have not been finished. Therefore, even though the Order of the Head of the NCPO has been made, defendants in over 500 cases will continue to have their destinies decided by the Military Courts.

In addition, the offences that took place from 25 May 2014 to 11 September 2016 have been indicted retrospectively. For example, in the case of Small Bundit Aneeya who publicly commented on the draft Constitution, although the incident took place in 2015, the arrest and prosecution were made just in November; nevertheless, he has been indicted before a Military Court. Similarly, the case of Ms Sirikan Charoensiri, a human rights lawyer, charged with sedition per the Penal Code’s Article 116 together with 14 activists of the New Democracy Movement (NDM) relating to an incident that took place in June 2015, was only summoned to hear the charge in September 2016. Yet her case, if it proceeds, will go before the Military Court, since the offence was committed during the time that Military Courts were authorized to try such cases.

Therefore, even if the power of the Military Courts to try cases against civilians seems to have ceased, there are many outstanding cases that will ensure that the Military Courts will have more chances to make their contribution, including ongoing cases, and other cases that have yet to be indicted. But at least, after over two years, the Military Courts have managed to complete witness examinations and has delivered verdicts in two political cases. What a success!

2) Military Courts’ unusual opening hours and the absence of stationed judges

The working hours of a Court in Thailand are 8.30 a.m. to 4.30 p.m. But the Military Courts have opened and closed as they have deemed fit, as a result of the arbitrary use of power by the NCPO, though they have failed to protect people’s rights and freedoms. For example, in the case of 15 suspects who were alleged to have founded the Revolutionary Alliance for Democracy Party last year, after the taking of evidence from the alleged offenders was completed on Friday, 19 August 2016 at 2.30 p.m., they were brought to the Bangkok Military Court for a remand hearing. During the hearing, their attorneys asked to place bail bonds, but were told by the court clerk that it was nearly the end of working hours and the bail applications should be made on Monday instead. That meant all the alleged offenders had to be brought back and held in custody at the prison. But on the very same day, around 8.30 p.m., the Court of the 23rd Military Circle in Khon Kaen was open and conducting an arraignment hearing ion the case against Mr Jatupat Boonpattaraksa, aka Pai “Dao Din,” as a result of his anti-coup activities at the Khon Kaen Democracy Monument on 22 May 2015, and the judge advocate carried on with indicting him in the Military Court. The Court had Jatupat remanded in custody and he was later brought to the Central Prison of Khon Kaen the same day.

Such incidents also happened in 2015. The 14 students and activists of the New Democracy Movement (NDM) were brought to the Bangkok Military Court for a remand hearing at 10 p.m. and the whole remand hearing process was not completed until 00.30 a.m. of the following day. It seems a Military Court can open and close anytime if the authorities really want to press ahead using the law against their political accused.

In addition, TLHR has found that judges in the Military Courts of different provinces rotate, and as a result, on certain days some Military Courts have no judges and no one to review the requests tendered by concerned people at the court. For example, relatives of a glasses salesperson who was alleged to have violated Article 112 went to apply for his bail at the Court of the 37th Military Circle in Chiang Rai on 25 October 2016, but there was no judge at the court then. The officer on duty told them that the judge there was on rotation and had gone to hear cases in another Military Court. As a result, the bail application had to be postponed.

3) Military Courts and the prolonged justice process

One of the unique characteristics of trial in Military Court that has become more pronounced this year is the prolonged hearing process, particularly in cases where the defendants are remanded in custody or plead not guilty. The Military Courts only schedule hearings and issue a witness summons one at a time, in contrast with a fixed set-up used in civilian courts. A hearing is arranged every two or three months. In some cases, the courts only hear cases in the morning. As a result, the examination of one witness may take several hearings. Many cases have seen rescheduling since the plaintiff’s witnesses, oftentimes government officials summoned by court-issued witness warnings, did not show up. Until Now, based on TLHR’s documentation, the Military Court has managed to complete witness examination and delivered its decision in just two political cases in which the defendants pleaded not guilty.

This year, the Military Court has delivered a verdict in just the case against Sirapop, alleged to have defied an order from the NCPO summons. He was apprehended on 25 June 2014, and later indicted on 15 August 2014. The Military Court fixed 11 November 2014 as the first hearing for prosecution witnesses. But the examination of the first witness did not really commence even until after six more months as the witness was busy with something and could not go to the Court. The examination of the witness was only completed on 4 November 2015, so it took one year in total to examine just one witness. Finally, the Court has just delivered the verdict on 25 November 2016. The trial basically lasted over two years. Worse, the defendant has been remanded in custody during the trial already, even though the maximum punishment for his charge is just two years’ imprisonment.

Another intriguing delay happened with the case against Anchan, a defendant alleged to have violated Article 112, lèse-majesté offence. The arrest was made on 30 January 2015 and the case was indicted on 23 April 2015. For over one year and eight months, seven witnesses gave evidence, during which time there were four instances of rescheduling as the prosecution witnesses were simply absent from the Court three times. Only two witnesses managed to give evidence during that time. But all along, the defendant was held in custody. Similarly, in the ‘Khon Kaen Model’ case in which several alleged offenders were arrested just after the coup, the first witness examination just took place on 28 October 2016, over two years after the indictment. In this case, although the defendant was not held in custody during trial, the plaintiff has also proposed 90 witnesses and given that around 10-12 witnesses can be examined per year, at this rate it would probably take 7-9 years to complete the examination of all witnesses.

4) Military Courts practitioners’ statement in the UPR forum

Amidst the attention of the international community toward the use of the Military Courts to try cases against civilians in the past year, given that there was the Universal Periodical Review or UPR held in Geneva to review the situation in Thailand, the Thai delegation included officers directly involved with the Military Courts, namely Lt Col Saenee Promwiwat, Chief Legal Officer of the JAG, Ministry of Defence, who, made a statement at the meeting.

Lt Col Saenee explained to the meeting on 11 May 2016 that the Military Courts had been used to try only civilian cases of certain offences of grave crimes, and that the defendants indicted with the Military Courts are entitled to have the same rights as those tried by civilian courts. He maintained that the Military Courts adhere to the practices per the Criminal Procedure Code, guaranteeing the right to fair trial and ensuring that the defendants are entitled to rights according to international standards. The judges of the Military Courts, he claimed, ought to be knowledgeable and well versed in criminal law, just like judges in civilian courts.

Our observation contradicts Lt Col Saenee’s statement to the international community. A number of cases against civilians tried in Military Court concerned the right to freedom of expression. They are not ‘grave crimes’ at all, but cases such as people eating certain foods in McDonalds as an anti-coup gesture, cases of people defying the NCPO summonses, cases relating to activities to highlight the importance of elections, cases relating to an activist’s walk from home to Military Court, cases concerning a train ride to highlight corruption relating to the Rajabhakti Park project, cases relating to the mocking of the head of the coup makers, cases against academics conducting a press conference to declare that universities are not military camps, cases as a result of posing for a photo with a red bowl, cases relating to the launch of Referendum Watch Centers, cases relating to a public discussion on the Constitution, or even cases reported against human rights defenders who were simply observing public activities in defense of human rights. All of these accused have been indicted with the Military Courts.

Civilians tried in the Military Courts have also been deprived of many rights, contrary to the claim made by Lt Col Saenee that those civilians accused have been accorded with the rights same as in civilian courts. For example, those indicted during the 10-month imposition of Martial Law have no rights to appeal against sentences, if convicted, to a higher court. The Military Courts also have no examination procedure, no public defender system, and lawyers are even prohibited from copying docket reports in certain cases. There are differences in terms of bail bonds and how the alleged offenders or defendants are brought to the prison while the bail application is being reviewed. As a result, many female alleged offenders have had their rights infringed upon, as they had to undergo strict body searches before entering the prison. Also, judges in Military Courts are required only to be commissioned officers appointed by superior officers in various agencies, and are not required to have a law degree at all.

Also, as to the claim that the Military Court is no different from a civilian court, why did the Head of the NCPO Order No. 55/2559, which reverted to the hearing of cases against civilians back in civilian court, cite as a reason that “it intends to relax measures to allow parties to exercise their rights, to perform their duties and to have their protection per mechanisms under the new Constitution which shall be promulgated very soon, as well as to uphold the rule of law and human rights principles”? The statement seems to indicate that the previous use of Military Court to try civilians has not led to the upholding of the rule of law and human rights principles at all.

5) The Courts failed to protect freedom of expression during the run-up to the Constitutional Referendum

It was not surprising to see the Constitutional Court determined that Section 61, paragraph 2 of the Constitutional Referendum Act was not in breach of or incompatible with the 2014 Interim Constitution’s Section 4, after the Ombudsman received a complaint that it infringed the rights and liberties of Thai poeple. Nevertheless, the reason given by the Court for its decision was extremely disappointing to pro-democracy groups. The Constitutional Court justified its ruling on the grounds that “a state organ [is] responsible for managing voting during the Constitutional Referendum…” given the political instabilities the country was facing. The legislation is in contrast with international standards that require “the state to allow people who have different opinions to express themselves and to disseminate information freely and equally.”

People were again disappointed by the order of the Supreme Administrative Court which refused to hear the case filed by civil society groups, demanding the rescinding of the ECT Notification concerning the procedure and methods of public expression during the Constitutional Referendum, since it tended to disproportionately restrict the right to freedom of expression and not be in compliance with the law. The Administrative Court dismissed the case on a technicality, by claiming the complainants were not the injured parties and therefore had no legal standing to file the case, and that the notification was simply an advisory document which carries no criminal punishment for its violation.

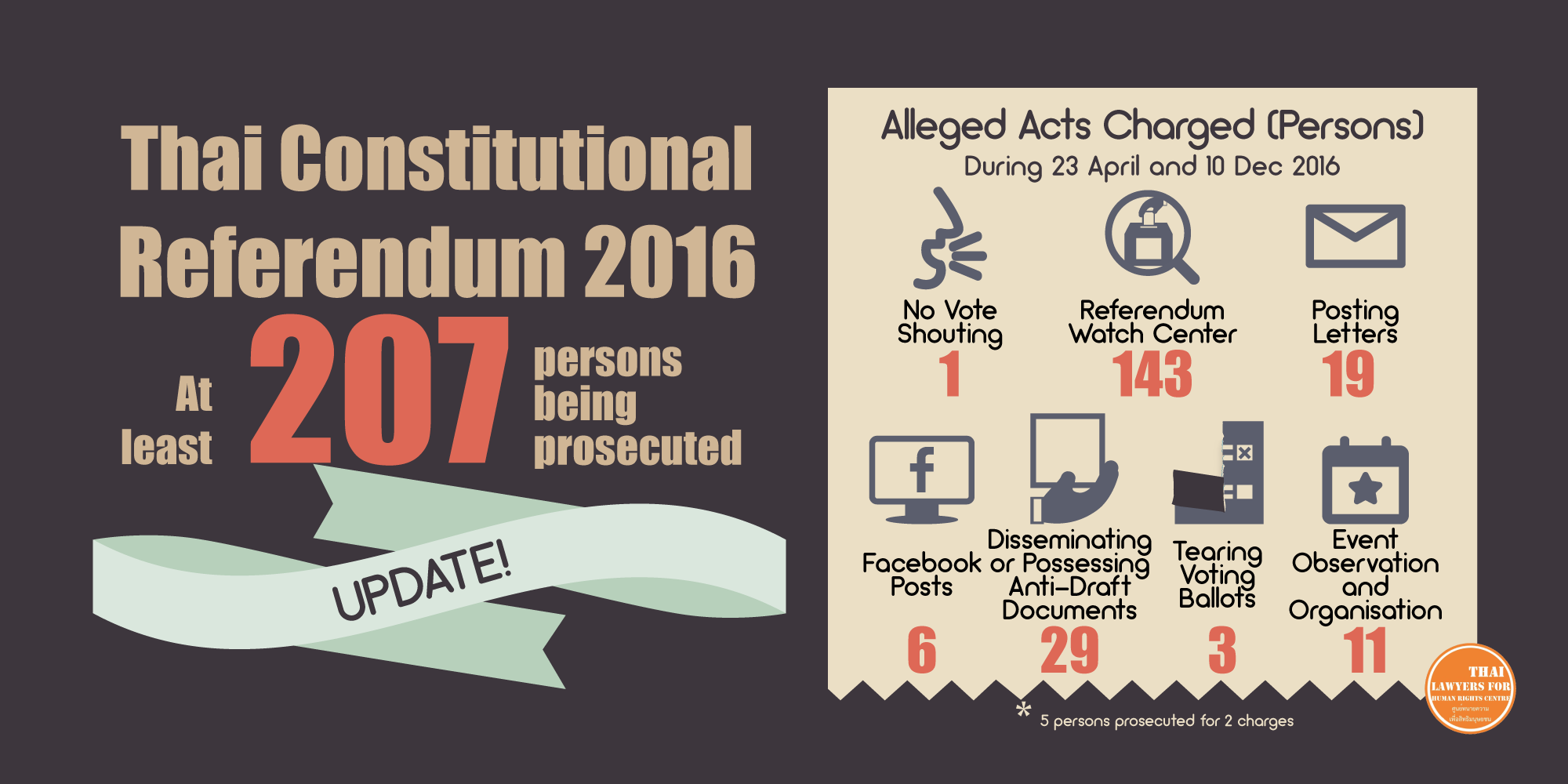

Failure to protect freedom of expression during the Constitutional Referendum has resulted in the prosecution of at least 207 persons who had been engaged in campaigning prior to the referendum. At least 47 of them are accused of violating Section 61, paragraph 2 of the Constitutional Referendum Act. Many activists had been warned against holding public campaigns and faced harassment and intervention. The general public was intimidated and too scared to express themselves. For example, they did not even dare to wear ‘Vote No’ shirts. Note that a reporter and human rights activists are among those facing prosecution.

People prosecuted for violating Section 61, paragraph 2 of the Constitutional Referendum Act might wonder why it is the case. Both civilian courts and the Military Courts have allowed them to be remanded in custody or have asked for very high bail bonds (60,000-150,000 baht), putting a heavy burden on people who simply exercised their rights to express themselves on issues so vital to their lives, such as the Constitution.

Since the Draft Constitution was endorsed in the Constitutional Referendum, at least eight cases have been indicted without grounds of it being of the public interest.

Even though no verdict has yet to be issued and the defendants are standing firm to defend themselves, the Court has already showed some skewed attitudes. For example, in a case concerning the alleged dissemination of ‘Vote No’ stickers, during the reconciliation meeting, the Provincial Court of Ratchaburi made an attempt to have the defendants plea bargain. After the defendants refused to do so, the Court put in the docket report that the Court has read and explained to the five defendants about their rights and duties according to the law and the legal procedure in an effort to educate them, and has made an attempt to instill them with the awareness and sense of responsibility for the offences committed, but the defendants have insisted that they had done nothing wrong as alleged and want to fight the charges.

How could the public have any hope that such a justice process would eventually lead to more protection of rights and freedoms?

6) The Courts of Justice legitimizes the junta’s orders and the detention in military barracks

Throughout 2016, the NCPO continued to detain individuals in military camps by invoking the Head of the NCPO Orders No. 3/2015 and 13/2016 issued by Section 44 of the Interim Constitution. Yet, the Courts of Justice have even lent legitimacy to such exercise of power by the coup makers.

The case in point was the combined military and police raid and detention of the eight administrators of the “We Love Gen Prayuth” Facebook page in April 2016. The arrest of the eight was made while the officers had failed to produce warrants and inform the suspects of the reasons for the arrest. Their families had not even been informed of where they were being taken, until the NCPO spokesperson, Col Winthai Suvaree, stated that they were taken to the 11th Military Circle. The relatives, however, were denied visitation rights once they asked to see the eight at the barrack. Such practices by the officers could be tantamount to unlawful custody.

Families of four of the eight and their attorneys filed cases with the Criminal Courts invoking Section 90 of the Penal Code to have a habeas corpus-style hearing and to have those individuals released from military custody. The Court refused to conduct a hearing immediately. The following day, the Court ruled that this custody was lawful under the invocation of the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2015 and had not lasted more than seven days.

In another continuing case since 2015, Mr Thanet Anantawong, a sedition suspect, allegedly posted corruption scandals of the Rajabhakti Park. When Thanet was seized, his friend Mr Sirawith requested the Court to release Thanet, citing arbitrary detention. However, the court acquitted the request twice without conducting any hearing. Later, the Appeal Court ordered another review on a habeas corpus motion in a lower court.

In the first dismissal, the Court reasoned that it was not a prima facie matter, since Sirawith based his application only on the information about the custody from Mr. Piyarat Chongthep, his friend. In the second dismissal, the Court claimed that the custody was already lawful since the arrest warrant had been issued by the Military Court, and the case fell under jurisdiction of the Military Court per the NCPO Announcement No. 37/2014 and the Head of the NCPO Order No. 3/2015. In ruling so, the Court of Justice seems to have legitimized the exercise of power by the NCPO. Even though the Appeal Court asked the lower court to retry the case on 20 June 2016, the Court still ruled to dismiss and dispose of the application, stating that Thanet had already been released from custody.

That the Court of Justice has even legitimized the power to hold a person in custody, invoking Section 44, has made it very challenging for the relatives and attorneys of detainees to perform their duties to hold accountable the authorities who have deprived people of their liberty. As a result, persons held in custody are virtually excommunicated from the outside world (save for when the military allow them to make contact). This has made detainees more vulnerable to human rights violations, and simply encourages more similar kinds of custodial practices in the future.

7) Appeal Court justifies the NCPO’s legitimacy in the case against Sombat Boonngamanong

Apart from legitimizing the power of the military to hold a person in custody, in the past year, the Court of Justice has even recognized the power of the coup makers in rulings made on several cases. One of the most important cases was in a ruling made against Mr Sombat Boonngamanong, aka Bor Kor Lai Jud. The Municipal Court of Dusit read the verdict made by the Appeal Court in the case relating to his defiance of the summonses issued by the NCPO. The Appeal Court ruled on 30 June 2016 to overturn the verdict made by the lower court that had ruled that refusing to report oneself as summonsed by the military was not an unlawful act since the law concerning these summonses would not have retrospective effect. The Appeal Court instead held that the defendant was guilty of violating NCPO Announcements No. 25/2014 and 29/2014 and sentenced him to imprisonment of two months and a fine of 3,000 baht (approx. 85 USD) with the jail sentence suspended for one year.

According to the Appeal Court, the plaintiff had the legal standing to bring the case, even though the defendant argued that the NCPO had seized the ruling power unlawfully. “The fact appears that the seizure of power by the National Council for Peace and Order had been made successfully, it thus has to be regarded as the sovereign power,” the court held. Whereas the defendant claimed the completion of the coup has to be endorsed by royal command to recognize the legal status of the coup makers by having it published and disseminated in the government gazette, the Appeal Court has found that such interpretation “shall elicit a bizarre result and cause a problem to the control and maintenance of public order in the country. It also appears improper to engage the monarchy in the matter of reviewing the completion of the coup, when the institution is above politics. Instead, the circumstantial context indicates the success of the coup.”

As to the argument concerning the use of ex post facto law against the defendant, the Appeal Court found that “All the laws issued by the National Council for Peace and Order have become effective by themselves, but their lawfulness and enforceability shall be confirmed once more by the provisions of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand (Interim), B.E. 2557 (2014). Therefore, in this case, the law was not used ex post facto as claimed by the defendant.” The verdict in this case is one among those made in the past year to legitimize the power of the coup makers despite no legal basis to do so, along with a provision in Article 113 of the Penal Code to hold the person overthrowing the Constitution accountable for sedition.

8) The Administrative Court accepts to review a motion to repeal the MoJ’s on the temporary remand facility inside military barrack

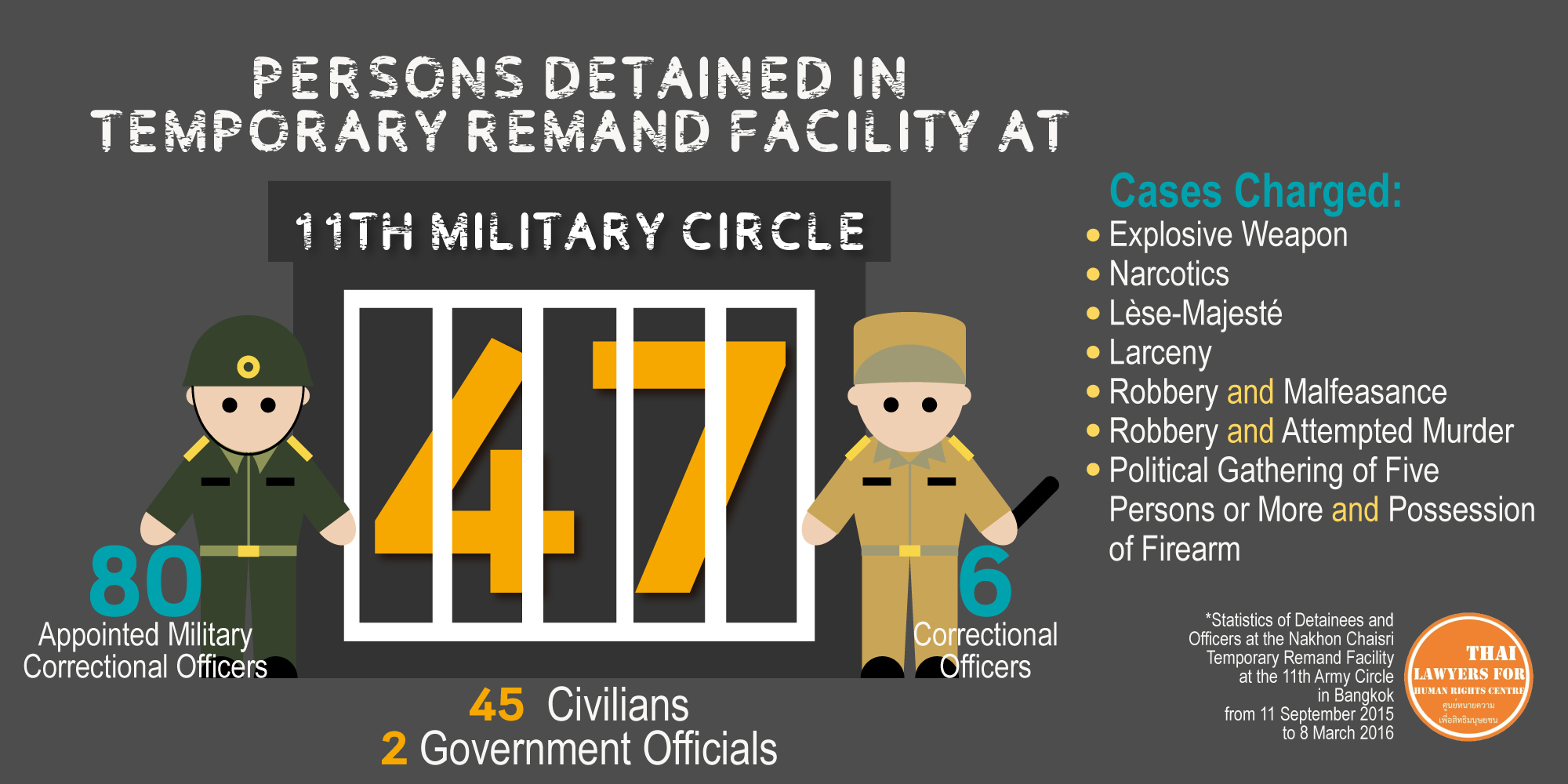

The establishment of a temporary remand facility inside a military camp continues to raise the prospect of human rights violations committed under the military regime. In late 2015, TLHR filed a case against the Minister of Justice to have the order of MoJ No. 314/2015 on the designation of territory of Nakhon Chaisri facility rescinded, claiming that the order’s content was too vague for the public to understand, and, as a result, in breach of the Administrative Act. It was also alleged that the facility was established for political reasons, thus, was an order made not in good faith, not compatible with the principle of equality according to the Constitution, and was a disproportionate exercise of discretionary power. Therefore, TLHR hoped that the Administrative Court would get involved to keep in check the exercise of power by the state.

Later it became known that apart from being located inside a military area, at least 47 persons were detained under constant monitoring of 80 special appointed correctional officers, whereas there were only six correctional officers from the Corrections Department. The place was also known as the last place in which Mr Suriyan Sucharitpolwong, aka “Mor Yong,” and Pol Maj Prakrom Warunprapa were held in custody prior to their questionable deaths.

The Administrative Court finally decided on 3 November 2016 to review the case. Next, the Court will tender plaints to the respondents to allow them to submit their evidence. The process to hold accountable the exercise of power by the state has just begun. Note that it took eleven mounts for the Court to accept the case. The proteacted process shows the redundancy of the mechanisms to check the duties performed by state officials, in a manner and to an extent that had never occurred until now.

9) When the Courts grant bail in lèse-majesté cases

Throughout 2016, both the Military Court and the Court of Justice have allowed bail for at least ten alleged offenders or defendants accused of insulting the monarchy, an offence per the Penal Code’s Article 112. It is well known how slim the chances are for alleged offenders or defendants in such cases to be temporarily released to prepare their defense outside the prison. The Courts tend to treat these cases as relating to national security, pertaining to a grave offence, and citing its heavy punishment and fear of flight as reasons to deny bail.

From the information collected by TLHR, those who have been granted bail can be divided into two groups. First are those deemed by the Courts as not having committed a grave crime, or those are likely to not be culpable, i.e., a post to mock the royal dog case , the ‘ja’ case of Ja New’s mother and sharing BBC Thai news. It is possible that the Courts might affix additional conditions to the temporary release, including prohibition against inciting the public or overseas travel ban, etc.

Another group, not quite so well known, consists of defendants who suffer mental illnesses, such as Sao, who had allegedly written a complaint and submitted it to the Supreme Court of Justice’s Criminal Division for Persons Holding Political Positions to demand money from a former Prime Minister. After the doctor had confirmed that Sao had been suffering from mental illness for a long time, the Court decided to dispose of the case and allowed Sao to receive treatment in order that he can fight the charge again. The Military Court also granted bail, requesting a surety of 400,000 baht in cash. Apart from Sao, there was also Ruecha who was indicted on an Article 112 case as a result of his Facebook post, which he had claimed had been posted by Mother Earth, as an ordinary person would not be able to draw such a graphic. After his attorney pleaded to the Court to have him referred to and receive treatment for his mental illness, once receiving the examination report from the doctor, the Military Court granted him bail.

Nevertheless, there has been a sharp increase of Article 112 prosecutions under the NCPO regime, along with a tendency of harsher sentences. The law has also been subject to broad interpretation, making clicking ‘like’ on a Facebook post an actionable offence per the Article. Thus, Article 112 has been criticized for being used as a political tool to purge dissents and to criminalize people with mental illness. The prosecutions against these people would eventually yield no benefit to the public and still, in several other cases, the alleged offenders or the defendants have often seen their requests for bail turned down by the Courts.

10) Courts conduct hearings and deliver verdict behind closed door

Problems remain this year as a result of secret trials in Article 112 cases. In the aftermath of the coup, several trials on lèse-majesté cases, indicted with the Military Court, have been conducted behind closed doors, similar to what has been done by civilian courts in such cases. Restrictions against trial observation and public exposure, and the prevention of attempts to copy docket reports or other testimonies, remain a big challenge and occur in both the Military Courts and civilian courts.

A case in point was the trial of Piya, a former stockbroker and defendant in Article 112 and Computer Crime Act cases. He was indicted on the same charge in two cases, whereas the Criminal Court has ordered that trials of both cases be conducted behind closed doors. The witness examination in his second case in late September was also conducted in secret, and no one else was allowed in the room during the hearing. The room was basically locked to prevent other people from getting in or out. The Court claimed the case had ramifications for national security and the monarchy. Also, during the reading of the verdict in October, the Court forced people not directly involved with the case to stay outside the courtroom. The Court also prohibited the attorney for the defendant from photocopying testimonies of the witnesses and the verdict, though the attorney was allowed to write it all down by hand.

An open trial and the right of parties to have access to the plaints and court documents is an important assurance to ensure fair trial per the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which Thailand is a ratifying member state. In its Article 14 (1), it is stipulated that everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing, and any judgement rendered in a criminal case or in a suit at law shall be made public except where the interest of juvenile persons otherwise requires or the proceedings concern matrimonial disputes or the guardianship of children. Even though Article 177 of the Thai Criminal Procedure Code provides the Court with power to conduct a closed trial, its Article 182 paragraph 2 succinctly states that the Court must read the verdict or the judgment publicly, without any exemptions. By locking the courtroom and reading the verdict in there, the Court basically breached international standards and domestic law.

11) Court revokes bail of lèse-majesté suspect

Toward the end of 2016, Mr Jatupat Boonpattaraksa, aka Pai ‘Dao Din,’ was charged under Article 112 of the Criminal Code and the Computer Crime Act for allegedly sharing a BBC Thai article, whose content narrates the biography of the new King of Thailand, and was released on 4 December 2016 on bail. However, on 22 December, the Khon Kaen Court accepted to review the police request to revoke the bail. After two hours of secret hearing, the Court ruled in favor of the police, citing that “the suspect did not delete the alleged public post on Facebook, had allegedly posted a satirical message mocking the state power with no fear of the law, and, as a result, damaged national security.”

Later on 27 December, the Appeal Court has endorsed the decision, seeing that “the suspect did not delete the alleged public post on Facebook, allegedly expressed symbolic comment mocking the state power on online platform with no fear of the law, and, as a result, damaged national security. The suspect is also likely to commit further similar acts. If released, the suspect might tamper with evidence or cause other types of damage.” The Court, therefore, acquitted the appeal for the lower court’s decision.

Such order, along with the controversial legal actions against freedom of expression on online platforms, pose a big question to law practitioners and the general public as to how such acts are deemed mocking the state power, and how “mocking the state power” could lead to the revocation of bail. The Court’s statement, in turns, appear contradictory, since the suspect not deleting the alleged Facebook post is, on the contrary, the act of not tampering with evidence.

Eleven “contributions” of the Courts are only parts of many more cases worth scrutinizing. They are emblematic examples of the enforcement and justification of the law to reflect the delivery of justice in the courts, including the check-and-balance and judicial oversight, especially in a non-democratic context of present Thailand.