One of the key milestones of the political movement since 2020 is the active participation of women and LGBTIQ+ groups, who have been taking up a leading role within the movement. The statistics of people politically accused since January this year show that at least 293 protest leaders or general citizens (including youths) facing lawsuits were female. On the other hand, at least 43 protest leaders or general citizens (including youths) belong to the LGBTIQ+ community. In terms of the number of the accused/defendants, almost one third were female.

In addition to harassment and accusation by the state due to their pro-democracy stance, female and LGBTIQ+ activists also experience gender-based biases and discrimination by police officers as opposed to male counterparts. Authorities often use a language that is bordering on sexual harassment, while the judicial procedures lack understanding about the rights over one’s body. All of these can contribute to long-term impacts on their mental health.

The Thai Lawyers for Human Rights presents you stories of gender-based harassment and biases through the eyes of political activists and lawyers who provide legal assistance for them. They will share their experience with state authorities and reveal violence hidden under the justice system that may not have been talked about elsewhere.

Nalinrat “Muay” (last name undisclosed), activist for gender equality and safe space in school.

Muay told us three instances of sexual harassment by state authorities, all of which occurred at the end of 2020 when the Ratsadon protests were at their peak.

Muay’s activism initially began on Facebook. She then decided to participate in the first protest on 21 November 2020 wearing a student uniform – a symbol representing what has happened to her in the past – and holding a banner declaring that she had once been sexually harassed by someone she called a “teacher”.

In reverse, she was harassed again, this time by police officers, who were supposed to protect the people. What’s worse, the event has occurred more than once.

“When I first joined the protests, the uniformed officers might not know who I was. So, I got catcalled.”

“There was a period when I wore a maid costume to attend the mob fest activity at the Democracy Monument. I led a campaign accepting donation for the surgery allowance for public teachers, which was not covered by the 30-Baht scheme. An officer approached me and said something like, “hey, I would like to donate. Can I put it in? Not in the donation box, however. Somewhere else”. When he finished, he turned his gaze to my breasts. My friend witnessed the officer’s gesture as well.”

“Another incidence took place at the protest in front of the Yannawa Police Station, where the We Volunteer guards were arrested. I recall asking an officer to use the bathroom, but he refused. He asked me to show him what pictures I had taken with my phone.”

“I tried to dodge, but he said, “why do you have to bring your phone with you to the bathroom? Leave it with me”. Then, he squeezed my wrist. I got very scared and asked him to let go as I had panic disorder and could not control myself. I did not know what to do, so I cried and screamed. Shortly after, another police officer came to put his arm around my shoulders and pulled my head to his chest trying to console me, saying that there was nothing to be scared of. He pulled my body in even more tightly, which made me cry and scream even louder.”

“What happened at the Yannawa Police Station continued to haunt me for a while. I dreamed of the event many nights in a row for some time. It made me feel like police are not the protectors of the people any more. Eventually, if there is any problem, I don’t think I would have the courage to ask the police for help.”

Nowadays, harassment by authorities is not the only nightmare Muay faces. Since the first day she decided to put a step into the movement and voice out harassment stories, she has become a target of vicious cyberattacks. And as a woman, the insults have never extended far beyond her body.

“Beyond the protest sites, I also face online harassment. People comment that I was a whore, that I got paid to come out. One person sent me an image of a guy licking a female sexual organ to my Facebook inbox, asking, “do you also want something like this? But for girls like you, I won’t even pay 1,800. I think 1,500 is even too expensive.” I come across this stuff a lot since I joined the movement.”

Nan (alias) – political journalist and former political activist

Nan was a political activist. After graduation from the university, she decided to pursue a career in political journalism as a new wave in the media circle. However, as part of her duty to observe protests, she often becomes a target of state authorities. This has led to harassment that almost turned into a long-term mental scar.

“What happened to me took place between the first ‘Mob Tung Ting’ and the Hamtaro-themed protest in 2020. I went in between police officers and a young female activist, who was a newbie and had never handled authorities.”

“Soon after, a guy in crew cut came to take pictures of me closely in an obvious way. I felt it was not right, so I told him off. I remember he claimed that he was not a policeman, that he was just taking pictures of me for fun. He also claimed that he was a taxi driver. However, it was very clear that he was an officer because of the haircut. I just let it go because I had to continue with the reporting.”

“After the incident, some senior activist introduced me to a high-ranking plain-clothed police officer. I complained to him about the officer who took pictures of me and told him that I felt uncomfortable. He was rambling about how he was not an officer. I understand that my position is rather vague, as I am both a press member as well as a reporter, so it is difficult to stop people from taking pictures of me.”

“I think that it is probably fine if an ordinary person or a fan takes pictures of me. In case of an officer, I feel like it is a serious harassment. Worse still, that officer even denied it. So, I talked with my editor, who suggested that I express my good faith by giving the person my business card next time around.”

“The high-ranking plain-clothed officer, to whom I had complained about this matter, probably had a talk among themselves because on the next day at the Hamtaro protest the same officer who took pictures the day before approached me and said, “Hey, I am sorry to make you feel uncomfortable. Actually, I am not a taxi driver like I told you. I am a soldier.” Then, he showed me his officer card. I was not a seasoned journalist back then, and did not take a picture of his card. I was in a state of panic and afraid. I asked myself why he had told me this?”

“The creepiest thing that came out of his mouth was that he didn’t take the pictures for reporting, but because I was pretty. No matter if it was for reporting or because of my appearance, either explanation was just as horrifying. In my opinion, he probably did it for reporting but he chose to explain to me that I was pretty sounded more reasonable to him than saying it was for reporting.”

“Such a view truly lacks an understanding about gender. It made me feel even more scared. After that, he followed me around relentlessly, which made my work more difficult. He tried to ask me out to a meal and whether I had a boyfriend. He tried to get to know me, even though I did not want it.”

“I decided to follow the editor’s suggestion by giving him my business card, yet that did not stop him from trailing me. I had to ask another person for help pull me out of the situation. When it was over, I felt exhausted and frightened. As I was driving home, I was afraid that someone might be following me.”

“Afterwards, he used his personal number to add me on Line. I did not know anymore if this was actually an order or his own intention. During that time, there were protests everyday. He would ask me all the time if I would attend and on which day. So much so that I just had to stop replying him.”

“In the end, it nearly became a trauma. Everytime I attended a protest, I would be paranoid if I would see him there. I was very scared. It haunted me for weeks. After disappearing for a long while, he told me in a chat out of the blue, “by the way I have quit the army”. So, I decided to block him to completely cut the communication.”

Nan admitted that there was still a mental block that she could not overcome, even though the event took place a year ago.

“What happened to me was not so serious that I had to see a psychiatrist, but I made me feel very upset. In the beginning, I became a paranoid person. I would always look around to see whether I was followed.”

“Nowadays, even though it has been a while ago, I still get chills every time I see someone in a crew cut wearing a mask and looking like him.”

“Looking back, I did not understand why I had to act brave and keep my manner that much. I regret that I did not speak up. It is now too late to track down his affiliation. However, at that time, no one was accepting complaints of harassment like this anywhere.”

Lawyer May – Poonsuk Poonsukcharoen, lawyer at the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights

Apart from the difficulty and complexity of the cases, the challenge attributed to female lawyer’s work undeniably involves attitudes of, mostly male, judicial officers as well. More often than not, certain confrontations are unavoidable when it comes to field work and coordination work with officials.

As a lawyer of the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, May explained that her experience with harassment has happened in two instances: while she was working to provide assistance to clients and when she tried to visit a client at the Rangsit Temporary Prison.

“At the end of last year, there were arrests many days in a row. Almost all the accused were brought to file the cases at the Border Police Bureau in Pathum Thani province. At the Border Police Bureau, I had an argument with an officer about the rights of the clients. I maintained that officers did not have rights to confiscate the mobile phones of the accused. The officer was upset. He tapped his arm on mine and said, “why don’t you help me?”. I felt not ok. We were not close. He just touched my body like that.”

“Another instance took place when I went to the Rangsit Temporary Prison. A correctional officer approached and asked me whether I had a boyfriend yet. I felt this was not related to work, even though he might just be trying to be friendly. It came from an old patriarchal mindset. So, I replied him straightforwardly with, “you should not ask me that question.”

Beyond work, Lawyer May shared with us her opinion about gender-based violation or harassment that female activists face, be it by authorities or people with different political stance. Previously hidden in the dark corner of the society, these stories have only been recently brought up in open conversation.

“In the past, women might not have been encouraged to talk about their own rights as much as today. There are now bodies of knowledge that explain women’s rights in various ways, which allow women to dare speak up about their experience. At the same time, they have made people who lack understanding regard these female activists as pernickety. This is the first thing they are labeled with.”

“One more thing, if we compare between the two, female activists are also attacked on her sexuality, whereas male activists are solely criticized based on their ideology.”

“Say, if you are a female activist and you want to talk about some issue, you will also get sexual comments. In case of one female activist, not only was she violated by someone leaking her personal video clip, she was also attacked and criticized for it. This is not right. It also harms the democratic culture that we are promoting.”

Thanakorn “Petch” Phiraban – youth activist and LGBTIQ+ person

At the end of last year, Petch kickstarted her activism journey by speaking at a small protest outside of Bangkok. As she gained more experience, her arguments become more articulate. They deal with issues inherently related to social structure, such as the monarchy. Unsurprisingly, she repeatedly appears on the stage of many major protests in Bangkok.

In return, she has received many lawsuits, including for violating the Emergency Decree, the Communicable Disease Act, Section 116 of the Penal Code, as well as Section 112.

During her early activism days, she was still a youth below 18 years old. One process that she was required to go through at the Juvenile Court was meeting with a social worker or even a psychologist. She also had to complete multiple rounds of evaluation. One question lingers in her mind.

“On the day I went to the Juvenile Court, I had to meet with a psychologist and a social worker. They handed me a questionnaire to complete. One question that struck me was “have you had intercourse with someone of the same sex?” That is my experience.”

“I asked them why this question was there, was it ok that I did not answer because I thought it was not right. If my case was related to sex, I might be able to understand. But why this question was asked in a political case was unclear to me. So, I decided to not answer.”

One question led to others. In many questionnaires that followed, she did not see a similar question, but rather open-ended, broad questions.

What does this inconsistency show us?

“The fact that they asked me this question was as if there was something wrong with an LGBTIQ+ person. Is it a factor that leads to crime? Other forms that were given to me did not contain that question. They simply asked broadly whether I had had intercourse. The partner’s gender was not specified.”

Sugreeya “Mindmint” Wannayuwat – member of Free Gender Group

participation of a large number of people in the democracy movement. Mindmint was one of the activists that became active around that time. Along with her LGBTIQ+ friends, they formed a group called “Free Gender”. She told us about the stories of her friend who was approached by police officers to obtain information. They used words that clearly reflected gender biases.

“This issue may not matter as much for other people. However, as I work on gender equality, it is a tangible form of violence. Some people may not think it is that serious, but I chose to talk about it.”

“When I was still a new activist, police officers did not know me yet. When I planned to organize a protest, I would have to notify the police. So, they had my personal Line account. After the protest, the police officer would chat me up and invite me to a meal or beer.”

“If you read the police documents, this is their secret work – to treat the person that their supervisor asks them to keep watch to a meal. So, we went together as a team. One of our friends was an LGBTIQ+ person and a little feminine. The police approached him and tried to flirt with him. He still continued to chat with him after that day asking him out to do things or have food together.”

“My friend felt uncomfortable because he did not want to talk to the police. The police told him, “hey, it is not easy to find a man. Let alone a police officer’.” He even sent my friend a picture of his uniform.”

“It was obvious that the police intentionally sought out my friend. Maybe he thought he was an easy target? It was like he was using his sexuality as a bait, thinking that an LGBTIQ+ person might have more needs than others? His way of communication made me feel that way. When we went to have beer together, he would say stuff like, “why don’t you bring that friend of yours to sit with me?” He was treating my friend as a bargirl or something like that.”

Watcharakorn “Sun” Chaikaew – United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration

For Generation Z, the world is no longer solely defined by the concept of “male” or “female”. Their clothing and gender expression can flow boundlessly. It is a kind of equality that is still poorly understood by the society.

Sun, member of the academic section of the United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration, identifies himself as queer and chooses to express it through his unisex clothes. What he has to confront in the still conservative justice system is, first and foremost, the “lack of understanding” in this diverse expression. That has manifested in a language that contains gender biases.

“This incident took place when I was accused of reading a statement in front of the German Embassy. As a result of that, I had to go to Mahamek Police Station many times. One time, I asked to use the bathroom and went into the men’s bathroom. The inquiry officer said, “Oh, so you are a boy? You do look like a girl. Are you not a girl?” It was not a question you should ask.”

“His reaction reflected that officers in the justice system, ranging from police inquiry officer upwards, still lack understanding about gender diversity and rights over one’s body. This is despite the fact that the justice system should involve people from different disciplines and the people in it should have broad understanding.”

“In a sense, I believe I understand his lack of understanding and why he acted that way. That said, society is not supposed to function that way. While I do understand, it still affects my feelings. How I dress a certain way should not lead to certain stereotype. The way I dress should not mean that I want to be a girl. It shows that the officers fail to catch up with the wider world. In fact, we may have to include this in the police reform because people are affected in various aspects.”

Lawyer Klao – Kumklao Songsomboon, juvenile case lawyer of the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights

Since August 2021 until now (mid September), The Thalugaz group has been out protesting at the Din Daeng Intersection. This has prompted more than 200 youths and protestors to be arrested and accused.

In case of a mass arrest, many measures are employed disproportionately. One instance clearly indicates that the police officers lack the understanding about the detainee’s right over their body. Particularly, when they belong to an LGBTIQ+ group.

This is what Lawyer Kumklao from the TLHR has experienced from her work.

“During the #10August protest, I have been notified by a volunteer lawyer to provide legal assistance at the Police Bureau of Narcotics, as an activist had been arrested. He was in an all-boy group. The activist had a masculine appearance; he dressed like a boy, and wore short har. However, he was born female and belonged to the LGBTIQ+ community.”

“During the arrest, the riot control police officers, who were men, made him remove his pants. Perhaps it was for examination. Nevertheless, it was inappropriate to treat the detainees in that manner.”

“This has reflected to us problems related to the mindset and practices of the riot control police. In the training, male officers are asked to search men, and female officers search women.”

“However, in case of the Thalugaz activists, although the children and youths who have come out to protest were generally male, the officers should not carry out the examination by having the detainees remove their pants, regardless of their gender.”

“Such behavior is a disrespect to their human dignity. It makes detainees feel humiliated and ashamed. Especially, in case of children, the arrest or search must be done gently, take into account their human dignity, and must not humiliate them like this.”

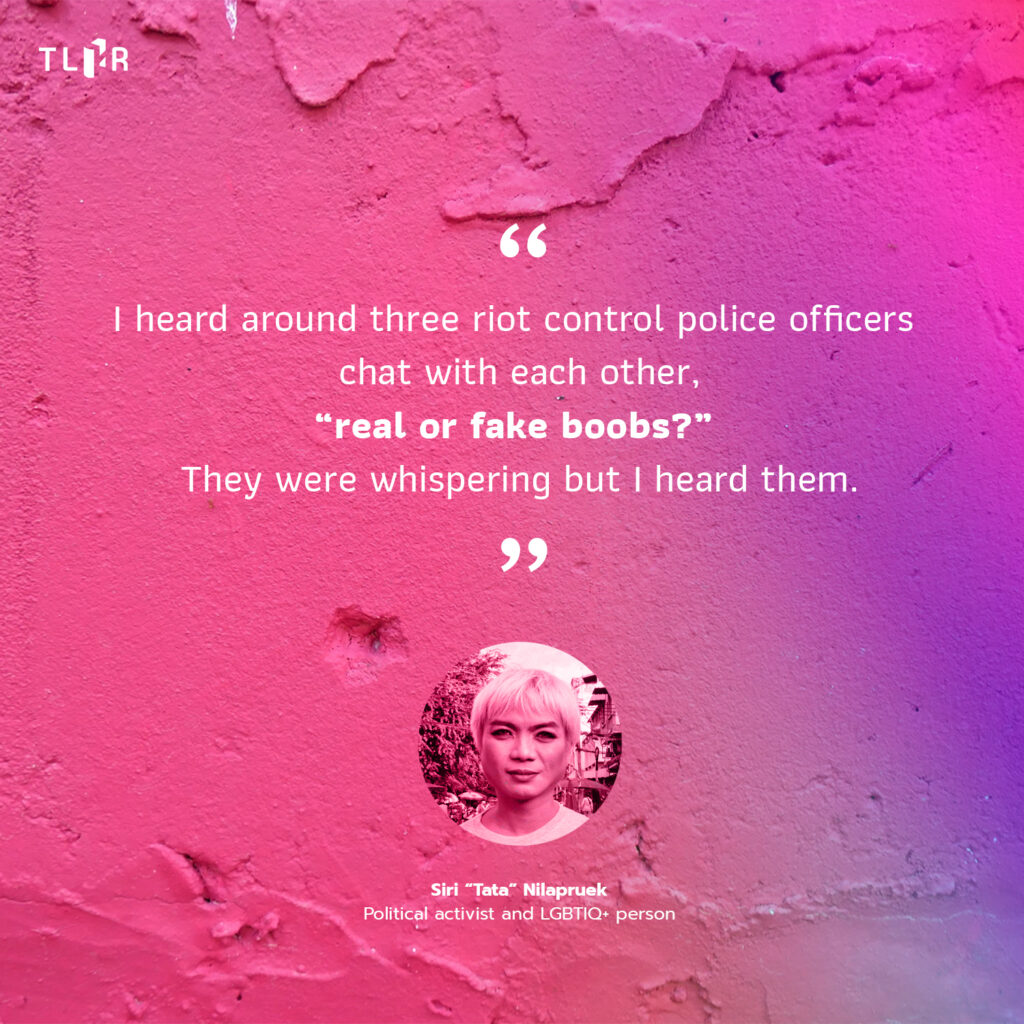

Siri “Tata” Nilapruek – political activist and LGBTIQ+ person

Verbal sexual harassment is common in the society. However, once those words are uttered by law enforcers, we should ask ourselves what kind of society we are living in.

Tata is a social activist that advocates for the rights of the homeless, who has later converted herself into a democracy activist as well. She has shared with us an event that happened to her on 17 October 2020 at the protest at the Ratchaprasong Intersection. She witnessed authorities, who were supposed to enforce the laws, verbally harassed protestors that were still young girls.

“It started when a group of riot control police was setting up force near the Erawan Shrine. I was standing with a group of girls, who assembled to form a human barrier to shield the outer perimeters of the protest.”

“Then, I heard a high-ranking police officer give a clearance order. The riot control police began to move nearer. The human barrier was still there. I was at the front with the girls on my left and right. I heard around three riot control police officers chat with each other, “real or fake boobs?” They were whispering but I heard them.”

“They were not just talking, but giggling too. The riot control police also commented on the body of the girl next to me. They said, “what big boobs”, something like that. I was not the only one who heard it. Many people there did. Then, he gave a sly smile before bursting out laughing.”

“As a human rights worker, that was sexual harassment. I yelled at them in response, “what you said is regarded as sexual harassment against her”. He turned to me, but I did not push it further, as I was concerned for the safety of the girls that were there with me.”

“Personally, I am strong enough to fight back. When I heard that, I could not stand it. However, I tried to contain my emotions and not to quarrel with them, which might cause harm to the girls. Those who also heard it turned downright quiet.”

“The words of the authorities show that they do not understand about other people’s right over their body and have patriarchal attitudes. Given that mindset, they do not feel guilty what about they say. It may be things that they are used to saying. However, it is a form of harassment, even though you do not use a weapon.”