On 12 January 2020, Thailand witnessed the first nationwide assemblies expressing public opinion since the NCPO era, namely the “Run to Oust the Uncle or Run Against Dictatorship (RAD)” running events held concurrently in 39 provinces. In addition to raising awareness about the benefits of exercise for individuals’ wellbeing, participants saw the run as a symbolic expression of opposition to the NCPO’s proxy government and its premier Prayuth Chan-Ocha.

The event was initially conceived by college students and activists who called themselves the “Organizing Committee of the United Federation Front for the Run Against Dictatorship for Democracy and Human Rights in Thailand”, with Thanawat Wongchai, or “Ball”, a political activist and also a student from the Faculty of Economics – Chulalongkorn University, as leader. On 23 Nov 2019, he officially announced the running event and encouraged people to join simply for the sake of their health, as well as to symbolically oppose “the impediment to the nation’s development”.

Despite state authorities harassing and intimidating the organizers (the same tactics used to suppress political movements under the NCPO), RAD activities were for the most part successfully held in almost every province.

While these running events may be considered some of the most visible and significant expressions of public political opinion, they also highlight the ongoing use of state power to subdue movements from the civic sector, even after the disbandment of the NCPO. In this detailed investigative report, Thai Lawyer for Human Rights (TLHR) devoted ourselves into compiling an overview on the obstructions and interventions by state authorities and relevant government-related agencies to the rights and freedoms of runners who merely wanted to express their national political concerns through joining the Run Against Dictatorship event.

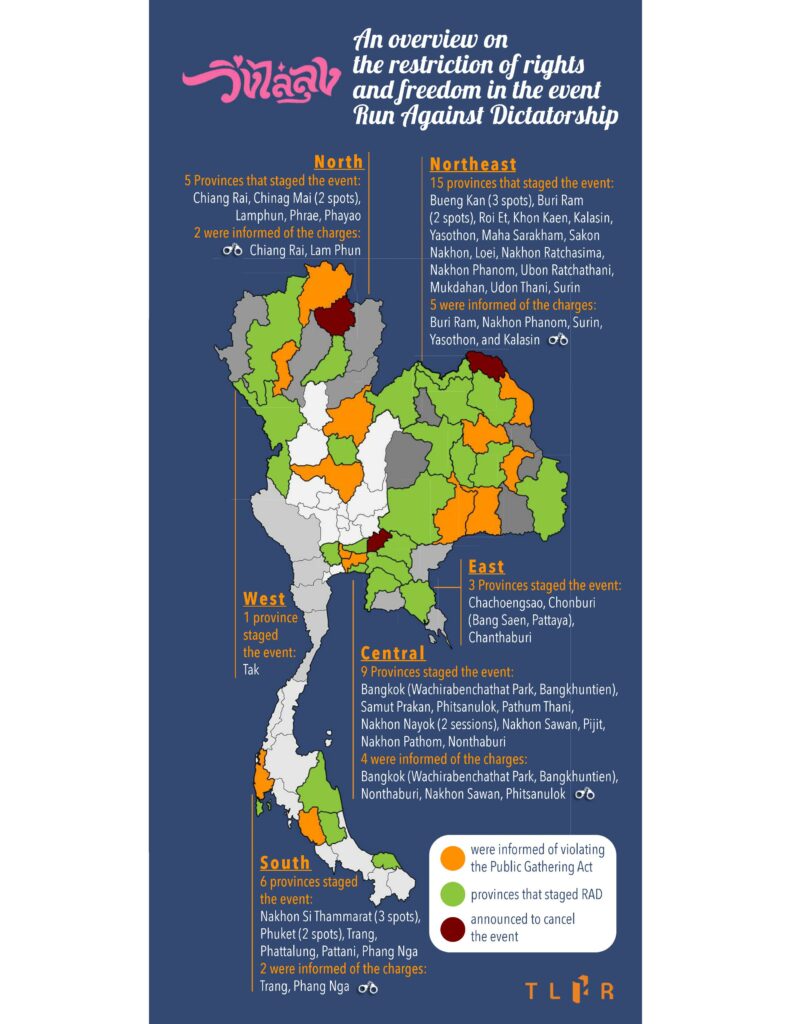

An overview of the people rising up to run in over 49 provinces throughout Thailand.

According to data documented by TLHR on 12 Jan 2020, RAD was staged in 49 locations in 39 provinces.

| Central region: 9 provinces, namely Bangkok (2 locations), Nonthaburi, Nakhon Pathom, Nakhon Nayok (divided into 2 sessions), Pathum Thani, Samut Prakan, Nakhon Sawan, Phitsanulok, and Pijit Northeast region: 15 provinces, namely Nakhon Ratchasima, Ubon Ratchathani, Khon Kaen, Maha Sarakham, Kalasin, Roi Et, Udon Thani, Buri Ram (2 locations), Nakhon Phanom, Yasothon, Sakon Nakhon, Bueng Kan (3 locations), Loei, Surin and Mukdahan. Northern region: 5 provinces, namely Chiang Rai, Phayao, Phrae, Chiang Mai (2 locations) and Lamphun Southern region: 6 provinces, namely Pattani, Nakhon Si Thammarat (3 locations), Phang Nga, Phuket (2 locations), Phatthalung and Trang Eastern region: 3 provinces, namely Chon Buri (2 locations), Chanthaburi and Chachoengsao Western region: 1 province, namely Tak

|

Referring to the information presented above, it is clear that the running events were held extensively in almost every area throughout Thailand, with participant numbers ranging from less than a hundred to more than ten thousand in the Bangkok area specifically. Our limited workforce constrained TLHR from precisely determining the numbers of nationwide participants on 12 January, but according to one report from the Isra news outlet, the overall number of participants across the country was only 14,000 – 15,000 individuals, as measured on-site by “State Security Agencies”. It is important to note however that this figure was determined by state officials alone.

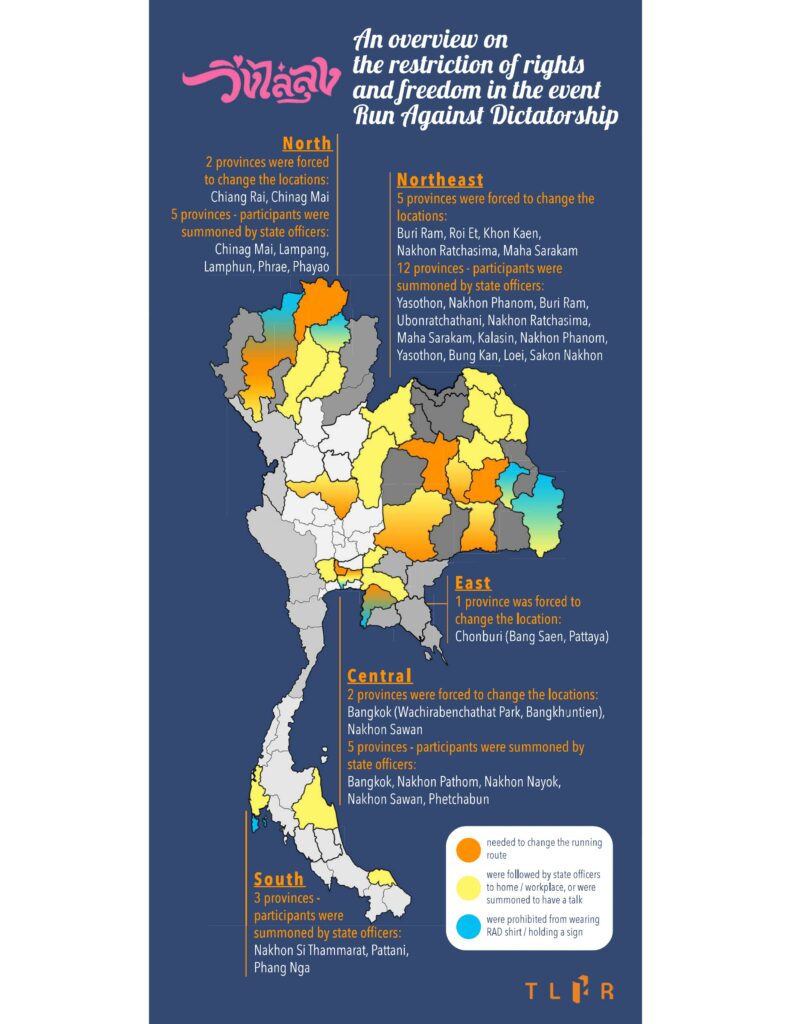

State authorities summoned RAD organizers to have a dissuasive discussion: Four locations had to cancel the event while another 14 had to be relocated.

There were four locations in which organizers had to cancel the event, namely Phayao, Nakhon Nayok Province (the morning run), and two locations in Bueng Kan – Seka District and Bueng Khong Long District.

In 14 areas, including Bangkok, Bang Khun Thian (Bangkok), Pattani, Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Fang District, Nakhon Sawan, Pathum Thani, Pattaya, Nakhon Ratchasima, Khon Kaen, Maha Sarakham, Roi Et and Buri Ram, although there was no apparent attempt made to intimidate organizers, state officers ordered them to relocate the event location, for example to a suburban park instead of an initially-designated downtown area.

Reasons for the relocation or alteration of running routes include: organizers prohibited from using facilities by university or state officer orders; being blocked or discouraged from using originally-appointed event locations; being asked to reroute the run due to traffic or tourism concerns; pressure put on owners of the original event location; and overlapping activities staged by government agencies in the same areas.

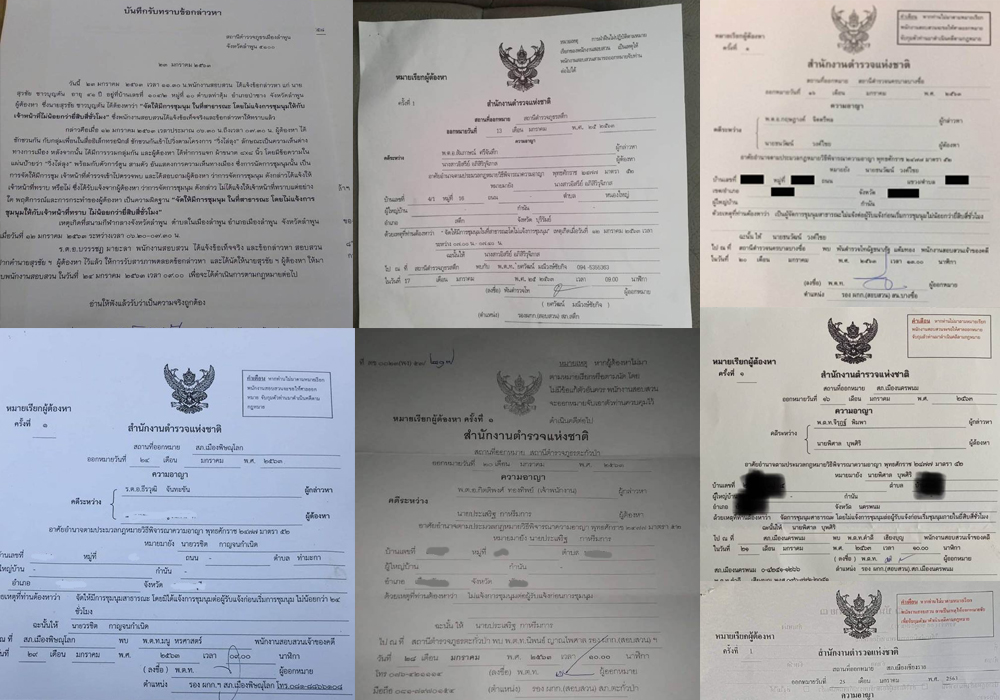

According to data collected by TLHR, organizers or suspected organizers of at least 23 groups were summoned to meet state officers prior to the event.

Police officers enter the home, pressure family members and employers.

In addition to making appointments to contact individuals or issuing a police summons, police officers also pursued event organizers or attendees at their home or workplace. Talking to people in their homes is a more intimidating threat, as there is no advance appointment and it provokes fear in the family or workplace.

According to TLHR’s data, 49 people were followed to their homes or workplaces by state officials around the time of the event. In cases in Buriram, Kalasin, and Phayao, those reportedly intimidated by officers were high school students and university students, some of whom were engaging in public activism for the first time.

In Phrae, Nakhon Sawan, Ubonratchathani and Trang the events were held successfully, despite intimidation and pressure put on organizers prior to and during the activity.

Conversely, the RAD organizer for Nakhon Si Thammarat had to announce to cancel the event after police monitored his house for three consecutive days and requested that he step down as event organizer. Despite the announcement, however, participants did show up on the event day at the originally planned location outside Wat Phra That.

Intimidations to dissuade people from participating in the run.

The same form of intimidation in the form of home visits was used on people who made RAD-related social media posts or applied to join the run in several provinces including Chiang Kham District – Phayao Province, Long District – Phrae Province, and Phang Nga Province.

In Sateuk district, Buriram province, on the day prior to the event, around 200 police officers were reportedly distributed to monitor every resident suspected to be an event organizer. They came in a group of three or four also to speak to groups residents to dissuade them from running on 12 Jan 2020 and threatened them with lawsuits should they attend.

Furthermore, ongoing “target groups” of state officers, including former members of the “People Who Want an Election” movement, reported that they had been visited at home by police officers who tried to dissuade them from participating in the run. These residents also said they were put under 24-hour surveillance or were called by authorities to check whether or not they would join the event. The officers simply claimed their “Boss” had ordered the inquiries.

Intimidation and harassment of former MP candidates and FFP members, despite no announced attendance of the RAD.

In many provinces, former Future Forward Party (FFP) MP candidates were subject to surveillance by state authorities, including in provinces where there was no official announcement inviting people to join the event. Forms of intimidation and harassment included approaching targets to take photos of their home without asking for permission; visiting targets’ homes to ask whether or not they would be joining the event; calling for periodic updates; and close surveillance.

Former FFP MP candidates in Phetchabun, Lampang, Phetchaburi, Nakhon Pathom, Buriram, Nakhon Phanom, and Yasothon provinces reported that they were followed to their houses or workplaces by state authorities.

One notable case of more serious intimidation concerned FFP MP candidate in Lampang. According to TLHR’s information, he was followed by police officers from different divisions who repeatedly asked him for his personal information and details of the RAD event, beginning in the last quarter of 2019. This harassment also affected people close to the target, including his 80-year-old father, who suffers from diabetes, and who had to be hospitalized due to stress after officers made three consecutive visits to their home. In spite of the elderly man’s condition, police officers further pursued him at the hospital to ask more questions. It should be noted that these misdemeanors occurred despite the fact that no running event was planned in that location.

State agencies held concurrent events in the same areas as RAD events.

Although there was no official order banning the public from staging RAD events, authorities found another way to disturb runners in nine areas. TLHR found that there were events and activities hosted by state, provincial, or local agencies in the same areas and at the same times as RAD events, forcing organizers to relocate their events in order to avoid conflict. This occurred in Chiang Rai, Khon Kaen, and Nakhon Ratchasima. In Chiang Mai, organizers and participants persevered with their running activity in the same area as state-sponsored events, which resulted in a critical conflict that curtailed the activity.

Participants in Chiang Mai were disturbed by loud music played through an amplifier and water spray from fire engines as part of a government anti-pollution campaign. This meant that runners arriving at Tha Pare Gate after finishing their lap were soaked in water, causing conflict between runners and state officials and resulting in the run being cut short.

Referring to the Royal motorcade and dispersing news to “discredit” RAD.

The Royal motorcade became an issue state authorities in Chiang Rai used to prohibit runners from participating in the RAD. Although the organizer tried to negotiate with the police to re-route the event, police officers refused to grant permission, claiming that the Royal motorcade might shift from its originally-appointed route, and anyone who caused a disturbance would be prosecuted.

On the day before the event, the Chiang Rai Provincial Police Station published a warning to those intending to join the run, stating that by joining the activity participants were at risk of violating the law and could be prosecuted under criminal charges. Pressured by the authorities, the organizer decided to relocate the event abruptly at 3 AM, just a few hours before the start, to a park, with no public road routes.

Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC)’s role in RAD interference.

In some areas, there were reports that ISOC, including military officers, took part in committee meetings to monitor RAD events or were key agents in approving or denying requests to stage events. This is despite the fact that such activities are clearly out of ISOC’s and the military’s jurisdiction, as RAD has nothing to do with “national security matters”. Such cases were reported in Nakhon Ratchasima, Chonburi (Pattaya) and Pattani Province.

In Pattaya, Chonburi, ISOC’s role in dictating decisions related to the event was alluded to in the response from the Pattaya Provincial Police Station to Anurak Jenwanich, political activist and event organizer, after he had sent notification of the run. The Provincial Police Station’s reply stated that in considering the conditions for staging the event they had arranged a committee meeting, inviting relevant agencies including the Pattaya Municipality, Bang Lamung District, Chonburi Special Branch, and officers from the ISOC. However, the letter did not specify what legal authority, if any, was invoked to invite ISOC to join the committee.

In the conflict-ridden southern province of Pattani, ISOC had immense power to dictate decisions regarding the running events. According to reports, military officers pressured the imam of the Central Mosque to deny runners permission to use the location as a gathering place, claiming this order came directly from Lieutenant General Pornsak Poonsawat, Commander of the Fourth Region. In many other regions, plain-clothes military officers were reported to have been presented and closely monitoring the run.

Universities and local authorities and their roles in restricting the right to participate in the RAD.

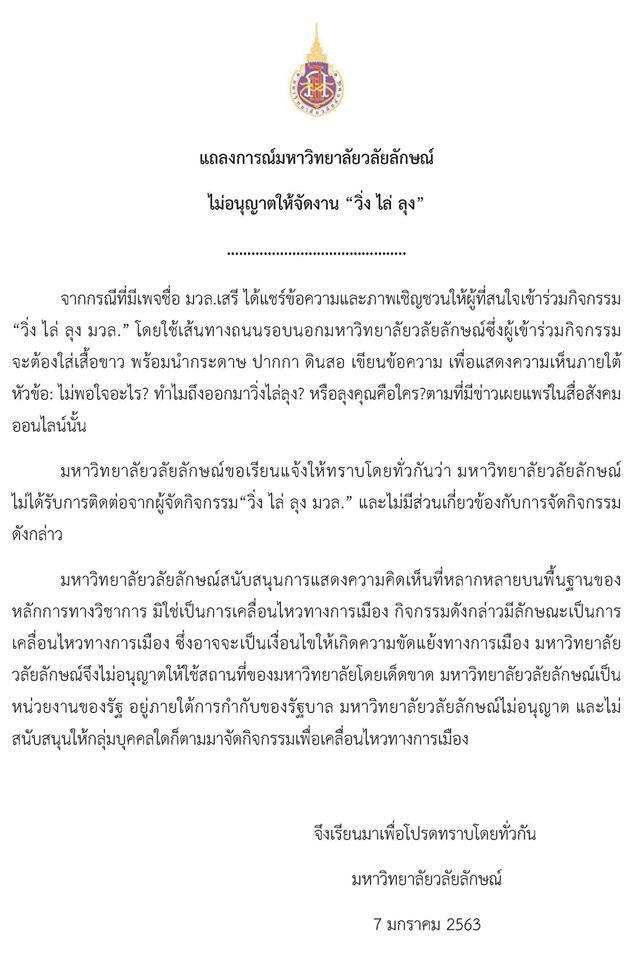

Outside of official restrictions made by military and police officers, several universities played a role in impeding students’ rights to participate and organize the RAD on campus, including at Walailak University, Khon Kaen University, Maha Sarakham University, and Burapha University, Chonburi.

One such case occurred at Walailak University, where university students announced that they would host the event on campus. To counteract, the university made an official public announcement prohibiting the event, claiming it served a political movement. University officers further obstructed students’ right to participate by summoning students to talk to police officers and dissuading them from making any further attempt to host the run.

Unabated by the intimidation and restrictions, the student organizers successfully managed to continue with the run. Shortly after however, four of the organizers’ names were removed from the university’s Center for Drug Prevention and Suppression of which they had been members, stirring public criticism of such unjustified conduct by university officials. After this backlash, the order to remove the students’ names was later revoked. The harassment became more pervasive when university officials divulged the students’ personal information via the Line social media application, seriously violating their right to privacy.

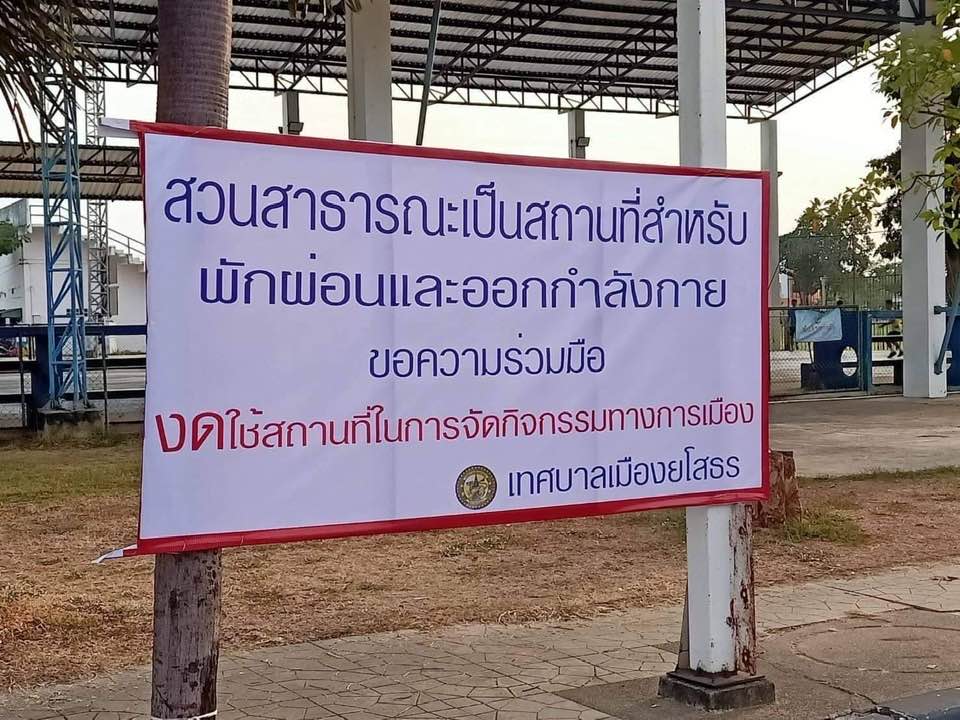

Individuals’ rights were also restricted by the local governing agencies which oversee the maintenance of public facilities, in particular parks and sports venues. In three cases (in Phrae, Chiang Rai, and Yasothon) event organizers faced difficulties in acquiring permission to use parks or were asked to pay a fee to use the area to stage the running event (in Yasothon).

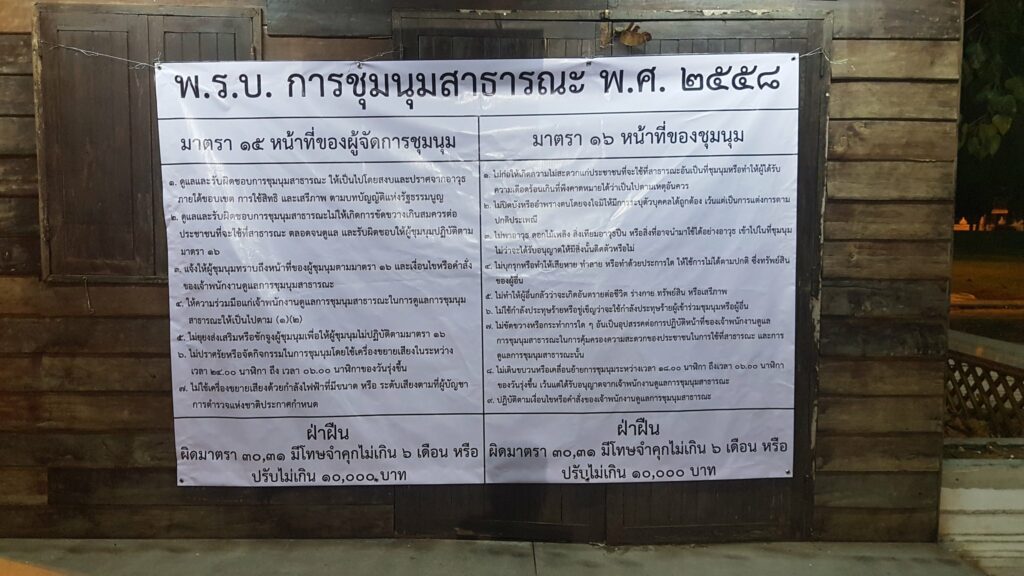

Unethical use of the Public Assembly Act and obstructive conditions imposed by authorities.

RAD organizers and participants in several areas encountered difficulties from unethical uses of the Public Assembly Act to curb individual rights and freedom of expression. One such use was ordering organizers to request state authorities’ permission to stage the event, in contravention to the specifications of the Act, which merely requires organizers to “notify”, not seek permission from authorities. Another tactic was imposing conditions on the event in order to limit those intending to participate. This pattern of restrictions occurred in Ubon Ratchathani, Chonburi (Pattaya), and Chachoengsao (Bang Pakong).

Incorrectly defining the running activity as a political gathering.

Article 3 (3) of the Public Assembly Act states that any gathering for public participation in a sporting event shall not require the organizers to notify the event to the authorities. Under this definition, the RAD should be considered a sporting event just like any other event with a social campaign to raise awareness of a particular issue. In reality however, organizers in many areas who failed to notify the event to authorities were and continue to be pressed with police charges (as of documentation on 28 Jan 2020). The total number of individuals charged with failing to give advanced notification of a public assembly has soared to 17 cases in 13 provinces: five in the Northeastern Region (Buriram, Nakhon Phanom, Surin, Yasothon and Kalasin); four in the Central Region (Bangkok, Nonthaburi, Nakhon Sawan, and Phitsanulok); six in the Northern Region (including Lamphun and Chiang Rai); and two in the Southern Region (Phang Nga and Trang).

In the cases where organizers were charged under the Public Assembly Act, extrajudicial measures taken by the police officers have also been reported. Namely, officers reportedly made direct contact to summon individuals to hear their charges at the police station when there was no official summons, or coaxed individuals to confess and pay a fine accordingly (as occurred in Yasothon).

Using laws concerning the use of amplifiers and land traffic to fine organizers.

In addition to the Public Assembly Act, other laws and misdemeanor charges were used to suppress the events, such as the restrictions on using an amplifier in public without permission and on using a road traffic surface without permission. Despite their minor penalties, such laws are a financial and time burden to organizers having to travel to the various responsible agencies merely to request permission to use some equipment. This method of restriction was reported in four provinces: Kalasin, Phrae, Trang, and Nakhon Sawan.

Pressure from the counterreaction group to support the government.

Judicial harassment was not the only form of intimidation. There was also pressure from the counterreaction group who called themselves “Cheer Uncle” (meaning support the Prime Minister). Although this opposition gathering came about through individuals’ constitutional rights, this political participation was used as an excuse by authorities to block RAD events on grounds of public opposition, thus suppressing RAD organizers, rather than protecting their rights. In some cases, there were reports of police officers instigating face-to-face encounters between the two groups, increasing the likelihood of violence. This form of intimation was reported in Phayao, Buriram, and Bangkok.

In the case in Phayao, when RAD organizers came to heed a summons to the Phayao Provincial Police Station, a pro-government gathering was outside with supportive banners, calling for the RAD organizers to stop “disturbing” Phayao residents. A police officer then brought a student from the group of RAD organizers to talk with the opposing gathering, trying to dissuade the student from staging the event as there were people in the area who did not agree with the RAD organizers. This encounter is all the more concerning due to the fact that the organizers’ visit to the station was never publicly announced in advance.

Signs and banners prohibiting people from using public space to stage an event.

Another common form of restriction of freedom of assembly was the use of signs and banners with messages clearly prohibiting runners from using the public space; such cases were reported in Sakon Nakhon, Yasothon, Sisaket (despite there being no planned RAD), and Nonthaburi.

Deploying large numbers of state officials to monitor and document the runners closely.

Large numbers of state officials and plain-clothed officers were mobilized to monitor RAD participants in several areas during the events. In some areas, the number of state officials even exceeded the number of runners, while strict security measures were also taken onsite. These included taking photos and recording videos of individual runners and holding a checkpoint at the entrance to the event to screen the runners.

A critical case was reported in Pattani, which saw the strictest level of surveillance due to security concerns. State officials used weapon detector machines and took individual photos of each runner, causing the event to start later than the designated time.

Similar cases of intimidation were reported in Nakhon Ratchasima, Yasothon, and Phattalung (in this province, the number of state officials reportedly exceeded the numbers of runners; according to one observer, during the event on 12 January there were around 200 state officers, including plain-clothes officers, and only around 150 runners).

State officials prohibiting runners from holding signs and banners and wearing RAD shirts.

Intervention by the state authorities was so pervasive that they also banned runners from holding signs or banners with even subtle political messages and, in some cases, banned runners from wearing RAD shirts during the event. According to TLHR’s documentation, these types of restrictions were imposed in seven areas, including Bangkok, Fang District in Chiang Mai, Phayao, Ubonratchathani, Phuket, and Yasothon.

In Phuket, one report revealed that officers also came to pressure a T-shirt store not to produce an order from event organizers for T-shirts with the RAD logo. The order was then canceled as the store owner did not want any trouble with the authorities.

Hurdles on the track and the remains of authoritarian influence.

Undeniably, the attempts of state officials and relevant government agencies to hinder, intimidate, and intervene in RAD events nationwide restrained the public from RAD participation, whilst also leading people to believe that joining such activity amounts to a crime.

The use of state power with regard to the nationwide Run Against Dictatorship can, therefore, be considered an organized means to suppress the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. Such violations of the rights of politically active citizens have continued since the 22 May 2014 coup until today, regardless of the fact that Thailand now has an elected government in the office and the NCPO is no longer in power, at least ostensibly.

Whilst there has been a change of tools used to suppress civil movements (for example, the repeal of the Head of the NCPO’s order barring political gatherings), the tasks of dubious law enforcement and threats to freedom of expression have simply been passed on from military to police hands. The primary methods, however, persist: house raids, summoning individuals for a ‘chat’, using ‘state security’ as a pretext to curtail political expression, intervening in and directing political gatherings, blocking the public from using public spaces. These abuses all prove that the state’s arbitrary use of authoritative power is as much alive today as it was under the NCPO.