What has happened in the past five years?

On 22 May 2014, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), led by Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha, seized power from the Yingluck Shinawatra government, revoked the 2007 Constitution, imposed martial law and arbitrarily issued a string of announcements and orders to rule the country as it deemed fit.

Five years ago, the 2014 Interim Constitution was promulgated. The Section 44 of the Interim Constitution gives the Head of the NCPO the authority to issue orders effective in legislative, executive, or judicial matters. Any order or act made by the junta leader is considered lawful, constitutional and final. The 2014 Interim Constitution has since been replaced by the 2017 Constitution which was voted for in a referendum amidst mass arrests of those who campaigned against the Draft Constitution.

Despite the promulgation of the new Constitution, the current form of the parliament has regressed to resemble that in place 28 years ago. Furthermore, people had to wait another two years before the election date was finally confirmed. Now, Thai citizens are sceptical about the election results and the questionable performance of the Election Commission of Thailand (ECT), owing to which the identity of the next Prime Minister remains unclear.

Until now, thousands of people have been subject to harassment, deprivation of liberty and trial in the Military Court. Hundreds have been charged and barred from expressing their views. Dozens more complain about torture while in custody.

For the past five years, the people of Thailand have suffered.

Announcements/Orders and laws made during the reign of the NCPO

In the past five years, the NCPO has issued 132 NCPO Announcements, 214 NCPO Orders and 207 Head of the NCPO Orders, invoking Section 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution, and imposed them on the people. Such Orders and Announcements issued by the coup makers are incompatible with democratic values and the rule of law, and with the rights and freedoms of individuals in particular. They have given rise to unlawful detention, making people vulnerable to torture and enforced disappearance and depriving them of their right to fair trial. Yet such decrees have been made lawful and given the leaders impunity in the era of the NCPO.

Moreover, the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) appointed by the NCPO has enacted 444 laws, many of which have been rushed through, despite containing restrictions to people’s rights and freedoms. The coup regime has imposed a string of laws, far more than were enacted after the 19 September 2006 coup. The coup makers at that time, the Council for Democratic Reform (CDR), decreed just 34 Announcements and 18 Orders prior to the promulgation of the 2006 Interim Constitution, after which they stopped invoking their power to issue more laws.

These Announcements, Orders and laws have given rise to the incessant violation of human rights throughout the past five years.

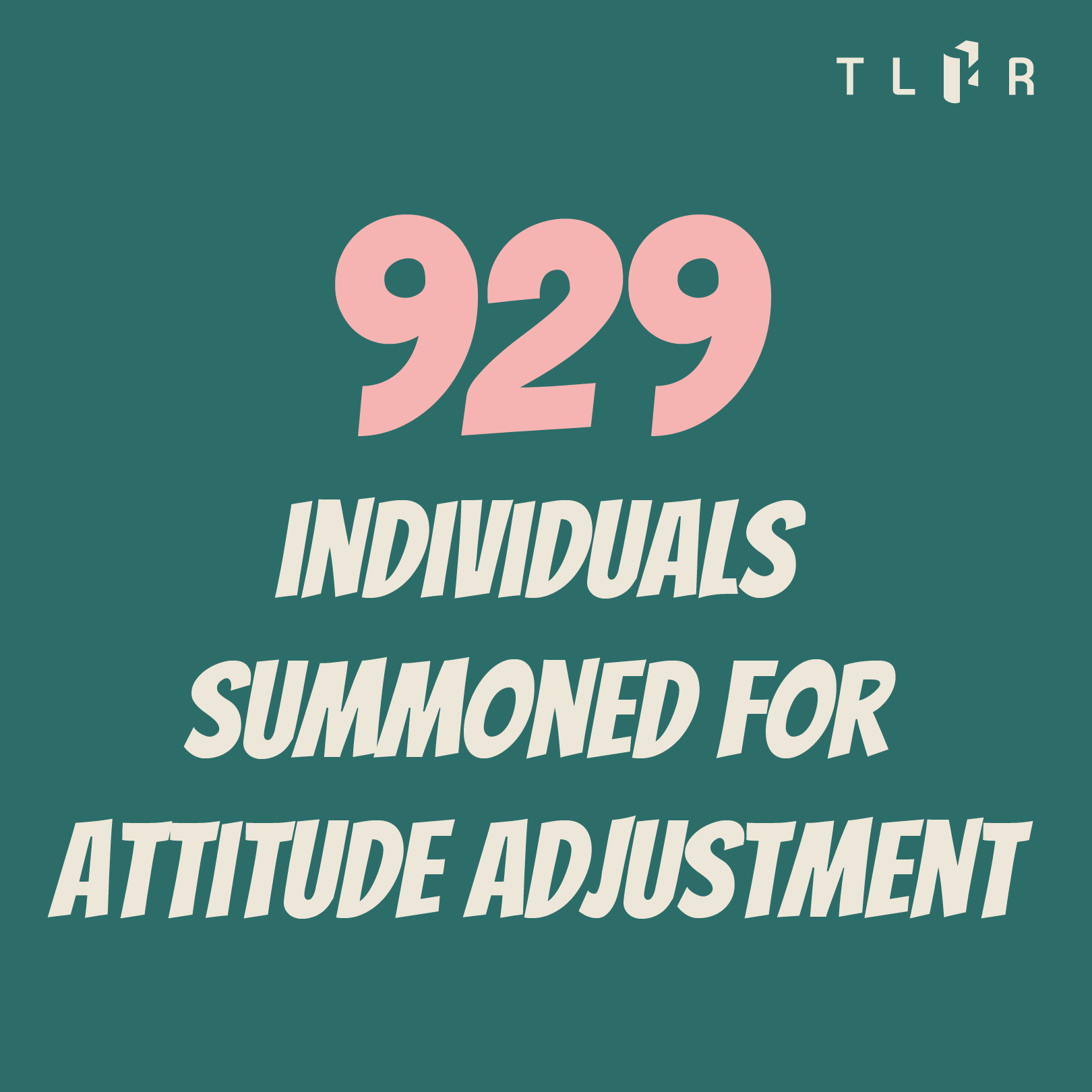

929 individuals summoned for attitude adjustment

In the first year after the coup, the NCPO imposed Martial Law from 20 May 2014 to1 April 2015, bequeathing more power to military personnel, who consequentially became more powerful than civilian officers. This allowed for detention of an individual for up to seven days without charge and without a court arraignment. After Martial Law was lifted, the Head of the NCPO continued to invoke Section 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution to issue two major Orders: the Head of the NCPO Orders No. 3/2558 and 13/2559. These bestowed extra power to military personnel, enabling them to act as competent officers and executors of Martial Law. These Orders and Section 44 have since been invoked every time the authorities carry out an arrest and detention of individuals in military barracks, or when conducting a search of the private residence and/or workplace of a targeted person or his or her family members.

For the past five years, at least 929 individuals have been summoned by the NCPO to report themselves and have been detained in military barracks without access to their families and lawyers, and without charges. This is the so called “attitude adjustment” process. At least 14 of them have been charged for defying the NCPO summons.

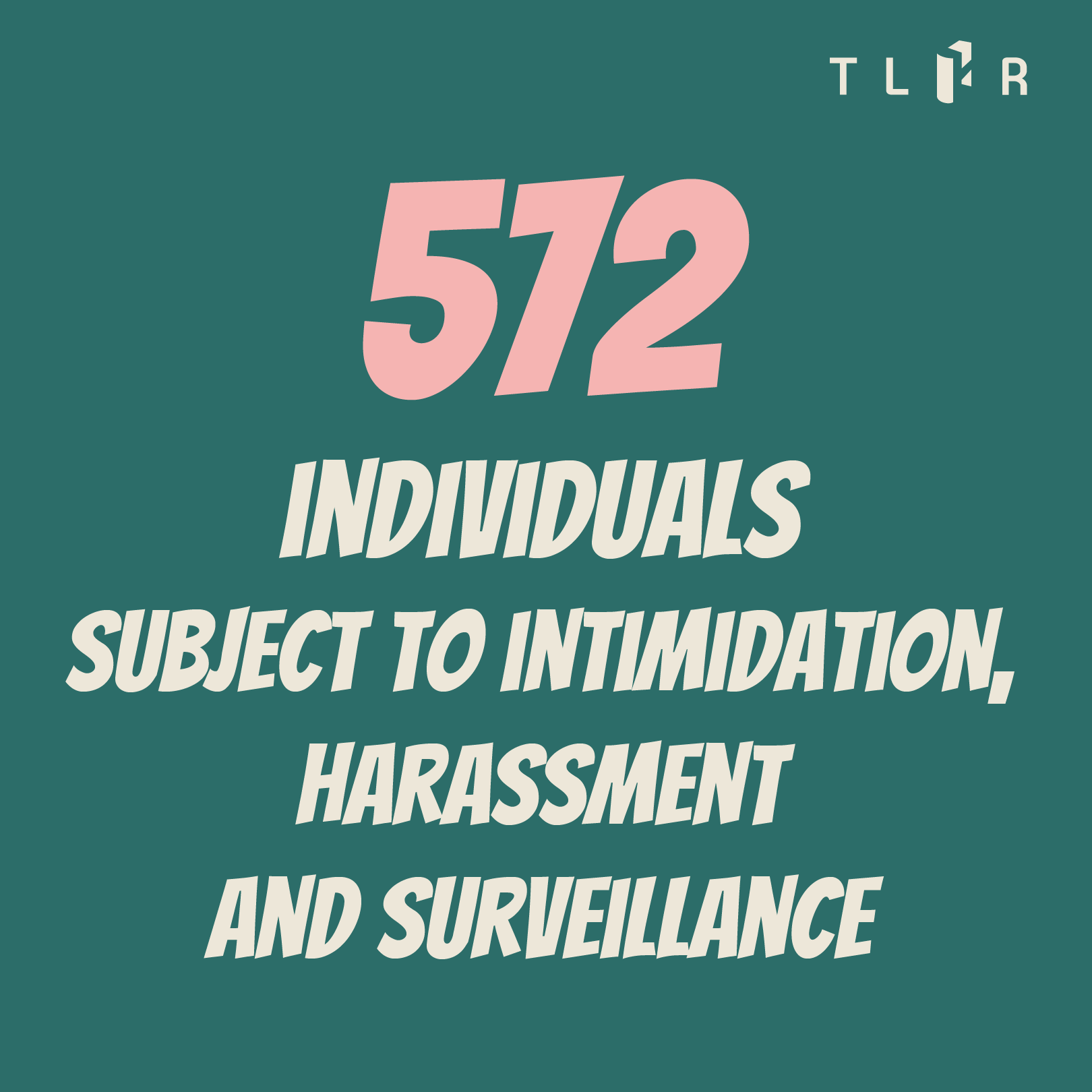

572 individuals subject to intimidation, harassment and surveillance

In addition to summoning people to report themselves and detaining them in military barracks, the NCPO has deployed officers to follow at least 572 individuals. Many of them have been visited at home and put under constant surveillance.

The first two years saw an intense effort to monitor certain individuals, mostly politicians, Red Shirt core members in different provinces, anti-coup activists, and critics of the NCPO or its exercise of power.

The constant blanket surveillance included visiting them at home and taking their photo, asking them to meet for a coffee, or “asking for cooperation” to forgo certain activities and to attend others, including reconciliation activities. The more intense the political atmosphere, the greater the effort and frequency of the surveillance became. For example, restricting the freedom of those who made demonstrations demanding elections; following and harassing politicians before the election day; intimidating individuals who exposed misconduct during the election campaign period; and monitoring and harassing individuals during the coronation ceremony.

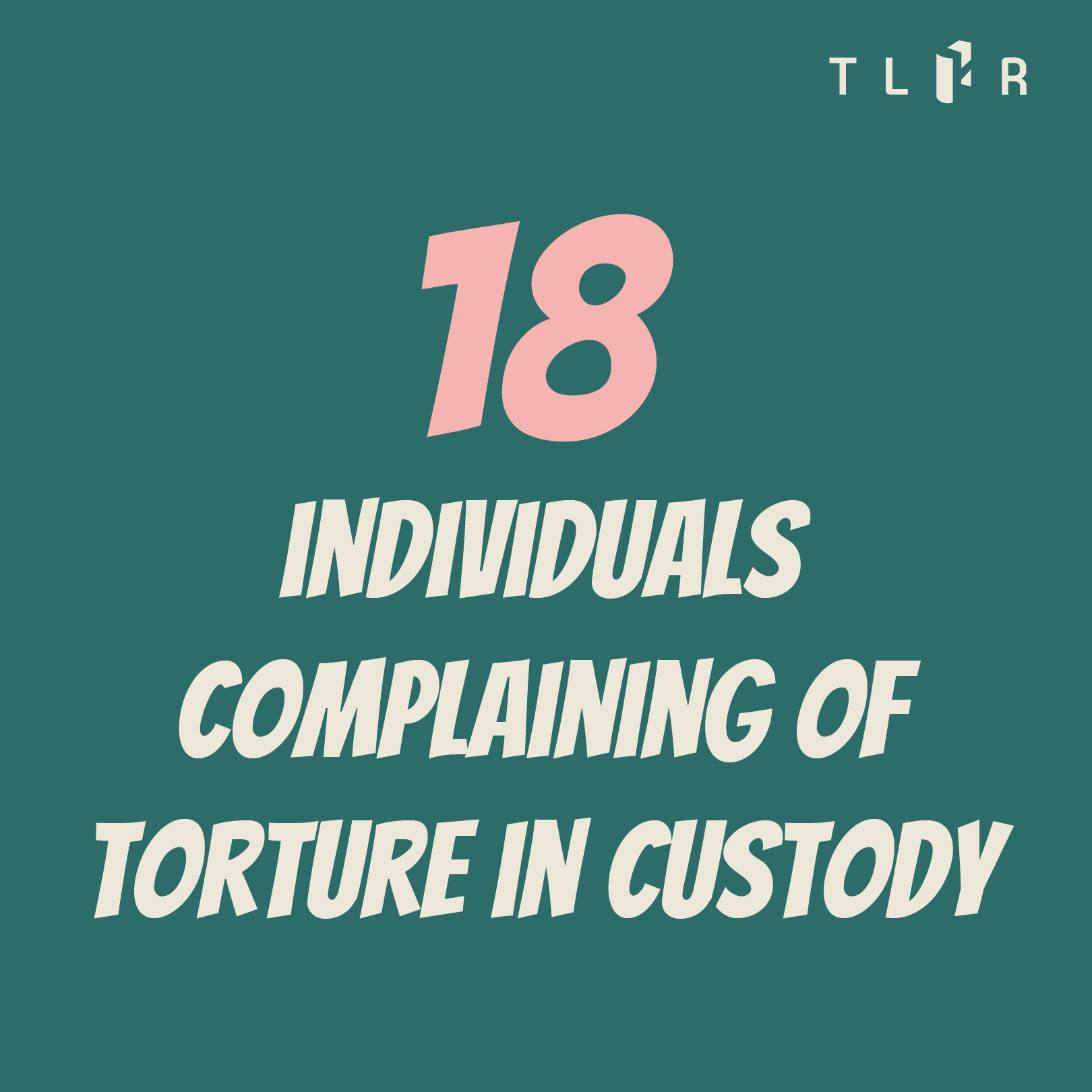

18 individuals complaining of torture in custody

In the aftermath of the coup, the military authorities systematically deprived individuals of their liberties, held them in custody in undisclosed places, denied them access to their families or lawyers and denied them judicial review. This made them vulnerable to enforced disappearance, torture and ill treatment, and subject to the whims of public officials exercising their power arbitrarily.

After the 2014 coup, at least 18 individuals made complaints about torture in custody as a consequence of Martial Law, NCPO Orders or the Head of the NCPO Orders. The most notable case among them is what happened to suspects of the bomb attack at the Bangkok Criminal Court on 7 March 2015. At least four suspects allege having been tortured, including beating, punching, stomping on their heads, chests, backs and threatening to inflict physical abuse on them, simply to obtain information from them by force. Some suspects alleged that they had been tasered and had sustained burn marks on their skin while they were held in custody under Martial Law during 9-15 March 2015.

353 public events intervened in or blocked

In the past five years, 176 public events have been blocked, and another 186 subjects to harassment and intervention, making a total of 353 events. They were shut down mostly because the topics were either about politics or the coup makers. The authorities often claimed the events could be interpreted as political assemblies, which might have caused social division or compromised national security.

In certain cases, the authorities simply cited ambiguous reasons and asked for cooperation from the organizers to cancel the events. They could just say “my boss is not happy” with the event. In some cases, they simply pressured the owners of the venues, universities or private places until the venue owners or administration agreed to ban the events from taking place on their premises.

In cases where events were not shut down entirely, the authorities might talk with the organizers and impose some conditions on or request some modifications of the events. For example, they might press for a change of certain speakers, for issues related to the NCPO to be excluded, or for certain words like “dictators” and “usurpers” to be censored.

At the same time, local military units would approach the administration or faculty members in various universities asking them to restrict students’ activities. They would be asked to notify the local military before authorizing any event. Institutions including universities have thus been used as a tool to restrict students’ rights and freedoms to organize public events, in as far as they would refuse students permission to hold the events, or summon students who organized events for a talk.

Restriction of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association against 155 community-based organizations and civil society organizations

In addition to blockades and interventions in public events, community-based organizations and communities have been affected by various other public policies restricting their right to freedom of expression for the past five years, even though they did not mobilize for political causes in the sense of directly criticizing or opposing the leaders.

According to our documentation, at least 155 community-based organizations / communities or civil society organizations have seen their rights to freedom of expression and public assembly restricted. They worked on issues concerning the environment, forest, land, river, mining, power plants, public health, labour or other public policy issues.

Military authorities have invoked Martial Law and the Head of the NCPO Orders no 3/2558 and 13/2559 to summon core members of the communities for a talk. They have even visited them at home in certain cases. The authorities told the villagers to stop engaging in any activity, claiming the exercise of such fundamental rights would have led to an ‘unrest’, or accusing these core members of being “influential figures.” An effort has also been made to censor educational activities and cultural exchanges. Such acts were interpreted as ‘seditious’ acts against the government. Some individuals were forced to sign an agreement, similar to those signed by core members of political affiliations, to promise to stop engaging in certain activities. In certain areas, the authorities demanded local people remove protest banners.

428 individuals charged in relation to political assembly of five or more people

After the imposition of Martial Law on 22 May 2014, the NCPO Announcement no. 7/2014 was issued to prohibit gatherings of five or more people, the violation of which holds a maximum penalty of one year of imprisonment and a fine of up to 20,000 baht. After Martial Law was lifted, this Announcement was replaced by the Head of the NCPO Order no 3/2558. Article 12 of the Order bans political gatherings of five or more people, the violation of which holds a maximum penalty of up to six months of imprisonment and a fine up to 10,000 baht, or both. The order was only lifted on 11 December 2018.

428 individuals have been charged for violating the NCPO ban on political assembly of five or more people. Many of them were charged as a consequence of their activities during the Constitutional Referendum in 2016 and during the demonstrations to demand elections in 2018.

245 individuals charged for violating the Public Assembly Act

The NCPO-appointed NLA enacted the Draft Public Assembly Act, which came into effect on 13 August 2015. The law has since been used jointly with the Head of the NCPO Order no 3/2558 to restrict the right to freedom of assembly. Enforcement of the Act and its provisions alone has also created many challenges and hampered, rather than protected the right to freedom of assembly. For example, it requires that the authorities must be notified at least 24 hours prior to any public assembly taking place. It also grants the authorities power to change public assembly venues arbitrarily and to impose other conditions. It essentially allows the authorities to prevent public assemblies at their discretion and to impose other overwhelming requirements upon demonstrators, making it impossible for them to organize a public assembly.

Throughout its enforcement, at least 245 individuals have been charged for violating the Public Assembly Act. Most were charged simply for failing to notify the authorities in advance.

144 individuals charged for violating the Computer Crimes Act as a result of expressing their political views

In addition to public assemblies, social media campaigns are another common means of criticizing the military’s exercise of state powers. Consequently, the Computer Crimes Act (CCA) has become a major tool to suppress and harass dissenters.

At least 144 individuals have faced charges for violating the CCA by expressing their opinions or criticizing the NCPO or military authorities in the internet. When reporting these cases, the military claimed such input of computer data had caused damage to the NCPO or to military authorities.

Many have found themselves charged for violating the CCA along with Sections 112 or 116 of the Thai Penal Code. Even after CCA’s amendment in 2017, the situation has not improved. Individuals continue to face charges simply for sharing news which might not have been based on facts, or which contained information critical to the NCPO. In most cases, individuals simply shared the news without adding their own personal opinions. In some cases people fell victim to fake news websites, one example being the sharing of a post from the KonthaiUK Facebook page which criticized a procurement of satellites. Others involved sharing fake news about the Deputy Prime Minister Gen Prawit Wongsuwan and the Election Commission.

121 individuals facing sedition charge

As of 22 May 2019, at least 121 individuals face charges of sedition per Section 116 of the Thai Penal Code, mostly as a result of criticizing the NCPO, i.e., asking the government to hold elections, as in the case of the ‘People Who Want an Election.’ Other forms of expression, not mentioning the NCPO directly but related to the power of the NCPO, i.e. sending a letter to criticize the Draft Constitution or displaying a symbol with a red cup, and being member of the ‘Organization for Thai Federation’, may also prompt criminal charges.

169 individuals charged for defaming the monarchy

In the aftermath of the 2014 coup, the lèse majesté law has been used as a tool to significantly suppress political opinions. It appears that the repression of those expressing their views about the monarchy has been a major policy of the NCPO since its inception.

Until now, at least 169 individuals face the charge, including at least 106 as a result of expressing their views and at least 63 for claiming connection to the monarchy in order to commit fraud. During the reign of the NCPO, the judiciaries have tended to impose heaver sentencing on lèse majesté offences, particularly at the Military Court, which imposes a sentence of eight to ten years imprisonment per charge on average. This has given rise to record jail sentence lengths, including those given to Wichai (sentenced to 70 years), Pongsak (60 years) and Sasiphimon (56 years), all of whom had their imprisonments reduced by a half after pleading guilty.

Furthermore, a broader interpretation of Section 112 has been used to criminalize: a satirical post about a dog adopted by the King; ‘liking’ posts which could be culpable for violating Section 112; failing to prohibit or censor another person who expresses views deemed defamatory to the King (the case in point was Patcharee Chanjit, mother of a prominent student activist, “Ja New”); and claiming connection to the monarchy in order to commit fraud.

2,408 individuals tried in the Military Court

Another major tool frequently used under the rule of the NCPO has been the use of the Military Court to try civilians for four types of offences including offences against the King (mostly against Section 112), offences against national security (mostly against Section 116), offences involving firearms, and offences against NCPO Announcements or Orders.

Even though the NCPO decreed to stop trying civilians in the Military Court as of 12 September 2016, for cases involving offences committed between 25 May 2014 and 11 September 2016 the alleged offenders are still required to face trial in the Military Court. According to the Judge Advocate General’s Department, 1,886 cases against civilians have been tried in the Military Court, involving over 2,408 civilians. Of these, 450 defendants in 369 cases have yet to sit in the dock in hearings conducted by the Military Court.

According to the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), trials by the Military Court are often protracted due to (1) the nature of the offence being related to the coup, (2) the rescheduling of prosecution witness examinations. Such predicaments hamper defendants’ right to a fair and timely trial.

Five years from now

The number of victims of rights violations or politically motivated charges as presented by Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) is based on information up to 22 May 2019. Yet another consequence of these cases is the growing climate of fear. We cannot fathom how many more people have been deterred from speaking their mind by these criminal proceedings. Such prosecutions have made people too afraid to express themselves, to demand scrutiny of the government’s performance, or to oppose any decision which may affect their livelihoods. This chilling effect is the result of constant prosecution throughout the past five years.

Although the NCPO will not exist after the election its mechanisms will remain in place. All NCPO Announcements and Orders and the 997 laws enacted by the NLA will continue to be enforceable. Meanwhile, members of the NCPO and its supporters have morphed into politicians as members of the Palang Pracharat Party. The NCPO has even appointed members of the Senate who will work for another five years.

Member of all other independent agencies which are supposed to keep checks and balances on the government have all been appointed by either the NCPO or the NLA including the Constitutional Court, the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), the Office of Ombudsmen, the Office of the Auditor General and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).

Additionally, the NCPO has appointed its members and supporters as part of the National Strategy Committee, which has the power to outline the strategies all succeeding governments are required to follow.

Given this situation there will be endless number of affected people.

How shall we proceed?

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) has been documenting political challenges, the justice process and the violation of human rights and has processed the information in order to explore solutions to the effects of the coup. TLHR proposes four recommendations including (1) restriction of the armed forces’ powers and reform of national security sector, (2) fair access to the criminal justice process, (3) remedies and compensation for victims of the exercise of state power during the 2014 coup, and (4) management of the NCPO Announcements and Orders, other laws decreed by the NCPO, and court judgments. These recommendations can be interpreted as follows;

1. Restriction of the armed forces’ powers and reform of national security sector

The coup was staged with an aim to cement power in the long run. A process of militarization has ensued, in particular by incorporating the armed forces into the political and constitutional institutions and making them part and parcel of everyday life. This has effectively culminated in the seizure of sovereign power from the people. The armed forces have been used as a means of managing political conflicts and human rights violations. The militarization of the political process has resulted in various actions including classifying certain people as “target groups” and seeing specific civilians as “target persons” of military operations. In this way the military has become involved in law enforcement and the judicial process. Two major recommendations can be proposed as follows;

1.1. Address the coup and human rights violations by the armed forces

1.1.1. Annul legal provisions that bestow immunity on the coup makers, making such immunity void and doing away with its legal implication. This will help ignite a process of holding the coup makers to account.

1.1.2. The security forces and agencies must disclose their information, objectives and their surveillance programs to collect information from the people, as well as details of the information operations, psychological warfare and propaganda, which have been used to manage political conflict since the 2014 coup. Such information must be unveiled to the public.

1.1.3. An anti-coup mechanism must be put in place to prevent more coups in the future and to prohibit military officials from taking posts in the administrative and legislative branches, or in any committees which could wield state powers.

1.2. Rearrange the power structure between the military and civilians through two methods (1) by amending existing legal provisions and (2) by restructuring agencies under the armed forces.

1.2.1. Amend existing legal provisions: this should include the amendment of the 2017 Constitution by adding provisions to place the military under civilian control. The notion of “civilian control of the military” must be made an underlying principle of the Constitution and codified in its General Provisions. The 2017 National Strategy Act must be repealed in its entirety. Members of the Senate must come from direction election of the people. The 2008 Ministry of Defence Organization Act must be amended. The 1914 Martial Law Act and the 2008 Internal Security Act must be repealed.

1.2.2. Restructure agencies under the armed forces by instituting an armed forces inspector appointed by the House of Representatives; downsizing the armed forces; instituting a mechanism to monitor and control the economic power of the armed forces and military personnel; instituting a mechanism to enable the public to access information held by the armed forces or ensuring transparency of the information held by the armed forces; redesigning agencies and organizations involved in national security; enabling a paradigm shift by reorienting the armed forces’ missions from a concept of “national security” to “national defence”.

To ensure concrete and proper adaptation, it is recommended that such transformation be divided into Phase One (short-term): instituting an anti-coup mechanism; Phase Two (intermediate future): armed forces reform by amending the Constitution and statutory laws; and Phase Three (long term): armed forces reform by restructuring agencies under the armed forces and other security agencies.

2. Fair access to the criminal justice process

Access to a fair trial process through the normal criminal proceeding is a major challenge for people who have exercised their rights and freedoms and must stand trial in both the Court of Justice and the Military Court. Since the 2014 coup, the right to fair trial has been stymied as a result of: legal provisions issued to criminalize certain acts; military officials being empowered to be inquiry officials, similar to normal law enforcement officials; and the expansion of the Military Court’s jurisdiction to have its own public prosecutors and judges. In effect, military officials have become the people who report the case, carry out the arrest, interrogate the suspects and prepare an investigation report to submit to the public prosecutors. This leaves little room for checks and balances and makes any effort to review the lawfulness of such investigations almost impossible. The post-coup criminal proceeding has become a major obstacle preventing people from access to justice, which is a breach of the rule of law and human rights. There are two recommendations on this issue.

2.1. Stop using the judicial process to legitimize the coup and recognize people’s rights and freedoms. An effort must be made to stop legitimizing the NCPO’s exercise of power and giving it legal precedence. The Court of Justice, the Administrative Court and the Constitutional Court should be allowed to adjudicate in order to guarantee the rights and freedoms of the people. These rights and freedoms warrant respect, protection and promotion as per Thailand’s international obligations.

2.2. Reform the criminal justice process i.e. by demilitarizing all levels of the criminal justice process; ensuring an accessible judiciary which allows the public to monitor how the court functions and keep it in check; improving the performance of personnel in the criminal justice process.

As to access to a fair criminal justice process, there are more specific recommendations at different stages of the process (i.e. the inquiry, indictment, trial, and enforcement of sentencing stages), as follows: (1) Stop arresting and holding individuals in custody in informal detention facilities or in military barracks, whether the arrest is made by military officials or officials from other government agencies. (2) Stop involving military officials and officials from other agencies in the processes of evidence corroboration and suspect interrogation. (3) Stop prosecuting individuals who fail to report themselves as requested by the NCPO Orders and stop prosecuting cases which clearly lack all elements of crime.

3. Remedies and compensation for victims of the exercise of state power during the 2014 coup

Human rights violations have been carried out concretely and extensively during the past few years. They can be divided into three categories: non-prosecutorial human rights violations; prosecutorial human rights violations through politically motivated charges; and the impacts of the enforcement of laws dating back to the 2014 coup. To address the needs of victims of the exercise of state power during the 2014 coup, the recommendations can be made two-fold, (1) toward concerned individuals and (2) concerning remediation and compensation for the damage.

Recommendations to concerned individuals

3.1. Three recommendations concerning remedies are proposed to all political parties contesting in the election and to the government post the 24 March 2019 election: (1) Compensation and remedies should be offered to those affected by human rights violations during the 2014 coup, particularly from 22 May 2014 to May 2018. (2) Rescind legal cases prosecuted as a result of the exercise of the right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. (3) Raise social awareness about the stigmatization of suspects of grave criminal offences even before they have the chance to prove their innocence in the justice process.

3.2. Recommendations to the government committed to reviewing the exercise of power during the 2014 coup

3.2.1. Put in place a mechanism to establish truth by setting up the “Inquiry Committee of the Patterns and Nature of the Exercise of State Power and the State of Human Rights during the 2014 coup”.

3.2.2. Survivors should have a role in determining details of the remedies and compensation, which could be made through various means including: the government offering a public apology; compensation and damages; psychological remedies; fair trials for cases stemming from the exercise of the right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly; a sustained effort to raise social awareness about the stigmatization of the survivors; an assurance of preventing any repetition of the offence. The government should consider societal remedies.

In addition, the powers that be must be brave enough to ensure perpetrators are held to account for their criminal offences. These can be divided into four categories including (1) an offence committed as a result of policymaking or planning by the upper echelons of government, (2) an offence resulting from ordering the commission of offences further down the chain of command, (3) an offence resulting from committing a human rights violation, and (4) an offence resulting from aiding and abetting the commission of an offence against rights and freedoms.

How to remediate and compensate for the damage

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) divides “injured parties” into three groups: (1) individuals or a group of individuals/organizations whose rights have been violated, (2) families, or those living under the custodianship of an injured party, or individuals who are beloved persons to an injured party, and (3) individuals or organizations offering help to the injured parties and who, as a result of which, may have been subject to a rights violation themselves. There should be an “Inquiry Committee to Review the Patterns and Methods of the Exercise of Power and the State of Human Rights during the 2014 Coup”. This Committee would be tasked to explore the “patterns and nature of the exercise of power by the NCPO and government officials during the 2014 coup”; to categorize the damage; to classify the damage; to determine the number of injured parties with collaboration from representatives of the injured parties through formal and informal meetings; to investigate the roles of individuals or organizations involved in the commission of the rights violations; to retain any incriminating evidence which can be used in the justice process; etc.

4. Management of the NCPO Announcements and Orders, other laws decreed by the NCPO, and court judgments

Under the rule of the NCPO, the mechanisms and legal system they have created have significantly hampered the rule of law, instead creating a country under rule by law. The rule of law was essentially dismantled the day the coup was committed. It has rendered uncertain the status of individuals and their fundamental rights. The lack of checks and balances in the legislative and executive systems has led to the arbitrary exercise of power and enabled impunity.

This mechanism of governance manifests itself through legal and political institutions including the 2007 Constitution, 132 NCPO Announcements NCPO, 214 NCPO Orders, 207 Head of the NCPO Orders issued by virtue of Section 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution, and at least 444 other laws enacted by the National Legislative Assembly (NLA). These Announcements and Orders will remain as exceptional additions to the legal system unless they are repealed. The fallout of the NCPO’s rule will continue even after it ceases to exist. The Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) propose the following recommendations to review the remnant laws and judgments:

4.1. Amendments to the 2007 Constitution. There are two recommendations here: (1) It is imperative to first amend Sections 255 and 256 which prescribe the amendment procedure. (2) Repeal Sections 265 and 279, which legitimize the acts of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) and the lawfulness of all the NCPO Announcements, NCPO Orders and Head of the NCPO Orders, as prescribed in Sections 44, 47 and 48 of the 2014 Interim Constitution.

4.2. Dealing with legislations enacted by the National Legislative Assembly (NLA). These laws can be divided into three groups: (1) laws bearing gross impacts on rights and freedoms, (2) laws that provide for significant changes in state structure and (3) laws concerning general public administration.

4.3. Dealing with NCPO Announcements, NCPO Orders and the Head of the NCPO Orders. These decrees can be divided into two groups: (1) Decrees issued to crack down on political dissent and perpetuate human rights violations, and (2) Decrees involving general public administration.

4.4. Dealing with laws that violate human rights by reviewing their legal elements and the punishments accorded to each offence. As several laws have been enacted purely to suppress the exercise of the right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, they must be amended to ensure their compliance with human rights. Any restriction of individuals’ rights must be done proportionately and only as necessary in a democratic system.

4.5. Dealing with court judgments. This can be divided into two groups based on the judgment outcomes, as follows:

Group 1: Judgments which legitimize and validate the commission of the coup by the NCPO; Group 2: Judgments which offer the NCPO and their personnel immunity from criminal liability; and Group 3: judgments made to punish the people based on laws that violate rights and freedoms.

None of these recommendations may be realized without the majority of the people recognizing the values of democracy, rule of law and human rights.

Their realization may therefore have to start by having at least 50,000 eligible voters sign a proposition to amend the Constitution, including the repeal of Section 279, which shields the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). Even after the NCPO ceases to exist, the effects of the coup will remain impactful and an effort must be made to repeal or amend certain laws in compliance with due democratic process.