Although the coronation ceremony of King Rama X from 4 to 6 May 2019 and the royal celebration from 22 to 28 May 2019 took place “peacefully”, violations of personal freedom through constant monitoring and intimidation by state authorities occurred in secret throughout the course of the events. They gained little media coverage.

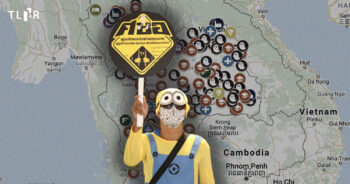

In the past month, state authorities from different sectors, including the police, military, and special branch police, have closely monitored people categorized as “target groups” or “monitor groups” to track their movements and restrict their political activities during the coronation period. From early April to mid-May 2019, the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights received at least 38 reports of monitoring and intimidation cases by state authorities in various areas, with the number of people being harassed totalling 27.

Among these were former suspects and detainees in offences related to the monarchy, including Article 112; a group of people who had been prosecuted or had made statements about the Thai Federation; former detainees in cases related to weapons; and others.

Furthermore, it has been reported that a group of activists has been harassed. These include activists who called for an election, artists who produced work criticizing the NCPO, former political bookmakers, etc. This means the groups of people being monitored during this period were quite diverse, as they had not necessarily previously expressed anything about the monarchy.

House Visit by Authorities to Inquire about Activities

Reports about monitoring and intimidation by state authorities in relation to the coronation started to surface as early as before the Songkran festival and peaked in frequency in early May, as the ceremony drew near. Even after the ceremony, there were still reports of state authorities monitoring and inquiring about citizen’s activities. The authorities in question comprised special branch polices or local police officers in plain clothes, military officers both in uniform and plain clothes and officers from other security-related departments.

The most common type of intimidation and monitoring by the authorities was a house visit to inquire about individuals’ travel plans, focusing on the coronation period. The authorities asked whether they would travel during the ceremony or whether they planned any activities. They also asked to take photos to report to their supervisors. The authorities didn’t usually provide their name or department, stating only that they were from the police or military. In most cases people had not been given advance notice of the visit.

Many were warned by the authorities not to do anything during the coronation period. Some were threatened by the police and told that if they did not comply, they would be handed over to the military and that the military might “abduct” them. In some cases, if the wanted person was not home the authorities talked to his/her family member instead.

A Constant Weekly Monitoring of the Target Group

Among the groups of people that have been “watched”, authorities have continuously monitored many of them almost every week from mid-April until after the ceremony.

One example is the case of a resort owner in Kampaeng Phet province, who had participated in a gathering against economic problems and was prosecuted on grounds of political gathering. She was also detained at a military camp during the “Un Ai Rak” bicycle ride event in December 2018 as she was accused of possessing black t-shirts from the Thai Federation group. Three plainclothes military officers visited her after the Songkran festival to ask if she had any activities planned during the approaching coronation ceremony and discuss economic problems with her.

In the last week of April, two uniformed police officers and one military police officer came to see her again. They drove a military car to her resort, which caused panic among the customers. The authorities briefly asked how she was and what she was doing and then they left.

During the coronation ceremony, she travelled overseas and found out that officers of an unknown background visited her son and close family members to verify whether or not she really had left the country and when and to where she would return.

On the day of her return on 8th May 2019, she was met by special branch polices. They explained to her that they had to follow her because they feared she would join an activity. They also asked to take a photo of her to report to their “boss”, but she refused. The monitoring activities by the authorities persisted, even when she repeatedly insisted that she had no plan to organize or join any activities.

Monitoring to Demand a Regular Report of Individuals’ Movements to the Authorities

A former prisoner of an Article 112 case revealed that she was continuously monitored by state authorities from April until early May. After the Songkran festival, three special branch polices went to her provincial home and talked to her family. They asked her family members about her, what kind of job she had, where she lived, and whether she had permanent residency. They also showed the family that they had already gathered some information from her Facebook page. The authorities also told the family that the state was concerned that she might cause “disorder” during the ceremony, and therefore asked the family to control her behaviour. Before they left, they asked to take photos of the family from different angles so that they would not have to return multiple times, and finally asked for the former prisoner’s phone number.

On 24th April 2019, a police officer called this individual on the phone and tried to get her address in Bangkok. He insisted that he wanted to meet her to talk because he had some concerns about her plans during the coming ceremony. When she informed him that she had some errands to do at a government office on the next day, the police officer said he would go see her there and asked her to notify him when she arrived. However, when she did so the next day, no one came to meet her.

Four days later, another police officer contacted her and informed her that the security sector had specifically assigned him to follow her and that she could ignore the other officers who had previously contacted her. He asked for information about her workplace and asked her to check in with him on a regular basis, not to turn her mobile phone off, and not to go anywhere without notifying him as she might be at risk of “abduction.” He also strictly prohibited her from entering the ceremony area until it was over. The officer claimed that he did not want to restrict her freedom but asked for her cooperation during this time.

In the meantime, another former prisoner of an Article 112 case informed us that police officers of an unknown affiliation travelled to his hometown in Northeast Thailand and asked the village headman to bring him to the individual’s house. There, they met with his older sister and claimed that they wanted to assist him in his case, even though it had already been closed. The real intention was therefore unclear. The police officers also asked his sister about his occupation and address in Bangkok.

This former political prisoner stated that he had previously been followed by state authorities but had never before received a visit to his provincial home. The authorities had previously come to see him directly in Bangkok, as they already knew his address. The real purpose of this house visit was therefore unknown.

Monitoring of People Not Directly Involved in Monarchy Issues

Another case concerned a former editor of a political magazine many years ago, who had not been involved in any political activities. However, in the month of April before the Songkran festival, two special branch polices in plain clothes went to his residence and asked to talk. They explained that the authorities had some concerns about possible statements during the coronation ceremony and asked him to refrain from any activities. Likewise, they asked to take photos of him to report to the “boss.”

On 3rd May, two special branch polices came to see him again. They asked similar questions about what he was doing, asked him to refrain from any activities during the ceremony, and asked to take photos.

An artist, who used to produce political cartoons mocking the junta’s use of power but never the monarchy, was visited by two plainclothes authorities of an unknown affiliation one day before the ceremony, on 3rd May 2019. They asked if he had anything planned for the ceremony and what he intended to do on those days. They also asked if he was in the same group as certain activists. He answered no to both questions. The authorities also showed him a document containing pictures of individuals on their monitoring list, including himself. He noticed that there were pictures of many other people, but he did not know any of them.

House Watch during the Ceremony

During the ceremony, the monitoring activities continued with vigour, especially via telephone calls. Additionally, some activists have had their houses closely watched by authorities 24 hours a day. A case in point is Somyot Pruksakasemsuk, a former Article 112 prisoner, whose residency area was monitored by both police and military officers during the coronation period. Consequently, he had to cancel all appointments between 4th and 7th May 2019 and decided not to leave the house at all.

In the case of Ekachai Hongkangwan, on 5th May 2019 the police took him to the cinema in order to keep a close watch on him all day.

As far as the report revealed, this kind of 24-hour monitoring activity by the authorities during the coronation period also happened to at least three other activists. There have also been some cases where the authorities asked people to take a picture of themselves and send them to them, and to report their location and what they were doing.

Additional Arrests in Cases related to the Thai Federation

Last April, authorities arrested and prosecuted two more people related to the Thai Federation group. One of them was Mr. Thoedsak (undisclosed surname), a driver for a private company, whom the police officers detained with an arrest warrant at his workplace in Phuket on 2nd April 2019. They then brought him to Bangkok and charged him under Article 116 (sedition) and Article 209 (forming a secret society) of the Thai Criminal Code. The allegation stemmed from the fact that Mr. Thoedsak was wearing a black shirt near McDonald’s, The Mall Bangkapi Branch, on 5th December 2018. The day after, Mr. Thoedsak, who was already detained, was taken to interrogations at a police station and a military camp. He was later released without charges.

Another case is that of Ranee (undisclosed surname), who was arrested during her son’s graduation ceremony on 11th April 2019. She was accused of the same offence as Mr. Thoedsak: wearing a black t-shirt that bore no Thai Federation symbol. She was walking in Central Ramintra shopping mall when the plainclothes police officers approached her. Although she refused to go with them, she was followed to her house. At that time, they did not press charges. However, four months later, an arrest warrant was issued and she was arrested and prosecuted.

Witch-hunting of Internet Users

In addition to the monitoring activities by state authorities during the coronation ceremony, the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights has also discovered cases of “witch-hunting.” Some political internet pages encouraged their users to track people who posted their opinions about the coronation online. Their names and personal details were disclosed. It was reported that an internet user in a southern province was tracked down and reported to state authorities. Consequently, a special branch police went to see this internet user and forced him/her to post a video clip apologizing for his/her political posts.

Another case involves a political page that took an image of a political activist and edited it with monarchy-related content, and accused him/her of being an anti-royalist, even though this was not true.

These are just a few examples of incidents that have occurred in the past month. Behind the curtain of the grand coronation ceremony lie stories of harassment of individuals, most of whom had no activities planned. Their previous records of having expressed their opinions or participated in political gatherings were all that led them to be monitored by the authorities during this period.

This abuse of power continues today. Although a general election has been held and the opening meeting of the new parliament convened, these violations show no signs of stopping.